DISPOSABLE PEOPLE

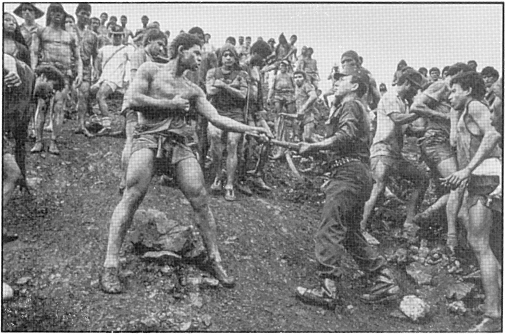

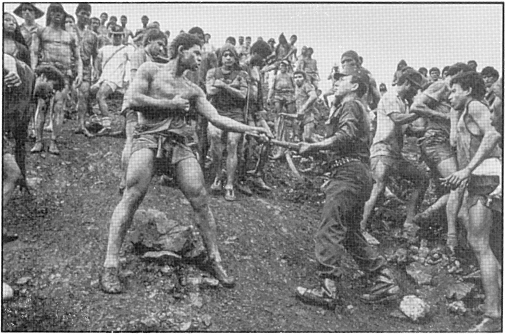

Gold diggers in Brazil. (Photograph 1998 Sebastio Salgado/Contact Press Images)

DISPOSABLE PEOPLE

New Slavery in the Global Economy

KEVIN BALES

REVISED EDITION UPDATED WITH A NEW PREFACE

University of California Press

Berkeley and Los Angeles, California

University of California Press, Ltd.

London, England

First Paperback Printing 2000

1999, 2000, 2004, 2012 by The Regents of the University of California

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bales, Kevin.

Disposable people : new slavery in the global economy /

Kevin Bales. Rev. ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-520-27291-0 (alk. paper)

1. Slavery. 2. Slaver labor. 3. PoorEmployment.

4. Prostitution. I. Title.

HT867.B35 2004

306.362dc22 2004008180

Manufactured in the United States of America

17 16 15 14 13 12

6 5 4 3 2 1

In keeping with a commitment to support environmentally responsible

and sustainable printing practices, UC Press has printed this book on

Rolland Enviroioo, a 100% post-consumer fiber paper that is FSC

certified, deinked, processed chlorine-free, and manufactured with

renewable biogas energy. It is acid-free and EcoLogo certified.

CONTENTS

photographs follow

PREFACE TO THE REVISED EDITION

I spoke of these people as captives. I talked about the harsh conditions they found in New York. They were malnourished, diseased. Infant mortality was high.

Dr. Michael Blakey heads up the African Burial Ground Project in New York City. More than four hundred slaves are buried in Lower Manhattan, and Blakey, a physical anthropologist, is drawing out the stories their bones tell. Blakey described how the remains of one young man show that he was probably trafficked from Africa to the United States:

He has evidence of treponemal disease, probably yaws. So bes been exposed to a tropical disease. He has evidence of hard work and some healed fractures in his spine. He also has the most subtle and elegantly filed teeth.

This mans bones bear witness to the destructive nature of slavery: he was no more than thirty-five when he died. There are also a very large number of small children buried in the cemetery. The impact of slavery on these families was enormous: When children die in large numbers, Blakey notes people feel a significant sense of loss.

Blakeys work ties us to slavery in the past. It shows us the reality of slaverys pernicious and ugly damage to human life. The slaves buried in Manhattan also help us to understand something very important: slavery has been, is, and will be part of our lives until we make it stop.

The slaves of Lower Manhattan and the slaves of today share many forms of suffering, among them the abuse and death of their children, the damage to their bodies through trauma and untreated disease, the theft of their lives and work, the destruction of their dignity, and the fat profits others make from their sweat. Slavery still exists in New York and around the world. Today it is often hard to see, but it is there. And like the slaves of the African Burial Ground in New York, the slaves all around us today have waited a long time for us and our governments to come awake to their existence.

When Disposable People was first published in 1999, many found its story shocking and unbelievable. Like the African Burial Ground Project, the research needed for the book was difficult to finance. But as the books message about slavery began to sink in, it opened up new areas of study and action. As the first work in decades to show the extent of slavery around the world, Disposable People became a lightning rod, drawing both the energy of activists and the anger of governments trying to conceal slavery within their borders. I was amazed and humbled by the hundreds of people who after reading the book declared themselves new abolitionists and dedicated themselves to work against modern slavery. As the book was translated into more and more languages (nine, so far, in addition to English), the expanding knowledge of new slavery triggered off more and more reactions in individuals, groups, churches, schools, and governments. When I was writing Disposable People I had dreams of how it might stir people to action, but my dreams were too small. The reality has been great and rapid change in the last five years, change that seems to be growing in its momentum and reach.

Underlying this momentous growth is the decision made in thousands of minds that slavery must end. The outcomes of this decision have been as various as imagination can make them. A film based in part on Disposable People opened up new areas of slavery to the public view and won two Emmys and a Peabody award. As awareness of modern slavery expanded, other films, books, scripts, poems, articles, law reviews, photo essays, theses and dissertations, songs, even a dance program, expressed peoples deeply felt desire to end slavery. For me, the growth in interest led to hundreds of interviews on television and radio, and in magazines and newspapers. The explosion of concern is being felt at the local, national, and international levels.

In the United States an important new law affecting slavery was passed at the end of 2000. Known as the Trafficking Victims Protection Act, it increased the penalties for human traffickers, brought new protections to victims, and ordered government departments to take action. This law has led to many initiatives and increased support for groups helping people who have been trafficked into the United States. Also in late 2000, the United Nations set out an agreement to fight trafficking in persons as part of a new Convention against Transnational Organized Crime. This protocol became international law on Christmas Day 2003, but has not yet been ratified by the United States. It will help bring national laws into agreement, which, since human trafficking is a crime that crosses borders, is crucial for successful prosecutions. Other countries too have written new laws. Now, as is the case for almost all laws against slavery around the world, the problem is getting those laws enforced.

One of the most exciting outcomes of this period followed the film that exposed slavery on cocoa farms in West Africa. The idea that the chocolate we feed our children, the chocolate we enjoy so much, could be tainted by slavery was disturbing. To their credit, chocolate companies in the United States and Europe moved quickly to address slavery in their product chain. Joining together, they made an agreement with antislavery groups, child labor organizations, and labor unions to take slavery and child labor out of cocoa for good. Now a well-funded new foundation has workers building programs in West Africa, and a system for inspecting and certifying cocoa is under construction. While some of the work has been held back by civil unrest in West Africa, the commitment and resources are there. For the first time since antislavery groups called for it 150 years ago, an industry is taking full responsibility for its product chain. It is a historic breakthrough, one that is serving as a model for other industries.