Routledge Revivals

The Development of the British West Indies 1700-1763

The Development of the British West Indies 1700-1763

Frank Wesley Pitman

First published in 1945 by Archon Books

This edition first published in 2018 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1917 by Yale University Press

1945 by Frank Wesley Pitman

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and welcomes correspondence from those they have been unable to contact.

A Library of Congress record exists under ISBN:

ISBN 13: 978-0-367-14254-4 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-0-429-03094-9 (ebk)

THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE BRITISH WEST INDIES 1700-1763

BY

FRANK WESLEY PITMAN

Copyright 1917, by Yale University Press

Copyright 1945, by Frank Wesley Pitman

Reprinted 1967 with permission

in an unaltered and unabridged edition

[Yale Historical Publications: Studies IV]

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 67-19509

Printed in the United States of America

TO

MY WIFE

PREFACE

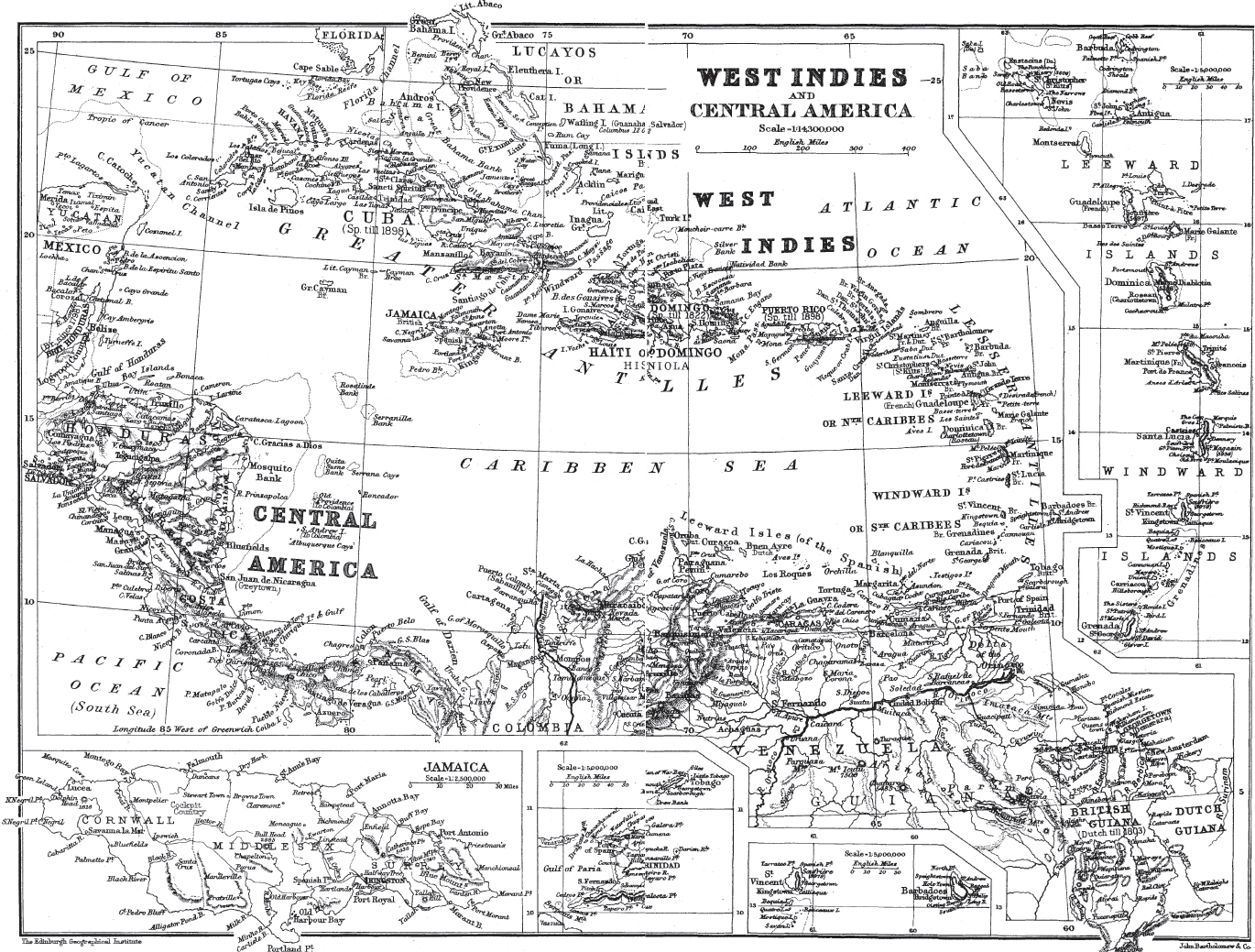

The West Indies have attracted, in recent years, an increasing interest from students of American colonial society. The more the history of that society is investigated the more do we realize the significance of the West Indies in the development and also in the disruption of the old British empire. For it was from the West Indies that England derived, perhaps, the greatest increment of wealth in modern times. The settlement of the West Indies seemed to the British and French in the eighteenth century the most vital of their outside interests. From the European point of view it is probably not too much to say that tropical colonies were then considered of far greater value than the temperate zone settlements in North America. To the British Northern Colonies, moreover, the West Indies were no less significant. For in the great slave communities to the southward Americans found the only great and permanent market for all their staples. It was the wealth accumulated from West India trade which more than anything else underlay the prosperity and civilization of New England and the Middle Colonies. The situation was analogous to that in the first half of the nineteenth century when the growth of our middle western states rested so largely upon the demand from the cotton planters of the lower south for foods and live stock, cheap access to whose market was made possible by the Mississippi River.

In this book, which in its original form was a doctoral dissertation, I have attempted an investigation of industrial and social conditions in the British West Indies in the effort to reach a better understanding of the part those islands played in the growth and dissolution of the empire. In the seventeenth century the British sugar islands served as an adequate market for northern produce and furnished tropical commodities in abundance for northern consumption and commerce. But the habit of free access to the foreign West Indies, especially in the first quarter of the eighteenth century, enormously stimulated the growth of North American industries and commerce. America was fast outgrowing, therefore, the empire to which mercantilists and West India planters desired to confine its trade. Americas progress and insistence upon free trade conflicted more and more