The Hierarchies of Slavery in Santos, Brazil, 18221888

Ian Read

STANFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

STANFORD, CALIFORNIA

Stanford University Press

Stanford, California

2012 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University.

All rights reserved.

This book has been published with the assistance of Soka University of America.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press.

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Read, Ian (Ian William Olivo), 1976- author.

The hierarchies of slavery in Santos, Brazil, 1822-1888 / Ian Read.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8047-7414-7 (alk. paper)

1. Slaves--Brazil--Santos (So Paulo)--Social conditions--19th century.

2. Slaveholders--Brazil--Santos (So Paulo)--Social conditions--19th century.

3. Slavery--Social aspects--Brazil--Santos (So Paulo)--History--19th century.

4. Social status--Brazil--Santos (So Paulo)--History--19th century. 5. Santos

(So Paulo, Brazil)--Social conditions--19th century. I. Title.

HT1129.S265R43 2012

306.3'62098161--dc23

2011040195

Typeset by Bruce Lundquist in 10 /12 Sabon

E-book ISBN: 978-0-8047-7855-8

For Elysia & Luciana

(Per sentes ad astra)

List of Tables

List of Figures

Acknowledgments

Many people deserve my gratitude in helping me research and write this book. Margaret Chowning, Zephyr Frank, Mark Granovetter, John Padgett, William Taylor, and John Wirth were most influential at the earliest stages. To Zephyr, in particular, I owe much.

I worked in Brazil for more than two years on this book, but thankfully I rarely felt alone. Without the enormously helpful staff and amazingly well-organized archives in Santos and So Paulo, I would have found far less than I did. Special gratitude goes to Rita Cerqueira and Roberto Tavares at the Fundao Arquivo e Memria de Santos. I hope they remain victorious in their campaigns against the silverfish, firebrats, and all other formidable challenges of archival work in the tropics. Early drafts of Unequally Bound were scrutinized by Roderick and Jean Barman, Stanley Engerman, Herbert Klein, Linda Lewin, Aldo Musacchio, Richard Roberts, Lisa Sibley, and two helpful anonymous readers. This group gave me lengthy comments to ponder and act upon. Now that their suggestions are integrated into nearly every page and paragraph, there is additional evidence that books like this are never solitary projects. I alone, however, am responsible for any mistakes.

Historical research, especially of a country that was often more than six thousand miles away, is not cheap. I owe much to the financial support provided by the Division of Social Sciences at the University of Chicago, and from three programs at Stanford University: the Center for Latin American Studies, the Social Sciences History Institute, and, especially, the School of Humanities and Sciences. The Department of Education provided a Foreign Language Areas Studies grant and a much needed Fulbright grant. Finally, my final year of studies was supported by generous funding from the Mrs. Giles Whiting Foundation.

I continued to work on this project part-time as I began two years of adjunct teaching at the University of Puget Sound and the University of California, Berkeley. Many colleagues at these two institutions helped me survive the juggling act that rookie academics face in their first few years out of graduate school. Since then, I am happy to have found a new community of supportive colleagues at my position in Latin American Studies at the Soka University of America. It is heartening to work with Sarah England, Ted Lowe, Lisa MacLeod, James Spady, Michael Weiner, and the many others who make such a tiny university remarkably cosmopolitan.

At Stanford University Press, Norris Pope, Sarah Crane Newman, and Mariana Raykov were always kind, professional, and accommodating. Mary Barbosa ran the manuscript through a fine-tooth comb, correcting many of my mistakes.

I would be in no place such as this without the loving and encouraging community of family and friends. In what is becoming the typical American family, we are scattered to the four winds but use every excuse and technology to maintain our bonds. For my parents and old friends in Chicago, my aunts and grandmother in Wisconsin, my brother and cousins in Georgia, my brother in New Hampshire, and my large, extended Italian American family in Northern California, my love. When my two daughters are old enough to read this book, I hope they realize the significance of not turning a blind eye to all that degrades and dehumanizes. Finally, it is largely owing to the grace of my wife, Chanelle, that I find myself in a career that motivates and a family that sustains the most important kind of expression.

Abbreviations

AESP | Arquivo do Estado de So Paulo (State of So Paulo Archive) |

ANB | Arquivo Nacional do Brasil (National Archive of Brazil) |

ASCMS | Arquivo da Santa Casa de Misericrdia de Santos (Santos Santa Casa de Misericrdia Archive) |

BN | Fundao Biblioteca Nacional do Brasil (National Library of Brazil Foundation) |

CCS | Coleo Costa e Silva (Costa e Silva Collection) |

CDS | Curia Diocesana de Santos (Santos Diocese Curia) |

FAMS | Fundao Arquivo e Memria de Santos (Foundation of the Archive and Memory of Santos) |

FSS | Forum de So Sebastio (So Sebastio Forum) |

HS | Hemeroteca de Santos (Santos Newspaper Archive) |

MPCSP | Museu da Polcia Civil de So Paulo (So Paulo Civil Police Museum) |

PCNS | Primero Cartrio de Notas de Santos (First Notary Office of Santos) |

SCNS | Segundo Cartrio de Notas de Santos (Second Notary Office of Santos) |

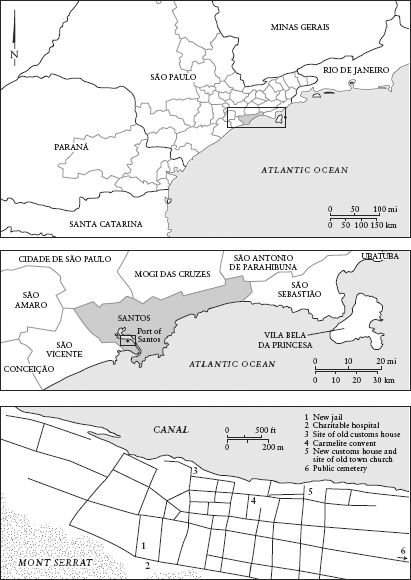

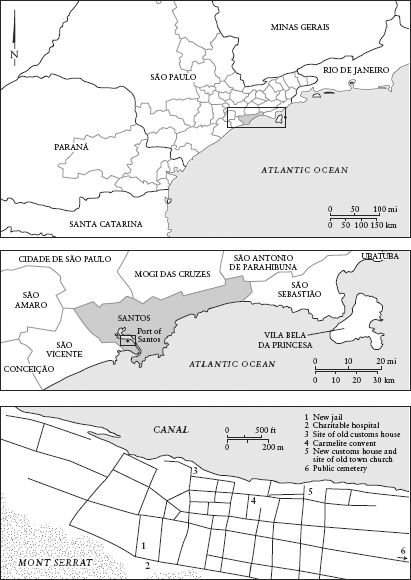

FIGURE 0.1

The Port of Santos Within Its Municipality and the Province of So Paulo

Introduction

This book looks at slaves and masters in Santos, So Paulo, a sliver-shaped coastal township in southeastern Brazil. The period of study begins with Brazils independence (1822), and ends when slavery was abolished (1888). I present evidence of differing slaves conditions of life and work, their treatment, and most important, the causes for this variation. Some slaves may have been privileged relative to other slaves (and even relative to some free poor), but slaves belonged to the most disadvantaged element in society because they lacked basic citizenry and property-holding rights and were socially degraded by their categorization as chattel. Slaves owned by masters with greater social and economic prestige stood a better chance of living healthier lives, working in relatively safer jobs, surrounding themselves with family and community, and even finding pathways out of slavery. For most other slaves, these paths remained unjustly blocked.