30-SECOND

ECOLOGY

50 KEY CONCEPTS AND CHALLENGES, EACH EXPLAINED IN HALF A MINUTE

Editors

Mark Fellowes

Becky Thomas

Contributors

Heather Campbell

James Cook

Julia Cooke

Stephen Murphy

Sarah Papworth

Adam Smith

Illustrator

Nicky Ackland-Snow

INTRODUCTION

Mark Fellowes & Becky Thomas

All organisms interact with others and with their physical environment. The study of the causes and consequences of these interactions lies at the heart of ecology, which addresses questions about these interactions from a molecular to a global scale. Ecology has always addressed fundamental questions such as why the tropics are so diverse and why birds lay a certain number of eggs but today, many critical threats are in immediate need of answering. How do we slow down biodiversity loss, how do we mitigate the environmental effects of climate change, how do we protect people from vector-borne diseases? Ecology works to answer these questions too.

Early ecologists did not have such concerns. Ecology as a science emerged from the great naturalist-explorers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Luminaries such as Alexander von Humboldt, Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace travelled the globe, collecting specimens. Their experiences, alongside many others, shed light on the origins of species, the behaviour of these species and the great global patterns of biodiversity. The term ecology (from Greek, meaning the study of where things live) was coined in 1866 by Ernst Haeckel, a German zoologist. By the early twentieth century, ecology had become a hypothesisdriven science, with early work examining topics such as the structure of food webs and the mathematics of predatorprey interactions. From those early beginnings, ecology grew into a fundamental science, but, nevertheless, often with an applied perspective.

In the 1960s, ecology became more radical. Rachel Carsons Silent Spring was a clarion call against the threat of environmental degradation, and social action organizations such as Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth brought environmentalism to a worldwide audience. Ecological science underpinned many of their perspectives, but also challenged many assumptions. Ecology began to influence how we viewed the world.

