Basque Series Editor: William A. Douglass

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

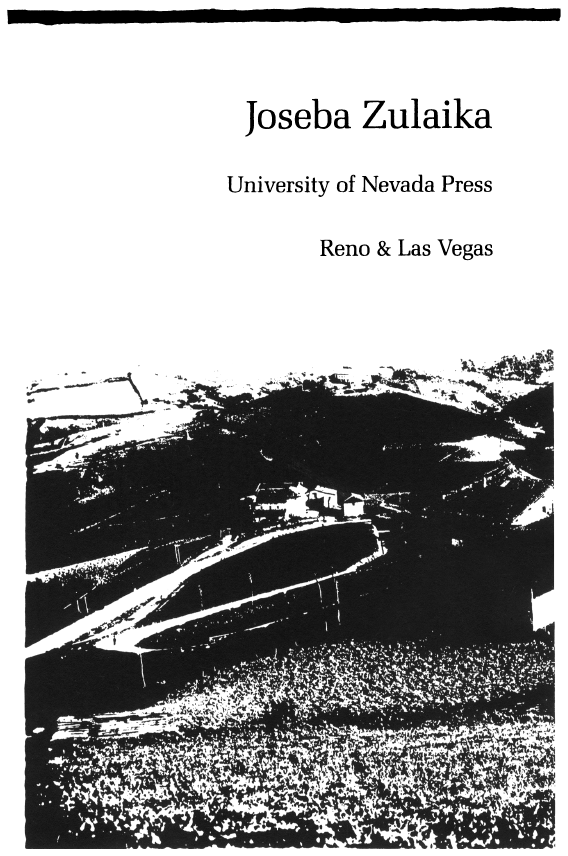

Zulaika, Joseba.

Basque violence : metaphor and sacrament / Joseba Zulaika.

p. cm.(Basque series)

Based on the authors thesis (Ph.D.)Princeton University, 1982.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-87417-363-5 (alk. paper)

1. ViolenceSpain. 2. BasquesSocial conditions. I. Title. II. Series.

HN590.Z9V59 1988

303.620946dc 19

87-35432

CIP

University of Nevada Press

Reno, Nevada 89557 USA

www.unpress.nevada.edu

Copyright Joseba Zulaika 1988

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Designed by Richard Hendel

This book has been reproduced as a digital reprint.

ISBN-13: 978-0-87417-532-5 (ebook)

Acknowledgments

The people presently living in Itziar are my argumenti personae. With their consent I have not tried to hide their biographies nor have I changed their proper names. Unless otherwise noted, all conversations quoted in the text took place during my fieldwork (19791981) and all translations are my own. At moments I have imagined this ethnography of Itziar as a Homeric tragedy of which I am the narrator but which is acted out in real life by the community of villagers, myself included. In a substantive sense this work is a collective creation by Itziars villagers, the live protagonists of this book, which is dedicated to them.

During the years I devoted to writing this book I contracted debts with many people. The book is based on a doctoral dissertation submitted in 1982 at Princeton University, where faculty and graduate students of the anthropology department made my years of study most stimulating and enjoyable. Lisa Harrison shared with me the initial stage of the writing. Professors David Crabb, Tefilo Ruiz, Gananath Obeyesekere, and Rena Lederman read the first drafts of some chapters and made important suggestions. The assistance I received at the Basque Studies Program at the University of Nevada, Reno, from anthropologist William Douglass, linguist William Jacobsen, bibliographer Jon Bilbao, and folklorist Sven Liljeblad was invaluable. Professor Hildred Geertz provided a detailed and perceptive commentary on the strengths and weaknesses of my dissertation. I owe the greatest debt to my mentor, Professor James Fernandez, who during my graduate years took attentive intellectual care of my work. They all have my lasting gratitude and affection.

