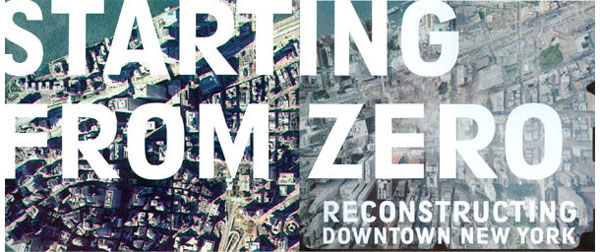

PUBLISHED IN 2003

BY ROUTLEDGE

711 Third Avenue,

New York, NY 10017

PUBLISHED IN GREAT BRITAIN

BY ROUTLEDGE

2 Park Square, Milton Park,

Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

COPYRIGHT 2003 BY MICHAEL SORKIN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. NO PART OF THIS BOOK MAY BE PRINTED OR UTILIZED IN ANY FORM OR BY ANY ELECTRONIC, MECHANICAL OR OTHER MEANS, NOW KNOWN OR HEREAFTER INVENTED, INCLUDING PHOTOCOPYING AND RECORDING, OR ANY OTHER INFORMATION STORAGE OR RETRIEVAL SYSTEM, WITHOUT PERMISSION IN WRITING FROM THE PU LISHER.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

SORKIN, MICHAEL, 1948

STARTING FROM ZERO : RECONSTRUCTING DOWNTOWN NEW YORK / MICHAEL SORKIN.

P. CM.

ISBN 0-415-94734-0 (HARDCOVER : ALK. PAPER) ISBN 0-415-94737-5

(PBK. : ALK. PAPER)

1. ARCHITECTURENEW YORK (STATE)NEW YORK21ST CENTURYDESIGNS AND PLANS. 2. NEW YORK (N.Y.)BUILDINGS, STRUCTURES, ETC. 3. MANHATTAN (NEW YORK, N.Y.)BUILDINGS, STRUCTURES, ETC. 4. CITY PLANNINGNEW YORK (STATE) NEW YORKHISTORY21ST CENTURY. 5. WORLD TRADE CENTER (NEW YORK, N.Y.) I. TITLE.

NA735.N5S67 2003

711.4097471DC21

2003008977

ON THE MORNING OF THE 11TH I SLEPT A LITTLE LATER THAN USUAL AND, FOR SOME REASON, DID NOT TURN ON THE TELEVISION WHEN I WOKE UP, LYING FOR A TIME IN A PRE-COFFEE HAZE . It was election day and I eventually pulled myself together to head downstairs to vote on the way to work. Leaving my building, I turned right towards Sixth Avenue and immediately noticed something was amiss: traffic did not seem to be flowing and the street was filled with people looking south. My immediate assumption was an accident, a police action. Getting to the corner, I turned my gaze downtown andthinking that what had happened was in the streetdid not immediately see the object of the crowds attention. And then I looked up.

The north tower of the World Trade Center was gashed and flames were licking at its faade well up. Next to itwhere the south tower should have stoodwas a shroud of gray smoke. People with radios gave me the news: planes had smashed into the tower, another had struck the Pentagon. What I saw from a mile uptown did not seem severe; fire, yes, but surely one that could be controlled. So improbable, so out of the range of my thinking, was the idea that the towers could actually fall, I dismissed what other onlookers were telling me, that the column of smoke I was staring at concealed a void, that one of the towers had already collapsed. Reassured from the depths of my architects expertise, I simply assumed that it was impossible. Within minutes the second tower was also gone.

Rushing back home, I tried frantically to contact people. My wife was stranded at LaGuardia. My parentswho live a few miles from the Pentagonwere safe. What next? The TV was on by now and the repeated reports became numbing. I decided to go vote, thinking this was democracys riposte to terror. On the way to the school that serves as our polling place, I met my friend George, hurrying to retrieve his daughter from a school further downtown. The street was filled with the rush of anxiety as people ran to find kids, friends, spouses. The polls were already closed, the election cancelled, and the sidewalk out front was filled with parents and kids. Heading down the block to St. Vincents hospital to donate blood, I found a queue snaking around the block, hundreds of people, a matter of hours to wait on line. And so I began walking down towards my studio, ten blocks north of the Trade Center.

Emergency vehicles screamed down streets now clear of traffic. From downtown, a numb crowd moved north in silent but measured flight. As I made my way south more and more people were covered in white ash. Below Canal Street, ash was falling and papers swirled and fell from the sky. The column of smoke rose and rose and everywhere was a horrific and unmistakable smell. Police barricades were appearing and I was just able to reach my building. The phones were out and I sat at the window staring at the maelstrom and listening to the radio. Eventually, the building was evacuated for fear of gas explosions and I trudged back north to reconsider everything.

This book is a record of a year and half of responses to the horrendous tragedy of September 11. It is, in many ways, very narrow in its focus, about the role of architecture and planning in an irrevocably altered New York. The discourse of reconstruction arose quickly and assumed a wide variety of guises and roles, eventually dominating all discussion of the event. Almost immediately there was a division between two reflexive responses: to rebuild intensively as both symbol and substance of regeneration and as rejoinder to the terror and, on the other hand, to leave the site free of commercial building, a permanent memorial. This work is both a reflection of the victory of the first approach and a record of alternative ideas.

The sites importance in the commemoration of the lives lost assumed peculiar character given the horror of the incineration and the resulting fragmentary remains of so many victims. As the task of recovery bore on, it became clear that this was a gravesite without graves, without bodies. The form of embodiment that symbols would thus be obliged to take was a terrible one, like a commemoration at Hiroshima or Auschwitz. This was not Gettysburg, not a place for serried tombstones; not a military site, however much the terror was described as an act of war. The massacre was of civilians, and they had been reduced to dust. We had all breathed their flesh.

My own feelings about the nature of commemoration began to take some shape after an early visit to the devastated site, seeing it up close for the first time in all its twisted enormity, still burning, still dangerous. It was clear that few intact bodies were going to be found, and the city had announced that it was obtaining a large number of DNA kits, in order to help identify the torn remains. I was disturbed at this precision in the face of such enormity and wondered why this scrupulosity was necessary, thinking it would simply cause further dismay and distraction for the bereaved, obliged to find a strand of hair on a comb or donate cells to help match a member of the family.

Not long afterwards, I expressed this to a friend who brought me up short. He lived with someone who had spent many years involved with the families of the disappeared in Argentina, and she had reported that what was of greatest comfort to those whose children had been murdered and erased by the junta was some shred of certainty about their fate. Closurethat overworked wordcame only with evidence that corroborated the finality known intuitively but unspeakable because the rituals of hope forbid it.

This insight suggested both the absolute importance of commemoration and the specificity with which it would invariably be understood. It also explained the infusion of the ground with the particulate of memory, some version of the sacred. Introduced at that moment was measurementthe process of recovery would involve repeated mapping of the meanings not just of the site but of the very idea of site. As the range of technical means were deployed to image and pin-point the fires still burning, the precise location of wreckage, the fallout of debris, the location of remains, a grim yet mesmerizing atlas was assembled that brought to public focus a way of seeing previously reserved for specialists and spies. Our gaze acquired a horrible but comforting objectivity.