The Grazing Revolution

Table of Contents

About the book

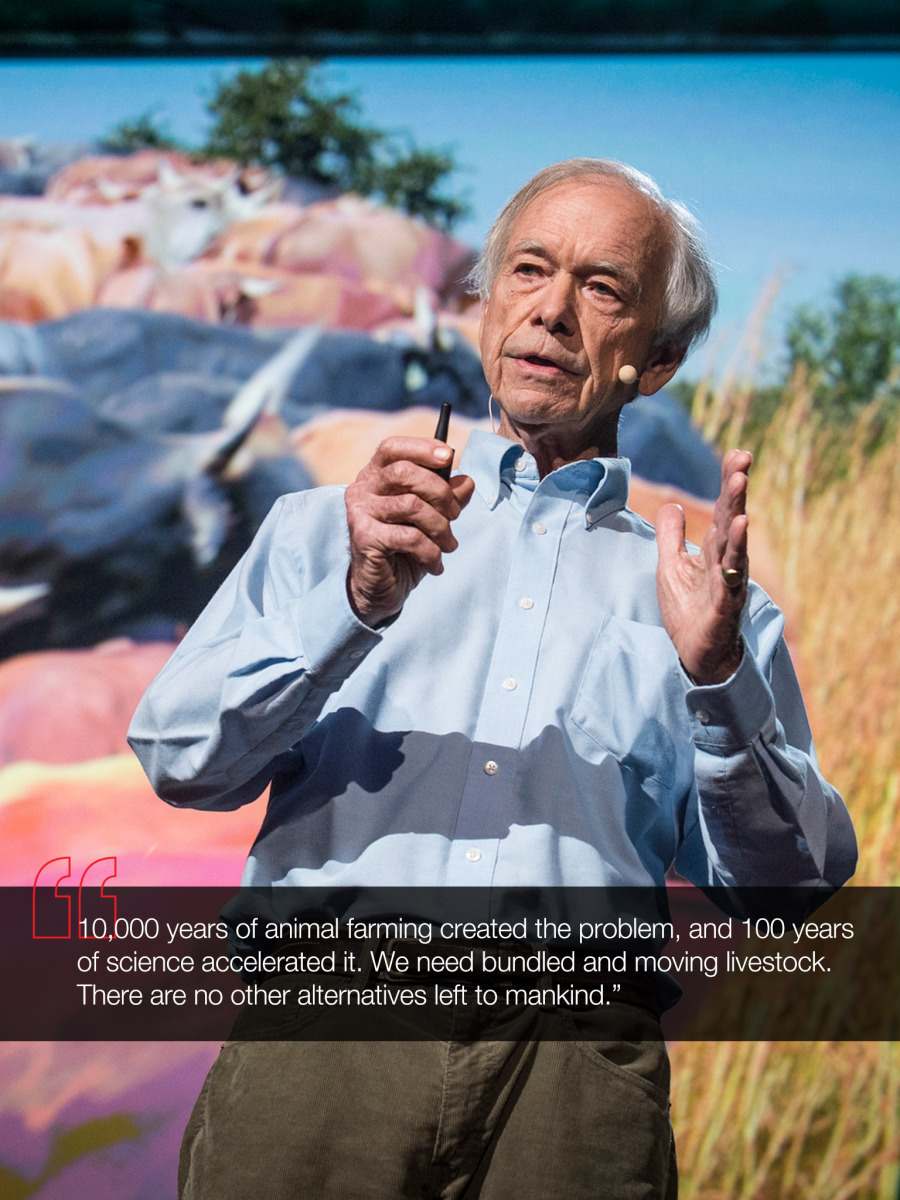

This book is a companion piece toAllan Savory's TED Talk, delivered in February 2013 in LongBeach, Calif.

Watch Allan Savory's talk on TED.com.

allan-1378745757-52.png

allan-1378745757-52.png

Preface

Today, a perfect storm is bearing down onus. It owes its genesis to a trifecta of factors that isoverwhelming humanitys options for a viable future: Our globalpopulation, having surpassed 7 billion, is rising exponentially; onevery continent outside the polar regions, a process known asdesertification is destroying the land supporting that population;and Earths climate is changing considerably faster than thescientific community had anticipated.1

Our society believes that some form of technology will fixclimate change, which we typically attribute to greenhouse gasesemitted from burning fossil fuels. Certainly technology can providebenign sources of energy to replace fossil fuels. But it will takemore than just clean energy to tackle climate change. Ouragricultural practices how we produce and manage the crops andlivestock that sustain us are, I believe, equally to blame.Specifically, these practices having already destroyed many pastcivilizations are largely responsible for the desertificationunderway around the planet. One statistic bears this out: Eachyear, the earth loses (to erosion) 75 billion tons of soil, mostlyfrom agricultural land,2which amounts to 10 tons for every human alive today. More alarmingis the advancing rate of soil loss, which leads directly todesertification. And according to mounting scientific evidence, itappears that desertification itself is a major contributor to andnot merely a symptom of climate change.