with the interests and aims of British sugar planters. The latter, in an attempt to cheapen plantation supplies, monopolize the British and American sugar markets, and embarrass their rivals, secured the passage of the well-known Molasses and Sugar Acts discouraging all commerce with the foreign West Indies. It is conceivable that even this legislation might have been tolerable to North America if it had been accompanied with adequate territorial expansion in the tropics. But the peace of Paris revealed the governments intention of maintaining the boundaries of British dominion in the West Indies at substantially the old limits. Finally, the subsequent reforms in colonial administration made clear the determination to enforce all restrictions on colonial commerce. This course led straight to revolution. The interests and aims of American merchants and West India planters were clearly incompatible.

Thus the eighteenth was in general a century of restraint in politics and commerce for the British West Indies. Its history, despite a record of imposing wealth and growth in maritime strength, is wrapt in an atmosphere almost of pathos. For the settlement of the tropics was often a struggle with nature in her most violent moods. The jungle, earthquakes, hurricanes, disease, and an enervating climate seemed at times irresistible foes to the men who came to extract wealth from the soil. That end was achieved but seldom by small proprietors from the lower middle class of England. The production of sugar required above all an enormous outlay of capital, an abundant supply of the most expensive form of labor, slaves, and industrial organization on a large scale. When British capitalists with such equipment entered the field the small farmers could not hope to compete. The Anglo-Saxon society in the West Indies of the mid-seventeenth century gradually decayed. Great numbers died in the struggle with nature, many migrated, and others merged with the negroes and were lost to the white race.

It is impossible within the limits of this volume to describe adequately West India agriculture, slavery, and all the details of plantation economy. With a considerable amount of material already collected, I plan, however, to supplement the present work with a more intimate study of West India plantations and the society resting upon them. This work is based in the main upon the voluminous correspondence from colonial governors to the British Board of Trade. As the greater part of our sources for West India history is still in manuscript in the Public Record Office, the British Museum, and other archives, liberty has been taken to quote freely from contemporary writers. None of the older historians, such as Long, Edwards, or Schomburgk, had proper access to official papers. While many so-called histories are of little worth as records of the past, they remain, however, of permanent value as descriptions of the period in which they were written. This is preminently true of the works of Edward Long and Bryan Edwards. Since the material for this volume was gathered, admirable guides to the sources in England have been published by Professor Andrews and Miss Davenport. It is unnecessary, therefore, to enlarge here upon their nature. In the bibliographical note I have listed the principal sources which in the footnotes are indicated only by abbreviations.