Copyright 2006 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4122

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Parkin, Katherine J.

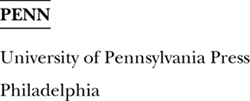

Food is love : food advertising and gender roles in modern America / Katherine J. Parkin.

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8122-3929-4 (alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-8122-3929-6

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Sex role in advertisingUnited StatesHistory. 2. AdvertisingFoodUnited StatesHistory. 3. Women consumersUnited StatesHistory. 4. Women in advertisingUnited StatesHistory. 5. Men in advertisingUnited StatesHistory.

I. Title.

HF5827.85.P37 2006

659.19'66400973dc22 | 2006042227 |

For ChrisIntroduction

My great-grandmother, Mary Morris, was born in 1906 and stopped school in the third grade, working first in domestic service, then at Jenkinss glass factory, and finally retiring as head of Krogers dairy department. Living until 1997, she witnessed many remarkable changes in American society. Certainly one of the most notable transformations took place in her kitchen and in kitchens across the country. Convenience foods sped up the cooking that had previously taken long, labor-intensive hours. Yet even as the cooking got easier, she, and not her husband, was responsible for it. This was true even though all of the other housework responsibilities fell to her and she worked outside the home for wages. However, she did not always make the food and often used the supermarket and the bakery to supply her feasts. Mary wanted to show her love with food, but she demonstrated her love by procuring and preparing food, not necessarily making it at home from scratch. Indeed, as she was able, Mary Morris bought more and made less, reflecting a growing trend, as more Americans bought prepared foods for their convenience.

Still, throughout the twentieth century, the ideology that identified women as homemakers and men as breadwinners held strong, even as a different reality strained the ideal. Mary Morriss role was not unique; cultures around the world and across time have bound women, food, and love together. American society and advertising in particular have envisioned the preparation and consumption of food in distinctly gendered terms. While everyone eats food, women have had sole responsibility for its purchase and preparation. By commodifying these attitudes and beliefs, womens magazines and food advertisers have promoted the belief that food preparation is a gender-specific activity and that women should shop and cook for others in order to express their love.

Many scholars have considered the role of advertising in American society, but few have considered the centrality of food advertising in shaping twentieth-century gender roles. Big-ticket items like automobiles and appliances have attracted many analysts of advertising, while others have examined what seemed to be more explicitly gendered ads for Food ads offer a unique opportunity to explore the cultural discourse about American gender roles because of the centrality of food to the human experience. Unlike most other advertised products, food at its core is not a luxury. While advertisers peddled items that some might have wanted, food was something that people needed. This study focuses on the broad category of food, generally ignoring non-essential items like beverages (coffee, liquor) and candy (gum, chocolate). People of all classes have always had to buy food, as opposed to items more easily borrowed, put off, or done without. Moreover, people consumed food on a daily basis, usually several times a day.

When national advertising began in earnest at the turn of the century, food manufacturers quickly dominated in spending. What food lacked in ticket price, it compensated for in tremendous sales volume. While food advertising accounted for only one percent of the fledgling advertising agency N. W. Ayers revenues in 1877, 24 years later the nations largest advertising firm took in 15 percent of the revenues from food advertising, the largest of any category. In 1920, the food industrys outlay of well over $14 million for advertising far outstripped its closest rival, toilet goods, which spent just over nine million dollars. In the Ladies Home Journal, food ads in the early 1920s comprised about 20 percent of total ad revenues. While spending in other categories grew over the century, particularly health and beauty products; cigarettes; liquor; and automobiles, food companies remained into the next century one of the preeminent advertising categories in the country. Indeed, many early food-advertising leaders, such as Campbells soup, Kelloggs, Aunt Jemima, and Quaker Oats, continued to retain a strong presence. A 1993 assessment of the industry found that food advertisers spent about $7.6 billion in the mass media in 1990, with spending rising 13 percent between 1980 and 1990 and 4.5 cents of every food dollar poured back into advertising.

Food advertisers had reason to believe that their investment might pay off. Historian Stanley Lebergott found that at the outset of the century, Americans typically spent more on food than citizens of almost any other nation. While some thought that it would be impossible to maintain such consumption patterns, American spending on food continued to grow. As one advertising firm proclaimed in 1958, millions of families now can afford to place quality, style and convenience ahead of price. The increase appears to have stemmed primarily from changes in foods purchased, including more food bought and eaten away from home, and greater reliance on more expensive items, such as meat and bakery products.

During the second half of the century, consumers increasingly spent food dollars on meals outside the home. Periodic studies and articles

The development of new machinery in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries changed the food preparation process. With the subsequent introduction and increased availability of new foods and products, conceptions of cooking changed. The most significant change in American eating habits was the widespread adoption of canned goods. Between 1909 and 1929, spending on canned goods consumption rose nearly six times, from $162 million to $930 million. While cooking used to involve multiple procedures and a variety of utensils and ingredients, according to Greenwald, the definition of cooking expanded to include the assembly of prepared elements.

Some observers resisted this new conceptualization of cooking and used terminology like traditionalist or contemporary as they assessed the trends. For example, in a 1998 study, the Canned Food Alliance asked female respondents to characterize themselves as Suzy Homemakers or Prepared Food Paulas. A slight majority of respondents between ages 25 and 39 claimed they still make almost every evening meal at home, from scratch, although forcing women to consider and verbalize whether or not they were homemakers undoubtedly skewed the results. When asked to define homemade, consumer opinions varied, but the majority (68 percent) believed that homemade still means made at home from scratch. About a quarter defined homemade as anything made at home, including prepared, frozen or microwavable foods.