To give you an idea of the scale at which desertification isoccurring, look at this view of the world, courtesy of NASA:

NASA

NASA

Generally, dark green land is not turning to desert, while thefringes of green outside the high latitudes and the brown aredesertifying, even when rainfall is high. Keep in mind that thebrown areas also encompass natural deserts, such as the Namib inSouthern Africa and the Gobi of northern China, which get almost norain at all, as well as parts of the Sahara. Over millennia thesedeserts have been expanding into grasslands and savannas, resultingin failed civilizations. The deep black soils and abundant wildlifeof Libya, described in the fifth century B.C. by the Greekhistorian Herodotus, are now part of the Sahara. The greatcivilizations of the Middle East the Phoenicians, Persians, the100 Dead Cities of Syria all succumbed to desertification, as didthe empires of northern China.3

Human-induced desertification happens when land becomesincreasingly dry despite no change in rainfall. Rivers that onceflowed year-round run only during periods of heavy precipitationand then quickly dry up. Silt and eroded soil fill dams untiltheyre no longer capable of storing water. Aquifers are notreplenished and water tables drop. Crop yields shrink. Grass andforage for animals, wild and domestic, becomes increasingly sparse.As a result, people who make their living from the land becomeimpoverished. Unremitting poverty leads to social breakdown. Abuseof women and children rises, along with violence, as humans competefor scarce resources and access to land and water. The affectedpeople forsake the land and swarm into cities or emigrate to othercountries, creating a host of other social and economicproblems.

The large area of brown on the NASA image from North Africa,through the Middle East, across the former Soviet republics toChina and into Pakistan and India are suffering the symptoms ofdesertification. It is no surprise that these regions are the mostvolatile, violent, and unstable in the world. Desertification isequally severe over large swaths of the western United States,Mexico, Argentina, Chile, and Australia. It wont be long beforenations are fighting wars over water wars that will likely begreater and more violent than any fought over oil.

This vast environmental change began tens of thousands of yearsago, when humans became predators. Research shows that humans hadonce been more akin to omnivorous scavengers, on equal footing withmost other species. But when hominids mastered fire, evolvedlanguage and organizing skills, and developed weapons such as thespear, they became formidable predators. This was particularly thecase in the grasslands where their prey ran in herds grasslandswhose deep, rich, water and carbon holding soils had developed overmillions of years thanks to a balance of grazing animals, thepredators that fed on them, and infrequent lightning-sparked fires(commonly associated with rain).

Predators hunting in large packs had to isolate a single animalin order to kill it, but humans could now wipe out entire herds ofanimals. They drove the herds over cliffs and into bogs, or usedfire to corral and then slaughter them en masse. With this newfoundadvantage, humans began changing the environment around themdrastically. Too few animals remained to graze on and therebyspur the replenishment of grasses and plants, resulting in deadvegetation instead.

As the work of Tim Flannery has brilliantly explored inAustralia, early humans across the globe used fire to eliminatethis rank vegetation and bring on a flush of new grass to attracttheir preferred prey. They also used this method to provide greenfeed for livestock, which humans domesticated around 12,000 yearsago. All of my research supports Flannerys assertion that suchburning can expose soil in a way that makes it easily carried awayby rain and wind. Without grass and soil covering litter to retainit, residual moisture quickly evaporates. The world had never knownfire in such frequency and expanse. And in the millennia thatfollowed, vast human-made deserts formed and spread.

Early humans blamed desertification on livestock. They believedthat livestock numbers were too high and this resulted in theirovergrazing grasslands, leading to desertification. This convictionso permeated society that it assumed scientific validity andremained the explanation for desertification for more than twocenturies. Nobody questioned this explanation until recently.Its now time to examine the antiquated roots of these beliefs tosee where the truth lies.