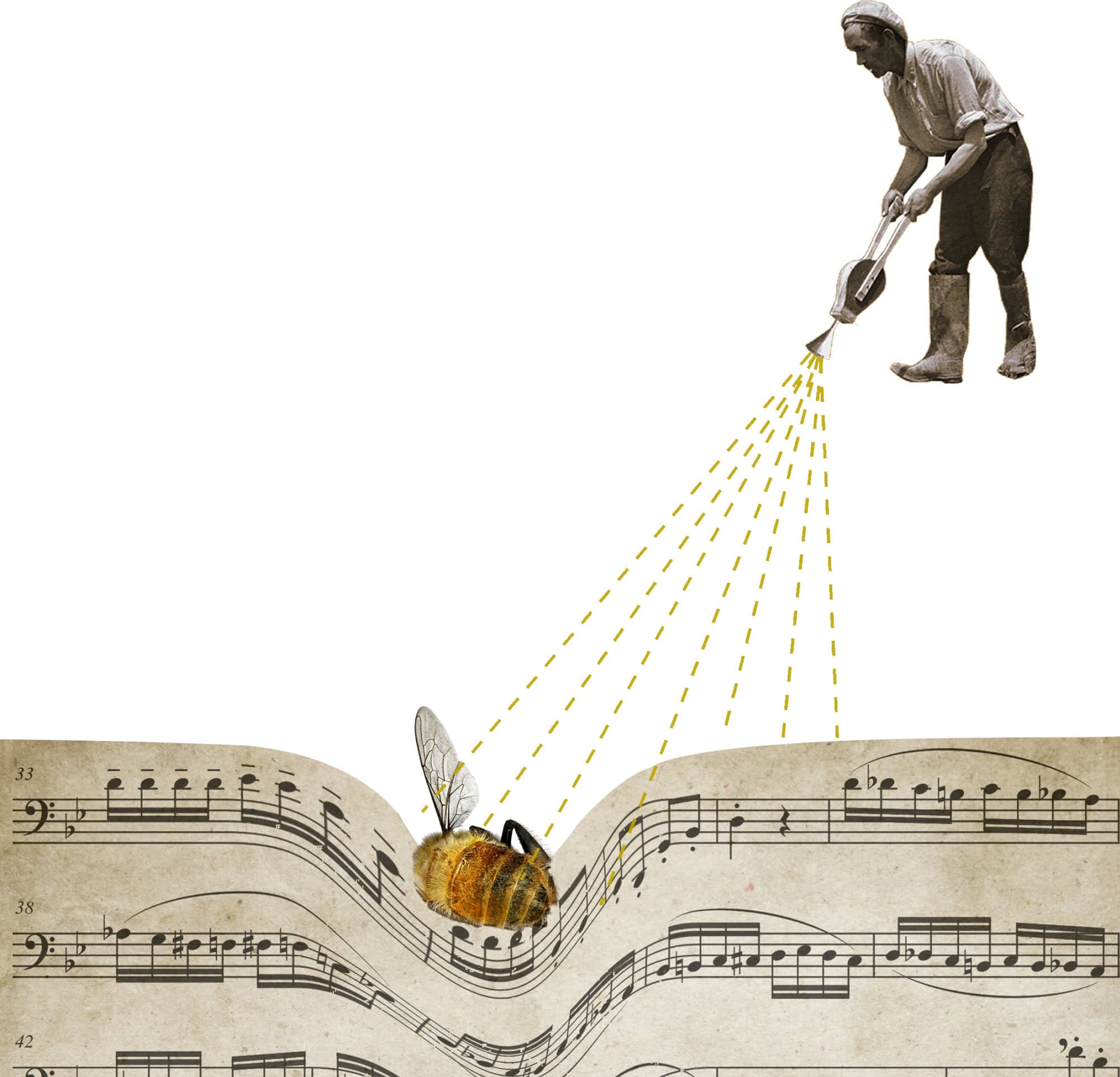

Humankinds desire to control often has unintended consequences, such as using insecticide to protect crops. Insecticides unintentionally harm pollinators, without which many crops would fail.

