If Israel should ever fail to protect her own, she would cease to have meaning. We have been forced into aggressive defense and the stakes keep getting higher.

In the end, we may have to choose between action that might pull down the Temple of Humanity itself rather than surrender even a single member of the family to the executioners.

Survival in other circumstances is not survival at all. And all of us, whatever our race, wont be worth a damn if we buy our lives at the cost of our conscience.

Yerucham Amitai, Former Deputy Chief, Israeli Air Force.

From a conversation with William Stevenson while flying over the Temple of Solomon, March 1970

Copyright 1976 by William Stevenson

First Skyhorse Publishing edition 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

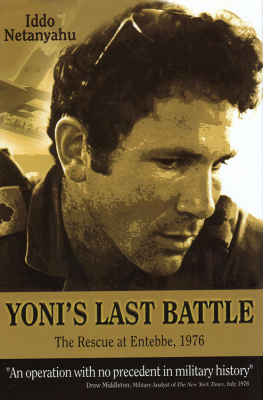

Cover design by Rain Saukas

Print ISBN: 978-1-62914-442-9

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-62914-849-6

Printed in the United States of America

INTRODUCTION

During the first hour of Sunday, July 4, 1976, a raiding party escaped from the heart of Africa with more than a hundred hostages held by a black dictator. Operation Thunderbolt struck across 2500 miles with airborne commandos in a spectacular 90-minute battle against international terrorism.

In Washington, while Americans began to celebrate the 200th anniversary of declaring independence from British rule, the news came first through the powerful electronic ears of the National Security Agency, which picked up terse radiophone conversations between Israeli troops fighting in Uganda, one of Britains last colonies to gain independence.

The messages in Hebrew passed between armed jeeps, infantry carriers, four giant Hercules transport planes, two Boeing 707s, and a black Mercedes that appeared to, but did not, belong to President Idi Amin Dada, sometimes known with graveyard humor as Big Daddy. One of the 707s contained the chief of the Israeli air force and an entire battlefield command center, circling five miles high.

Not all of this was immediately evident in Washington. Uganda must have seemed as remote as the moon to the NSA translators; and indeed the African state is better known for its famous Mountains of the Moon than it is for having any significance in world politics. But the reports reaching Secretary of State Henry Kissinger made sense. He had been warned just minutes earlier that an Israeli long-range penetration group of some five hundred soldiers and airmen had made its way down the Red Sea, around Russian-built radar watchdogs, between hostile Arab states, and across part of Africa to swoop along the Rift Valley and into Entebbe.

Israel waited until the last minute to tell the United States about this unprecedented military operation. A small group of men in Jerusalem shouldered the full burden of responsibility. For a whole week they had wrestled with a crisis that should have drawn the support of other governments but did nota crisis for which there were no ready-made answers, no previous experiences on which to draw, and no perfect solutions.

Israels ambassadors informed Henry Kissinger and other foreign ministers in order to prevent an alarmed military reaction. They made their disclosures in response to a single coded message transmitted from Jerusalem to the capitals of the world, and delayed so that no foreign government would have time to protest or interfere.

The crisis that Israel faced alone was one that revived bitter memories of other tragedies when Jews had been abandoned to their fate. In reconstructing events leading to those 90 minutes at Entebbe, I was not told by the Israelis that they were haunted by memories of the Holocaust, pogroms, and inquisitions. Not one of the soldiers, airmen, politicians, and statesmen drew an analogy. The facts spoke for themselves. When I sat with Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin in his Jerusalem office, for example, there was no trace of self-pity in his account of the preceding days of agonizing soul-searching. There was no reproach. When Defense Minister Shimon Peres recalled the desperate moves to win international help, he made no judgments. When the chief of staff, General Mordechai Gur, suddenly buried his head in his arms in a brief betrayal of fatigue, it was merely the gesture of a man expressing relief that Jews can still count on one unfailing protectorthe state of Israel.

And this was what Thunderbolt was all about. That Israel does have the most powerful of reasons for its existence. Without Israel the hostages at Entebbe would have died or become pawns in a new kind of guerrilla warfare aimed at destroying the decencies. And the hostages were Jews. And officially, no other government wished to save them by military action.

Thunderbolt marks a turn of the tide, however, in the free worlds response to the new techniques of terror. For years we have become conditioned to blackmail and anarchy, so that the hijacking of an Air France airliner on its way from Athens to Paris seemed almost routine. Flight 139 originated in Tel Aviv on the morning of Sunday, June 27. At the time, the men who would spend the rest of the following week in a sleepless battle of wits were going about their business in the most undistinguished way. Some were soldiers with civilian jobs; pilots who were also university students; politicians with a taste for philosophy or archaeology. I know that one man who shot dead an archterrorist at Entebbe was on this Sunday discussing sculpture with an old schoolmate in the artists colony of Safed.

Flight 139 disappeared for a while from the map and from the minds of most newspaper readers except those with relatives aboardand except for Israelis, who sensed yet another challenge to their right to exist. Yet Flight 139 was important to those of us who are not Jews but share the same values.

There were a lot of strange aspects to the saga of Flight 139. The terrorists who hijacked it were executing a carefully conceived plan. They were endorsed by the president of the Republic of Ugandathe first time a modern nation and its leader became the protector and spokesman for pirates and political blackmailers. They were nourished by an international terrorist organization whose headquarters were in the neighboring territory of the Soviet Unions strategic ally in Africa, Somalia. They declared war, for all intents and purposes, on Kenya, which has resolutely resisted the influence peddlers from the Soviet bloc and China.

The terrorists were led by a German man and woman whose behavior reminded at least one hostage, himself bearing tattooed numbers from a concentration camp, of Nazis. The name of The Jackal, an assassin with worldwide connections, arose time and again. The Jackal is not a fictional villain: he is a technician of death employed by revolutionaries of sophisticated backgrounds. Their negotiations with the state of Israel, for example, were conducted with the arrogance of men and women sure of powerful backers. One of their sponsors was Libya, where Flight 139 first landed to refuel: Libya, which has spent part of its enormous oil revenues on guerrilla groups$50 million to revolutionaries in Lebanon; $100 million to Black September, the terrorist wing of Al Fatah; and millions more to such agents of arson and assassination as the Angels of Death in Eritrea. The names mean nothing to most of us until too late. The names meant little or nothing to the passengers on Flight 139 whose lives were to be bartered for jailed terrorists, an exchange so common now that we have come to accept it as normal.