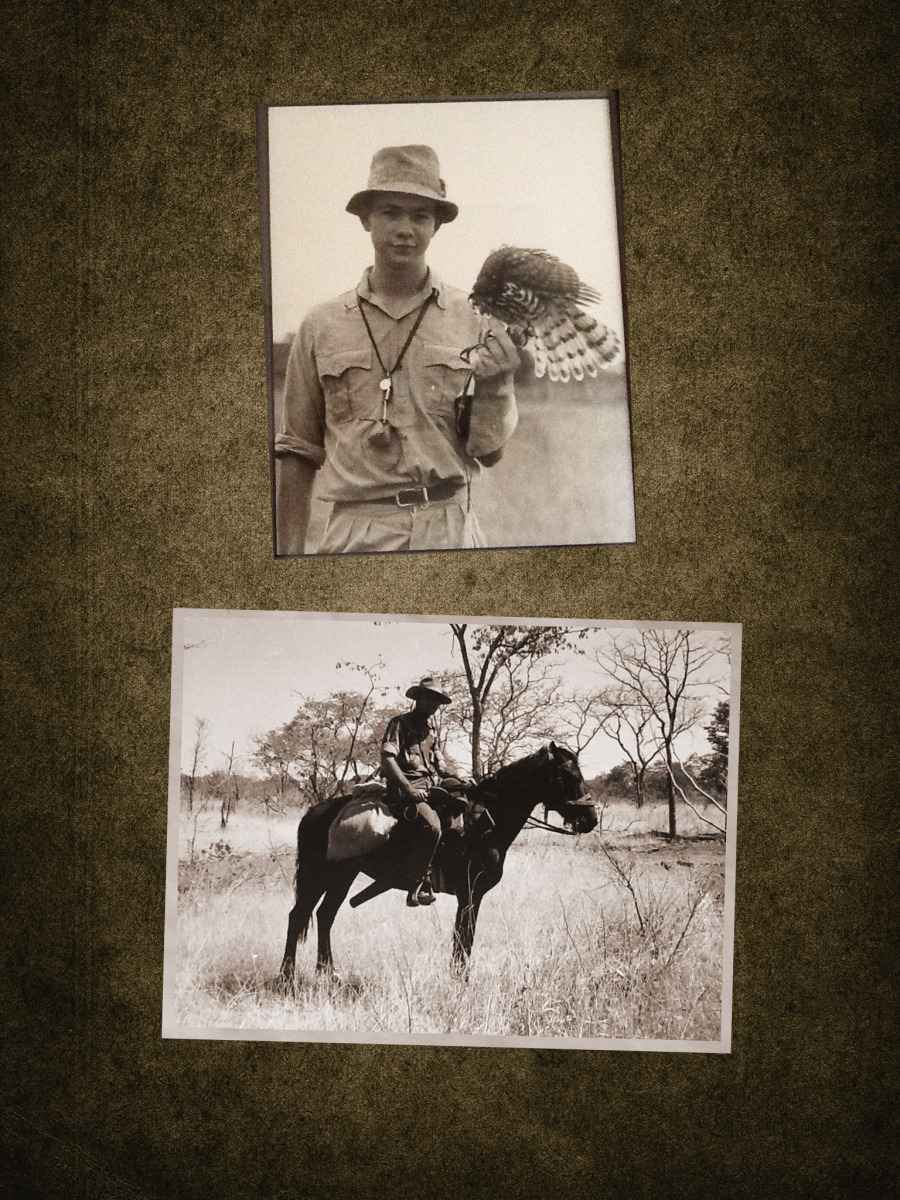

Allan Savory, in his late teens,holds a hawk he is training. Years later, he traverses the land onhorseback while game ranching.

A radical idea

The roots of my interest in landpreservation began in early childhood. I was born in 1935, inBulawayo, Zimbabwe (what was then Southern Rhodesia), and grew upwith a civil engineer father whose dream was to construct theworlds first mega-dam (which he ultimately had a hand in). Whenbuilding roads, he went to extreme lengths to ensure they werescenic: Rather than felling an old tree or blasting through a largeboulder, hed route around them. I spent weekends as his schoolboyassistant helping survey dam sites in environmentally sensitiveareas, something he would not entrust to his staff. We wanted toensure these sites remained beautiful. And we spent long days inZimbabwes Wankie Game Reserve, now a famous national park, whereacross vast tracts of arid land my father built dams to providewater for wildlife. My father made it impossible not to love thebush and by the time I left high school, I could not imaginespending my life anywhere else.

allan-1378745757-52.png

allan-1378745757-52.png NASA

NASA