Women at the Wheel

WOMEN

AT THE

WHEEL

A Century of Buying,

Driving, and Fixing Cars

KATHERINE J. PARKIN

Copyright 2017 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used

for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this

book may be reproduced in any form by any means

without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Parkin, Katherine J., author.

Title: Women at the wheel : a century of buying, driving, and fixing cars / Katherine J. Parkin.

Description: 1st ed. | Philadelphia : University of Pennsylvania Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017009400 | ISBN 978-0-8122-4953-8 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Women automobile driversUnited StatesHistory. | Sex roleUnited StatesHistory20th century. | AutomobilesUnited StatesHistory. | Automobile drivingUnited StatesHistory. | AutomobilesUnited StatesHistory.

Classification: LCC HE5620.W54 P37 2017 | DDC 629.28/3082dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017009400

To Quinn and Vivian,

my daughters, my loves

CONTENTS

LIVING IN THE SUBURBS in the late 1950s, author Betty Friedan preserved her writing time by having a taxi transport her children to school. Friedan realized that driving did not free her from the yoke of domesticity she so famously exposed in her classic, The Feminine Mystique. Instead, she recognized that for most women the car was principally a tool in service of the type of never-ending domestic work expected of them. Not only did women not find liberation on the road, but they also found themselves targeted by spurious stereotypes of women drivers. These myths, including a belief that women were excessively cautious, spatially inept, and fundamentally incompetent drivers, persisted with little change over the course of automobile history.

Yet at the same time, in spite of these negative associations, women needed cars. The countrys shift to the suburbs, facilitated by the emergence and eventual dominance of the automobile, meant that women had to go out and get products and services once delivered to the home. While one historian contended that driving represented liberation from the household, home economist Christine Frederick noted that moving to the countryside meant that in addition to all of the farm production she was responsible for, she also had to serve as a chauffeuse. Most women discovered that to facilitate everything from daily milk delivery to doctors care, they needed to drive. Their work also included taking their husbands to the train or their jobs and their children to school and activities. Across the century, even those women with the

Most twentieth-century white, middle-class, American women found their lives defined by domesticity, and the use of their car principally affirmed their gender identity. Friedans decision to pay someone to drive her children to school reflects the insights she brought to bear on a nascent feminist movement. Few have questioned, as Friedan did, the value of having women spending hours behind the wheel chauffeuring their husbands to work and their children to school, practices, and lessons. Yet women discovered that driving mirrored their other domestic responsibilities, as it was structured around others needs, it was rote, and it was never-ending. For millions of women, their experience with the car fundamentally differed from that of men. The car was for most men an assertion of masculine identity, predicated on power, control, and freedom. Even when men drove in more mundane circumstances, ferrying their families or driving to work, their ownership and default position behind the wheel of the car left them with more authority than women could generally assert.

Most women found their legitimacy as drivers compromised by a cultural expectation that placed men in the drivers seat and relegated women to the passenger side of the car whenever both were present. The cultural representations of mens control of cars served to dissuade women from assuming an identity as a driver. Womens historical association with the car, therefore, was primarily as a passenger or as a driver in service of their work as wives and mothers. The number of women who found independence when they slid behind the wheel was relatively small.

In part because of their customary role as passenger, some women also found themselves vulnerable to men who had control of an automobile and whisked them away from the watchful eyes of their families and communities. Moving beyond the front porch or the neighborhood created both opportunity and vulnerability for women. From their earliest experiences with cars, young women were taught to be wary of men, especially those offering rides or assistance. Cautioned about the risks of predators and the devil wagon, most women, into the twenty-first century, had a much more circumscribed automotive experience than men.

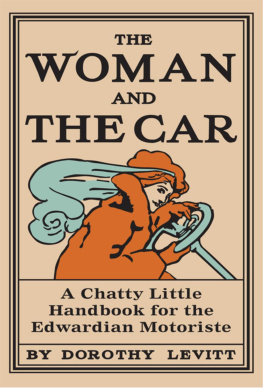

Contemporaries of the first women to drive cars generally did not consider their actions significant, or even positive. More than a dozen men laid claim to being the inventor of the American automobile, dating to 1893, and countless more sought acknowledgment as the first to break driving records for speed and distance. Before the emergence of the womens movement in the 1960s and 1970s, however, few women celebrated their vehicular accomplishments as the first American woman to drive a car, be licensed, or drive long distances. While some have imagined the role of cars as transformative, in truth cars only offered women a wider range of possibility in their everyday lives.

Indeed, it was a man who made one of the earliest claims of a woman behind the wheel. Automobile inventor and manufacturer Elwood Haynes proclaimed that his secretary, Mary Landon, had been the first woman ever to drive, in 1899. Businessmen like Haynes needed to grow the number of drivers nationally; into the 1920s, only a small percentage of women drove. His story line was clear: Driving is so easy and safe that even women have historically done it, and he either resurrected or created a story about Landons adventure. Highlighting Landon in 1928, though, also revealed how short-lived her automotive independence was, as she no longer drove and had not even owned a car for twenty years.

FIGURE 1. Manufacturers sought out women drivers in the early twentieth century by assuring them that their cars were easy to drive and reliable. This 1904 Haynes ad drew on the popularity of a vaudeville performer to explain why a woman would need a vehicle to take her far from home and count on getting back without trouble.

This type of backhanded acclaim pervaded the attention accorded to early women drivers. As Kokomo, Indiana, residents celebrated their centennial in 1965, they revived the claim that Mary Landon was the first woman driver. A newspaper article celebrating her history and participation in the festivities, however, still concluded that the explanation for her revolutionary turn behind the wheel stemmed from the fact that she was tricked into it by Haynes. Even as the local media granted Landon recognition and thought her story newsworthy, they simultaneously characterized her as duped into driving.

Next page