Is there such a thing as an intergenerational community of justice? Do we owe solidarity to the dead? Are we morally obliged not to fall into a state of historical amnesia? These are philosophical questions of enormous scope and significance, and W. James Booth, with his formidable learning, intellectual clarity, and capacious insight, is uniquely well equipped to do them full justice. This task is even more urgent in a time when certain European governments (in Poland, for instance) have tried to legislate away their responsibility to the past.

Ronald Beiner, Professor of Political Science, University of Toronto

W. James Booth has given himself a very challenging task: to rationally justify the belief that we have obligations of justice owed to dead victims themselves, not merely to current and future persons who are linked in various ways to them. Drawing on classic Greek and contemporary literary works, he provides a powerful and deeply moving account that argues the dead are gone only in an embodied sense: they remain part of an enduring community all of whose memberspast, present, and futureare entitled to just treatment.

Jeffrey Blustein, Professor of Philosophy, City College

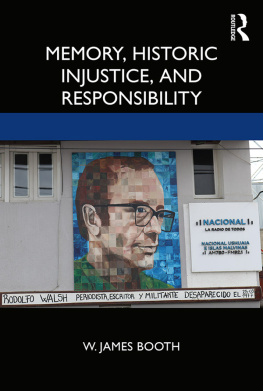

Memory, Historic Injustice, and Responsibility

What is it to do justice to the absent victims of past injustice, given the distance that separates us from them? Grounded in political theory and guided by the literature on historical justice, W. James Booth restores the dead to their central place at the heart of our understanding of why and how to deal with past injustice. Testimonies and accounts from the race war in the United States, the Holocaust, post-apartheid South Africa, Argentinas Dirty War, and the conflict in Northern Ireland help advance and defend Booths claim that caring for the dead is a central part of addressing past injustice.

Memory, Historic Injustice, and Responsibility is an insightful and original book on the relationship of past and present in thinking about what it means to do justice. A valuable addition to the currently available literature on historical justice, the volume will be of great interest to students and scholars of political science, philosophy, history, and law.

W. James Booth is Professor of Political Science and Professor of Philosophy at Vanderbilt University. His current research is focused on memory, identity, and justice. Before coming to Vanderbilt, Booth was on the faculties of McGill University and Duke University. At Vanderbilt, Booth teaches courses in the history of political thought, religion and politics, and graduate and undergraduate seminars on topics in contemporary theory.

First published 2020

by Routledge

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017

and by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2020 Taylor & Francis

The right of W. James Booth to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book has been requested

ISBN: 978-0-367-34221-0 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-0-367-34222-7 (pbk)

ISBN: 978-0-429-32454-3 (ebk)

Typeset in Bembo

by Apex CoVantage, LLC

Cover image: Wall mural of one of the disappeared of the Argentinian dirty war. Av. San Martin, Ushuaia, Tierra del Fuego, Argentina. Photographed by the author.

In loving and grateful memory of my parents, Bill and Madeleine Marie-Jeanne Booth

Earlier versions of parts of this study were presented at the: University of Virginia Political Theory Colloquium, American Philosophical Association (Eastern division) Annual Meeting The Ensuring Justice Across Generations Conference at Queens University, Belfast, Northern Ireland, the Historical Justice and Memory Conference, Melbourne, and in papers delivered at the University of Toronto, the UNC Institute for the Arts and Humanities, the Berry Lecture at Vanderbilt, and the University of Texas-Austin. I am grateful to the organizers and participants for their many critical questions and suggestions.

Warm thanks to my colleagues at Vanderbilt and elsewhere who commented on the arguments set out in the following pages: Lawrie Balfour, Ronnie Beiner, Jeffrey Blustein, Marilyn Friedman, Marc Heatherington, Nadim Khoury, Murad Idris, Emily Nacol, Mark Osiel, Lucius Outlaw, Jeff Spinner-Halev, Bob Talisse, and Janna Thompson.

I am grateful to the late Edward Daly, formerly Bishop of Derry, and to the late Leo Wilson of Belfast, both of whom helped me understand the Northern Irish Troubles.

I owe a special debt to my Routledge editor, Natalja Mortensen, the Presss referees, and to Charlie Baker for their tremendously helpful advice and assistance.

My wife, Jane, and daughter Maddy have generously put up with years of conversation about the topics of this book. Many thanks!

Revised material from two articles of mine appears in this study with permission. They are From This Far Place: On Justice and Absence. American Political Science Review , 105 (2011): 750764 and The Color of Memory: Reading Race with Ralph Ellison. Political Theory 36 (October 2008): 683707.

In the Land of the Unseen

In Sophocless Electra , Electra asks How when the dead are in question can it be honorable not to care? Caring for the dead is one of the most basic of human practices: for their bodies, their last wishes, and for remembrance of them. This is a book about one of the ways in which we care for the dead: by doing them justice. Haunting all these practices, including bringing justice to the dead, and making them perplexing, is what we might term a vernacular form of naturalism: that what can be seen with our eyes, the world as an object of possible experience, tells us that the dead are radically absent, indeed nonexistent as persons, a mere handful of dust. They are, as Aeschylus writes, in the land of the unseen [ amauron ], in relation to which we, the living, occupy a very far place.

Yet we do nevertheless care about the dead, including addressing previously unanswered historical injustices that marred and, in some cases, ended their lives. In that way, we allow (as Axel Honneth argues) for a certain disempowerment of our everyday naturalism about the dead. In practice, it is reflected in the drive to give a response to the wronged, even (or so I shall argue) the wronged who are dead, if only that of discovering and proclaiming the truth about past crimes and their victims.

In the Phaedo , Plato maps some of this archipelago, bringing together the living, the dead, justice, and philosophy. His interest in this is certainly not one with Electras. For her, the challenge emerges from a concern for the wronged dead understood as giving them justice. For Plato, on the other hand, it is the status of the world as it is given to us through the senses and of those things which are not present to the senses: justice itself, the dead and so on. So in its central focus, doing justice to the dead, the present study does not intersect with the Platonic corpus. Nevertheless, as a guide to the land of the unseen, Plato is extraordinarily helpful in his observations on the place of absence in our world. In the beginning pages of this section, then, I follow him briefly as he guides us through some of this archipelago.