I extend my heartfelt thanks to all who contributed to the completion of this work:

To my brothers of the Order of Friars Minor Conventual; to provincials past (Fr. Patrick Greenough) and present (Fr. Michael Zielke), who allowed me to pursue doctoral studies; to the friars of the Australian Delegation of Our Lady, Help of Christians, for their encouragement and sacrifice; and to my former guardian (Fr. Timothy Kulbicki) and friars of Convento SantAntonio alla Vigna, Rome, for their friendship and support during the writing of my thesis.

To the professors and staff of the Pontifical John Paul II Institute in Rome: to Dr. Stephan Kampowski for his careful supervision of my thesis; to Monsignor Livio Melina, whose writings first awakened me to a new way of looking at issues of morality and bioethics; and to Monsignor Pierangelo Sequeri and his council for awarding me the 2017 Sub Auspiciis prize.

To my former colleagues of the John Paul II Institute in Melbourne: to Professor Nicholas Tonti-Filippini ( 1956 2014 ), to whose memory this work is dedicated, for his wisdom and goodness; to the former dean, Professor Tracey Rowland, for her faith and encouragement of my academic pursuits; and to Associate Professor Adam Cooper, Liet. Col. Toby Hunter, Anna Krohn, Dr. Gerard OShea, Dr. Anna Silvas, Dr. Colin Patterson, Dr. Conor Sweeney, and Dr. Owen Vyner, for their professionalilsm, spirited conversation, and gentle introduction into the art of teaching.

And to Joseph Ratzinger / Pope Benedict XVI, whose love for truth and defence of human dignity is an enduring inspiration.

Introduction

Why Transhumanism?