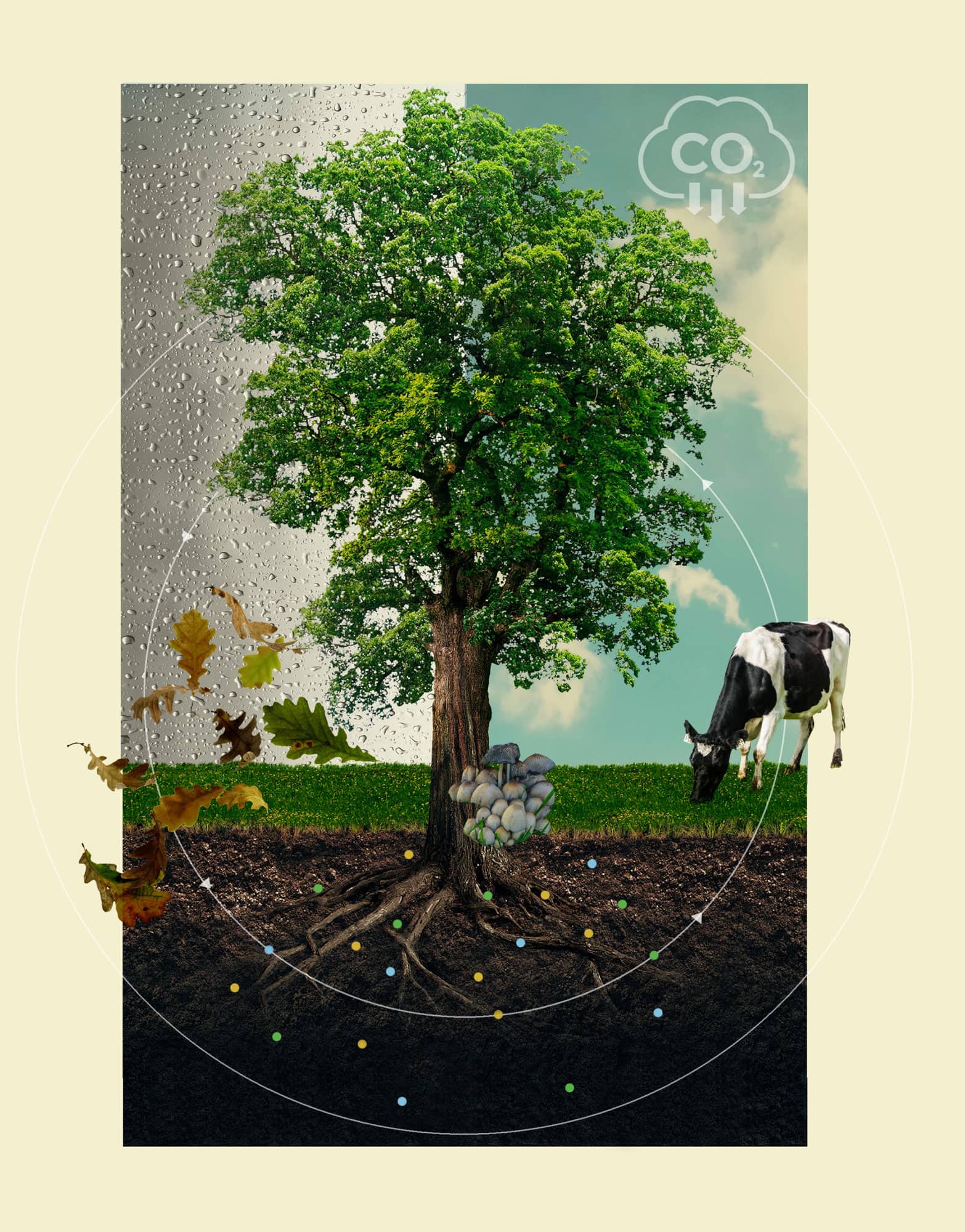

Today we live in the Anthropocene. The influence of humankind on the planet has reached a point where even if we were to all disappear tomorrow, the signs of our presence will remain for millions of years. There is no corner of the Earth that we have not altered. The composition of the atmosphere has been altered by the gasses we release into the air, causing global climate change, acid rain and pollution. We have razed forests for agriculture and forest products, we have removed a vast proportion of fish from the seas and plastics litter the ocean depths, and we have covered the land with concrete for our homes, roads and workplaces. The human population is growing exponentially. Each year, we now add the equivalent of the combined populations of the UK and the Netherlands to the global human population.

The outcomes are habitat degradation and species loss. Many argue that we are in the midst of the sixth great extinction, with the fifth being that which occurred when the dinosaurs were wiped out by a meteor slamming into the Yucatn Peninsula 65 million years ago.

Protecting nature and natures services will be an increasingly difficult challenge, but there is little choice other than to act now. Ecology helps us do that. Ecology links nature, people and planet in a single subject, seeking to understand the fundamentals of why nature works the way it does, and then taking that understanding and applying it to pressing problems in conservation, habitat management, natural resource use and agriculture. Humans do not exist outside of nature, although insulated homes and air-conditioned offices may suggest otherwise. Humans are an integral part of the global ecosphere, and understanding what that means is more important today than ever before.

This book introduces the main concepts in ecology. Starting with an introduction to Evolution & Ecology, it explores how these two principles are closely linked. In many ways, ecology can be thought of as natural selection in action. Behavioural Ecology examines how the adaptive behaviour of species affects their ecological interactions. Population Ecology is concerned with the population dynamics of species, an outcome of behaviour. Here, we consider how population size is affected by competition for resources from enemies and also by the need to disperse. Together, populations form communities, and the chapter Communities & Landscapes moves up in scale to examine why ecosystems are so complex, how energy flows through systems and why some species have much more influence on their neighbours than others. Together, communities and the physical environment lead to the formation of biomes, and in the next chapter, Biomes & Their Biodiversity, those habitats and species that share common themes and are found around the world are examined including grasslands, forest and tundra, all of which drive global patterns of biodiversity.

Applied Ecology changes course to consider how this fundamental underpinning can help solve global problems. Here youll find examples of how ecology can help maintain biodiversity and sustainably feed the worlds people. Finally, Ecology in a Changing World ends with some of the greatest challenges ecologists currently face, with the emergence of issues such as urbanization and global climate change demanding rapid, radical answers.

Forests are dynamic systems that constantly change through decay and regrowth.

EVOLUTION & ECOLOGY

EVOLUTION & ECOLOGY

GLOSSARY

allopatric speciation The splitting of one species into two due to geographic separation of different populations so that they no longer interbreed and evolve to be different.

asexual reproduction Occurs when offspring arise from a single parent and thus receive genes from only one individual. It is the main form of reproduction in many microbes, such as bacteria, and also occurs alongside sexual reproduction in many plants and fungi.