Insectpedia

Text copyright 2022 by Eric R. Eaton

Illustrations copyright 2022 by Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press is committed to the protection of copyright and the intellectual property our authors entrust to us. Copyright promotes the progress and integrity of knowledge. Thank you for supporting free speech and the global exchange of ideas by purchasing an authorized edition of this book. If you wish to reproduce or distribute any part of it in any form, please obtain permission.

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to permissions@press.princeton.edu

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

99 Banbury Road, Oxford OX2 6JX

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-21034-6

ISBN (e-book) 978-0-691-23663-6

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Robert Kirk and Abigail Johnson

Production Editorial: Mark Bellis

Text and Cover Design: Chris Ferrante

Production: Steve Sears

Publicity: Matthew Taylor and Caitlyn Robson

Copyeditor: Lucinda Treadwell

Cover, endpaper, and text illustrations by Amy Jean Porter

This book has been composed in Plantin, Futura, and Windsor

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in China

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Preface

This book is positively biased. Countless other books, plus magazine articles, advertising, videos, and social media memes demand we fear and exterminate insects. Insectpedia aims to refute those fears and ignite an appreciation of insects and those who study them. Even species for which we hold the most contempt, like tsetse flies, have redeeming qualities that will be illuminated here. Along the way, major principles of entomology will sneak in between the entertaining stories, and biographies of entomologists.

Insects are proof that evolution and instinct trump intelligence. We are overwhelmed by their sheer numbers, and forever a step behind in our efforts to subdue their impact on our health, agriculture, and wealth. They exploit our every weakness with maddening efficiency. Our relationship to insects has never been strictly adversarial, but it seldom serves the interests of business and industry to remember that. Do we turn some species into villains in order to turn a profit? That is less a conspiracy theory and more a shrewd business plan and marketing strategy.

Above all, we view insects as competitors for our resources. Pest is how we describe any species that we perceive as infringing on our property, person, or profits. Nature does not recognize the concept of ownership. Remarkably, natural ecosystems are seldom as chaotic as the artificial ones we create. There is no question that insects cause human misery and mortality directly, through the transmission of microbes that cause fatal diseases. Is it necessary, however, to eradicate the vectors? Billions are spent in campaigns to fog mosquitoes into oblivion, yet these are exercises in futility. In the United States, municipal spraying programs are driven by liability: the fear of lawsuits should citizens contract a disease and the city did nothing to prevent it.

Then there are murder hornets, Spotted Lanternfly, and other pests that we have manufactured through accidental or intentional transport to foreign lands. This appears to be an acceptable price to pay for unfettered global commerce, our insatiable thirst for exotic landscape plants and cheap products, all packaged in containers that are themselves vulnerable to infiltration by pests. These illegal aliens are tolerated better than human refugees seeking asylum.

Climate change is also impacting insects. It is ironic that dire warnings of an insect apocalypse have finally generated recognition that insects provide essential ecosystem services that we, and all other living organisms, cannot survive without.

On a positive note, never has there been greater potential to turn the tide. The internet has made public access to entomologists easier than ever, and it has afforded scientists and nonscientists alike opportunities to contribute to our collective understanding of insects. Digital cameras and mobile phones allow us to capture photos, videos, and audio recordings. We can upload our observations to social media for the public to marvel at, and for entomologists to use in their research. Participation in citizen science projects further benefits various species and their habitats. We can become Master Gardeners and Master Naturalists to help others restore native plant communities, or at least modify our own yards and gardens to be wildlife-friendly. National Moth Week, and Fourth of July butterfly counts have made bugwatching a social endeavor. Butterfly houses and insect zoos bring exotic tropical insects to cities and towns near you.

It is impossible to have even a passing interest in the insect world and ever be bored. Something new and fascinating is revealed daily, either to you, personally, to the global community, or to both. From A to Z, the words I associate with insects are amazing, marvelous, and zoophilia. Once you are finished with this book, dear reader, I hope you will be of a similar mind. If not, there are plenty of stories for which there was no room in this volume, and more discoveries await. Are you ready?

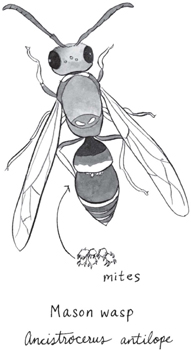

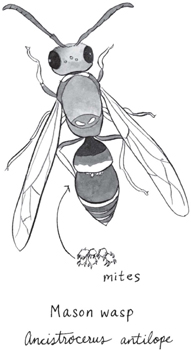

A carinaria

Some solitary bees, and mason wasps, have modifications to their anatomy designed exclusively for housing mites. An acarinarium is basically a carport where mites park themselves on the body of the insect. German entomologist Walter Karl Johann Roepke coined the term in 1920.

Many mites are parasitic, but the ones carried in acarinaria are mostly scavengers or fungivores. The wasps and bees are essentially transporting a cleaning crew to their nests, which are often located in linear tunnels divided into individual cells. Upon arrival at the nest, the mites disembark and commence feeding on materials that would pose a threat to the bee or wasps egg, larva, or pupa offspring, or the pollen or prey cached for it. In the case of the wasp Allodynerus delphinalis, the mite Ensliniella parasitica functions as a bodyguard of immature Allodynerus by chasing off or assassinating the tiny parasitoid wasps Melittobia acasta before they can kill the Allodynerus larvae or pupae.

Acarinaria take various forms. Some large carpenter bees (Xylocopa spp.) have a concave chamber on the anterior (front) face of the abdomen where mites gather in a communal group. Mites on some mason wasps have more deluxe accommodations, nearly every mite having its own garage located at the front of the second tergite (dorsal, or top, abdominal segment) and covered by the rear edge of the first tergite.

Aerial Plankton

The next time you look out the window of an aircraft, know that you are not alone. The air outside is full of an astonishing diversity and abundance of insects and other arthropods. Serious study of atmospheric insect life took flight in the late 1920s, but even with airplanes available, London entomologist John L. Freeman was attaching traps to kites and collecting specimens in England and the United States. P. A. Glick created a device to attach to planes and made systematic surveys in Louisiana, and also Mexico, from 1926 to 1931, mostly 2015,000 feet above the ground. Charles Lindbergh added a little data thanks to sticky glass slides affixed to the

Next page