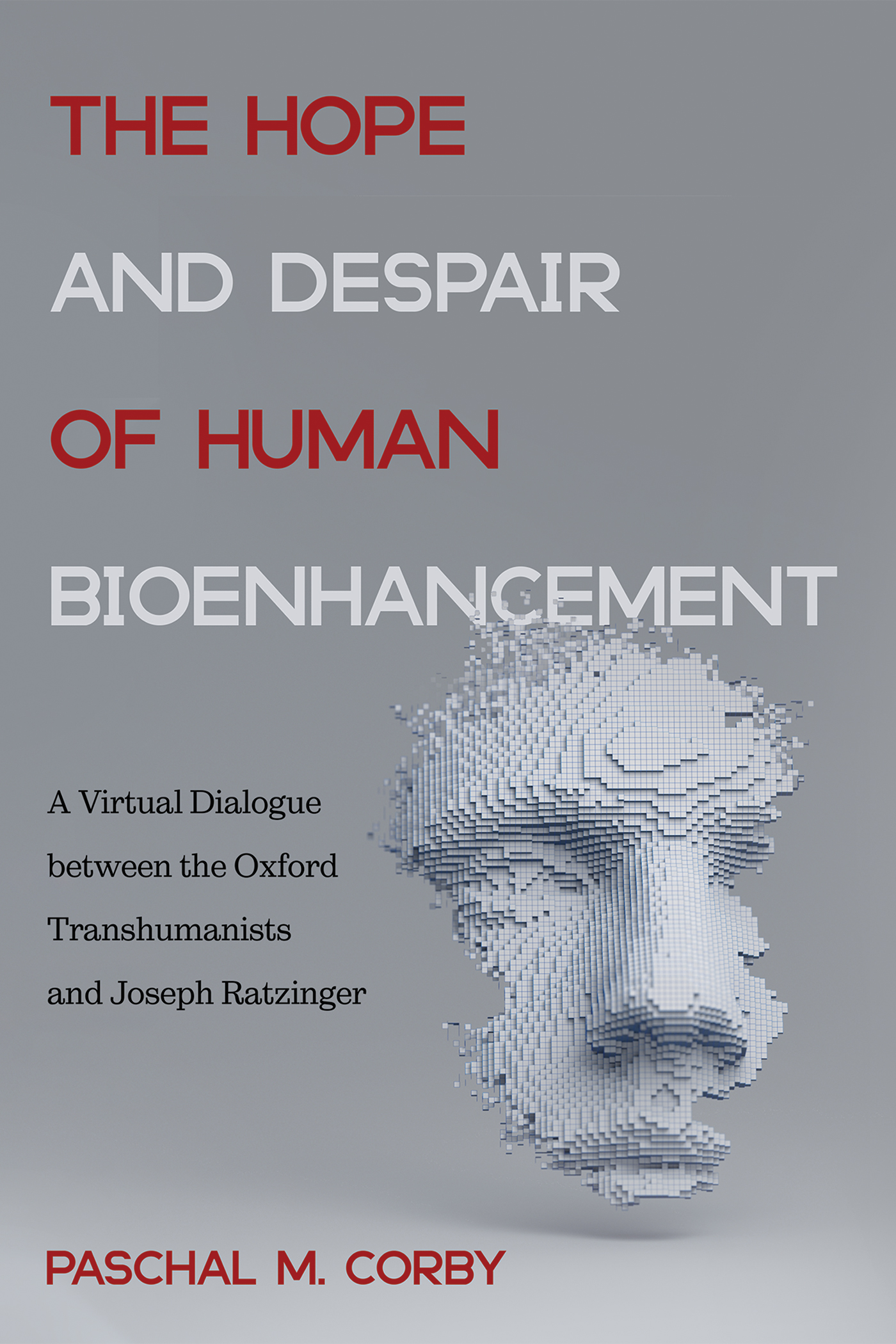

W hat I refer to throughout this work as the transhumanist project , cause , or movement encompasses a range of proposals, from simple measures to the improbable and bizarre, that aim at enhancing the human condition, using medical technology to move human beings beyond their natural limitations. Nick Bostrom is representative of the transhumanist cause in contending that current human nature is improvable through the use of applied science and other rational methods, which may make it possible to increase human health-span, extend our intellectual and physical capacities, and give us increased control over our own mental states and moods. Such enhancement is often termed transhuman or posthuman , implying not only an augmentation of human abilities, but also a qualitative change that takes one beyond the human species.

In light of its futuristic aspirations, with limited actual application, transhumanism might not seem to warrant serious reflection. Before the presence of real bioethical dilemmas such as new threats to life, the unjust distribution of healthcare resources, and the perennial issues surrounding life at its beginning and end, devoting time to an improbable possibility might appear to be a distraction or a luxury that we can ill afford. Yet the prospect of transhumanism has caught the imagination of not a few contemporary bioethicists and philosophers, inspiring centers of research, and sparking a lively debate between its supporters and critics.

While first impressions suggest something remote and abstract, it soon becomes clear that the transhumanist proposal treats of real concerns that touch on the very meaning of human life. In asking why one should take seriously the proposals of transhumanists, the prominent American bioethicist Leon Kass writes:

It raises the weightiest questions of bioethics, touching on the ends and goals of the biomedical enterprise, the nature and meaning of human flourishing, and the intrinsic threat of dehumanization (or the promise of superhumanization). It compels attention to what it means to be a human being and to be active as a human being.

In their pursuit to enhance and even transcend the current human condition, transhumanists caste shadows over the goodness of life and raise hopes for a bright and better future. Thus, even if many of its imaginative prospects do not eventuate, it demands a response here-and-now, for our hopes and aspirations define who we are. Accordingly, the primary concern of this work is not for the practicality of transhumanist claims, but a discernment of its worth as a proper object of human hope. In this context, hope becomes the leitmotif of this paper, in the context of a virtual dialogue between the Oxford Transhumanists and Joseph Ratzinger.

The Oxford Transhumanists

In presenting the transhumanist project, I will focus on what one might term the Oxford School of transhumanism, centered on the figures of Julian Savulescu and Nick Bostrom, and the Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics (Uehiro Centre) and the Future of Humanity Institute (FHI) respectively.

Julian Savulescu (b. 1963 ) is an Australian philosopher and bioethicist, currently based at Oxford University as professor of practical ethics and director of the Uehiro Centre. He is the current editor in chief of the Journal of Medical Ethics . He is a graduate of medicine (Monash University), and completed a PhD under the supervision of renowned bioethicist Peter Singer. To date, Savulescus main contribution to the field of human enhancement has been in the area of genetic selection of children, advocating selection of children with the best prospects of the best life, for which he coined the term Procreative Beneficence. He also advocates biotechnology to enhance cognitive, physical (including doping in sport), and moral capacities. In this latter regard, he has coauthored with Ingmar Persson Unfit for the Future: The Need for Moral Enhancement (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012 ). More generally, he has coedited works with Ruud ter Meulen and Guy Kahane ( Enhancing Human Capacities , Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011 ), and with Nick Bostrom ( Human Enhancement , Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009 ).