First published 1926 by

FRANK CASS AND COMPANY LIMITED

Published 2014 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxfordshire OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

First issued in paperback 2014

First edition 1926

New impression 1967

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in anyinformation storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

ISBN 978-0-7146-1091-7 (hbk)

ISBN 978-0-4157-6031-7 (pbk)

Preface

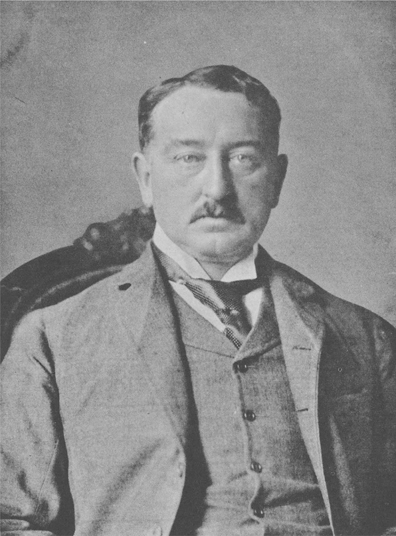

T HE evolution of the British colonies which bear the name of Rhodes, their founder, has never, so far as I am aware, been described as a consecutive whole. Disconnected episodes have at different times excited attention and provoked controversy, but their correlation has not yet been presented to English readers and many of their details have been published in a garbled shape. My justification for attempting to piece the story together and to clear away some misconceptions lies in the fact that I lived in various parts of Southern and Northern Rhodesia for twenty-three years, and was in close personal contact throughout with the men who participated in the events of their stirring history. Many of these men have passed into the realms of silence, and before long no eye-witness will be left.

I desire gratefully to acknowledge the assistance which the Board of the British South Africa Company has rendered by allowing me to refer to early records and original reports. I wish also to record my indebtedness and thanks to Mr. E. A. Maund and Mr. Leo Weinthal, C.B.E., for some of the photographs, to Mr. H. H. Kitchen of the British South Africa Company for drawing the maps, and to Mr. J. G. MacDonald, O.B.E., and other Rhodesian friends for supplying deficiencies in my narrative. In preparing the early was greatly helped by the late Mr. Rochfort Maguire, President of the Chartered Company, who was intimately connected with many of the events recorded in them.

It is perhaps impossible for one who has served the Company from its inception to escape altogether the imputation of partiality, but I have honestly endeavoured to present the simple truth and to gloze over no shortcomings.

H. M. H.

London ,

February , 1926.

Chapter I

The Genesis of the Movement

T HE project upon which Cecil Rhodes embarked thirty-six years ago, of creating a British Colony in the heart of Africa, has long since passed beyond the experimental stage. Its justification is now in the hands of the small but enterprising body of settlers in Southern Rhodesia who have lately, on their own initiative, shouldered the management of the great estate provided for them by the genius of its founder and by the patient and only partially requited labours of that remarkable corporation the British South Africa Company, whose history is, in fact, the history of the country itself.

The genesis of the movement which ultimately received the sanction of a Royal Charter may be traced to two principal influences.

The first of these was the persistent tradition, handed down from remote antiquity, that vast deposits of gold lay ready for the miner in Central South Africa, and the second was the impulse which came upon Englishmen, almost suddenly, in the latter part of the nineteenth century, to acquire fresh tracts of Africa for future development, to link South with North, and to create a Tom Tiddlers ground from which other European Powers should be excluded.

In the beginning these two influences operated independently and either of them might in time have become strong enough, unaided by the other, to have inspired a British enterprise. When they were ultimately merged they advanced with a rush which swept aside all opposition, and what had at first been the dream of a few adventurers rapidly assumed the form of a solid commercial movement.

It is proposed at the outset to trace briefly the history of each of these two ideas up to the point where they became united in the mind of one man, and as the gold was the earlier attraction in point of time, so it will be dealt with first in this narrative.

It is unnecessary to do more than recall the legend of wealth which, through ancient and mediaeval history, has clung about Mashonaland, long thought to be the Ophir of Biblical lore. It was this that prompted the Portuguese expeditions of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries: it was for gold that the miners of Zimbabwe, unidentified to this day, built the walls and towns, and sunk the shafts, which remain as enduring monuments to their industry, and it was the gold-glamour which made the mysterious Empire of Monomotapa a household word in Europe up to comparatively recent days. The builders of Zimbabwe played their part and passed from the stage; the coast lands were occupied in turn by Arab traders and Portuguese adventurers. None of these were destined to establish themselves in the interior as a nation; the barbarous Kaffir tribes survived them all, and one is sometimes driven to speculate as to whether this virile race may not be destined to outlast even the present colonists of South Central Africa.

The history, mythical or actual, of these successive occupations belongs to another period, and has been well told by other pens. The following pages will deal with the latest phase only of Rhodesias long history, during which the vague and doubtful rumours of hidden riches have gradually taken concrete shape in blocks of veritable gold.

The story dates back fifty or sixty years, and begins at a time when Mashonaland and Matabeleland were unknown, save to a few intrepid hunters who toiled painfully into the interior from Durban or Capetown, and risked health and life in the pursuit of ivory. One of these, Henry Hartley, a well-known elephant hunter, whose wanderings led him more than once into the remote regions of Mashonaland, was struck by the shallow excavations and heaps of quartz which he saw in many parts of the country, and which were obviously the work of human hands. Hartley was one of the British settlers of 1820, and had his home at Bathurst in the Cape Colony, whence for many years he made expeditions into the interior for trade and hunting, but it was not until 1866 that he was able to put into practice the idea of obtaining scientific investigation of the mineral potentialities of the quartz reefs, which he knew to be so widely distributed in this part of Africa. In that year he fell in with a young German scientist named Carl Mauch, and engaged or invited him to accompany his next expedition.

![Robert Hugh Benson [Benson - Robert Hugh Benson Collection [11 Books]](/uploads/posts/book/139831/thumbs/robert-hugh-benson-benson-robert-hugh-benson.jpg)