In the final writing I was aided immensely by William Douglass, who extensively edited the whole of the book at various stages and provided substantial suggestions regarding form and content. I am indeed fortunate to have been assisted by someone who combines an in-depth knowledge of Basque society with long-tested editorial skills and who is also a dear friend. He has rewritten entire paragraphs with the same care he would give to a book of his own, and at times I felt he was more faithful than I was to the way Basques experience political violence, even if that meant wrestling with and cutting down passages that had become almost sacred to me. Robert Clark read the completed manuscript and made pertinent observations, which I have incorporated. Critical remarks by Peter Loizos and an anonymous reviewer were helpful. I have also profited from Don Julio Caro Barojas comments on this work and from comments by my colleagues Jess Azcona, Teresa del Valle, Joxe Azurmendi, and the students of symbolic anthropology at the Basque University. Koldo Larraaga, William Christian, Sandra Ott, Mara Ctedra, Carmelo Urza, Mateo Osa, and Mikel Azurmendi read parts of the manuscript and suggested corrections. I am grateful to them all. None of them shares responsibility for any inadequacy in this book. I owe special thanks to Kate Harrie for her careful editing.

The fieldwork on which this study is based was made possible by the financial support of the Department of Anthropology of Princeton University, a grant from the National Science Foundation, and three summer grants from the Comit Hispano-Americano. A postdoctoral grant from the Basque Studies Program at the University of Nevada, Reno, was decisive in converting the dissertation into a book. The chapter on ritual action is the initial result of a longer project on ritual models of causation underlying Basque violence, which was financed by the H. F. Guggenheim Foundation. I am indebted to them for their generous support.

During my fieldwork I was helped by many people. I am particularly indebted to the families of Menpe and Mantxuene, who housed me for a summer, when I was in the Viscayan town of Mendata. In Itziar not only was I assisted by everyone in one way or another but also frequently confronted in my views and queried as to what should be done to resolve a given problem. I owe much to my own family, who had to put up with my presence and my questions for long periods: my late mother provided much sociological information on the older generations of Lastur and Itziar, and during the writing phase my father wrote me several letters in response to my queries.

Through this work I came to better know and appreciate many of my fellow villagers, who shared with me their friendship and life experiences. The protagonism I have conferred on some people over others reflects only my own subjective selection for the purposes of the plot of the book. The only person who, of necessity, acquires an unduly prominent role is the writer himself. Just as the events narrated here, including heroic action and ritual killing, are constructed collectively by the community of Itziar, so is this book a collective creation aesthetically reflecting the living experience in which all we villagers are participants.

Prologue

Return to Itziar

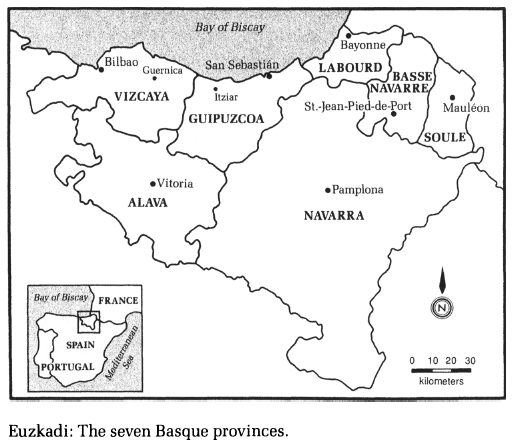

In the summer of 1979 I returned to Itziar to do fieldwork on Basque political violence. Itziar is a small village of peasants and factory workers on the Cantabrian coast in the province of Guipzcoa (Spain). I was born in Itziar-Lastur in 1948 and spent my childhood there. Since I was twelve years old I have lived away from the community, attending seminaries and colleges. When I went back in 1979 I was a philosophy licentiate and had studied anthropology for four years at Memorial University (Canada) and Princeton University, where I was a doctoral candidate. Now I was again living in my natal village, where I hoped to immerse myself in local affairs. This was my anthropological jungle; I had returned to Itziar as both native and observer.

Between 1975 and 1980, Itziar, a village of about one thousand people, was shaken by six political murders. The armed group ETA (Euskadi Ta Askatasuna [Euskadi and Freedom]) was responsible for killing two police informers from Itziar and a civil guard married to an Itziar woman and resident in the village. An industrialist kidnapped by four ETA youths from Itziar was murdered in the village after the negotiations for his ransom between ETA and his family failed. A politically uninvolved worker married to a woman from Itziar and popular there, though residing and working in the next village, was killed mistakenly by ETA, which confused him with an alleged police informer. The civil guards killed an ETA operative from Itziar in the nearby town of Orio.