I TATTI STUDIES IN ITALIAN RENAISSANCE HISTORY

Published in collaboration with I Tatti

The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies

Florence, Italy

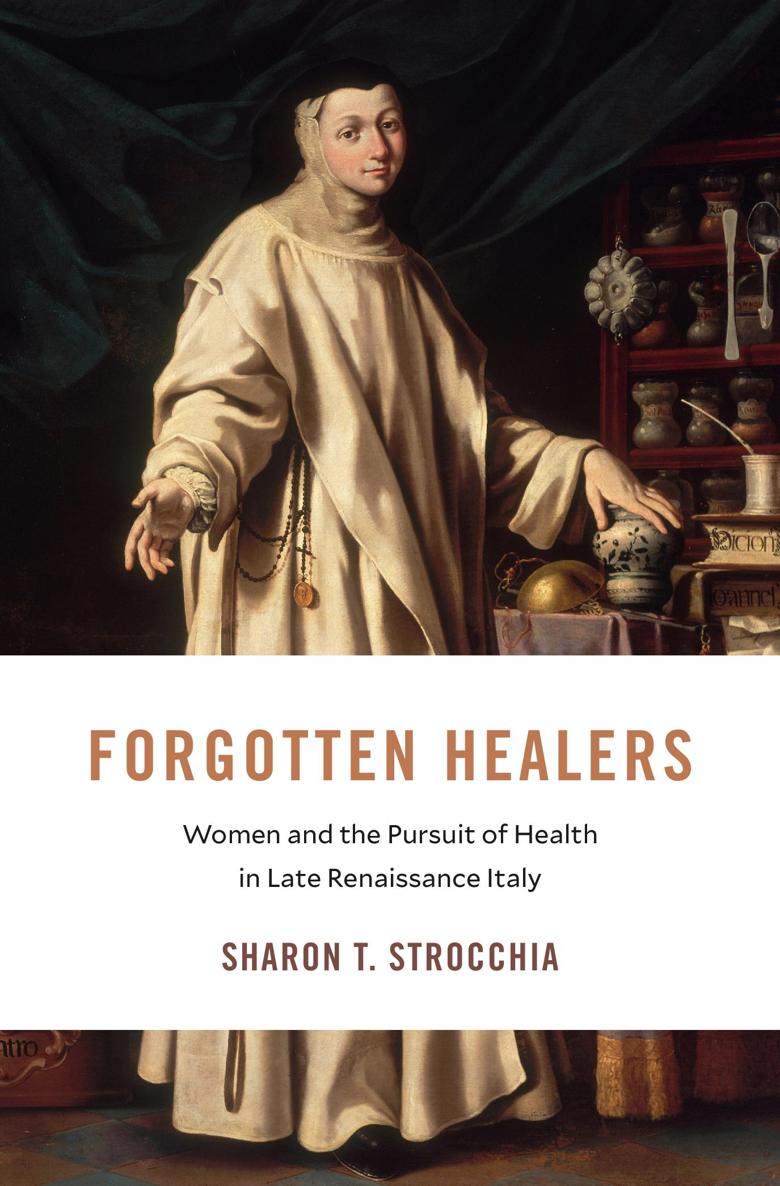

FORGOTTEN

HEALERS

Women and the Pursuit of Health in Late Renaissance Italy

SHARON T. STROCCHIA

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2019

Copyright 2019 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Jacket design: Tim Jones

Jacket artwork: Portrait of an unknown Florentine nun pharmacist by Alessandro Gherardini, 1723, courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest.

978-0-674-24174-9

978-0-674-24345-3 (EPUB)

978-0-674-24346-0 (MOBI)

978-0-674-24344-6 (PDF)

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Strocchia, Sharon T., 1951 author.

Title: Forgotten healers : women and the pursuit of health in Late Renaissance Italy / Sharon T. Strocchia.

Other titles: I Tatti studies in Italian Renaissance history.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : Harvard University Press, 2019. | Series: I Tatti studies in Italian Renaissance history | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019012378

Subjects: LCSH: Women healersItalyHistory16th century. | Women healersItalyHistory17th century. | Women in medicineItalyHistory16th century. | Women in medicineItalyHistory17th century. | Medical careItalyHistory16th century. | Medical careItalyHistory17th century. | MedicineItalyHistory16th century. | MedicineItalyHistory17th century.

Classification: LCC R517 .S77 2019 | DDC 610.94509/031dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019012378

In memory of

STELLA STROCCHIA

Mother, teacher, caregiver

CONTENTS

- The Politics of Health at the Early Medici Court

- Gifts of Health

- Medical Exchanges between Court and Convent

- The Business of Health

- Convent Pharmacies in Renaissance Italy

- Agents of Health

- Nun Apothecaries and Ways of Knowing

- Restoring Health

- Care and Cure in Renaissance Pox Hospitals

Fig. 1.1Jacopo Pontormo, Portrait of Maria Salviati de Medici with Giulia de Medici, circa 1539

Fig. 2.1Letter from Queen Leonor of Portugal to the Abbess of Le Murate, 1500

Fig. 3.1Map of major Florentine convent pharmacies, circa 1584

Fig. 3.2Pharmacy receipts in the hand of Sister Giovanna Ginori, 1567

Fig. 4.1Dominican nun preparing rose unguent, seventeenth century

Fig. 4.2An apothecary instructing an apprentice in his shop, 1505

Fig. 4.3Pharmacy jars depicting the saints John the Baptist and Lawrence, Venice, 1501

Fig. 4.4Pyramid furnace for distillation. Pietro Andrea Mattioli, Del modo di distillare le acque da tutte le piante. Venice, 1604

Fig. 4.5Alessandro Gherardini, Portrait of unknown Florentine nun pharmacist, 1723

The Florentine new year began on March 25, the feast of the Annunciation. Dates given in the text have been modernized to correspond to the calendar year beginning January 1. When citing archival documents in the notes, I give both dating styles when appropriate to avoid confusion.

Renaissance Florentines used a complex monetary system that included silver and gold coins, as well as moneys of account. The lira was a money of account. One lira was divided into twenty soldi; each soldo was subdivided into twelve denari, making a lira equal to 240 denari. In the early sixteenth century, the most common gold coin in circulation was the florin. After the Medici dukes came to power in 1532, the florin was replaced by the scudo or ducato. One scudo was worth seven lire.

ONE OF THE MOST STRIKING FEATURES to emerge from recent studies of Renaissance medicine is the sheer diversity of female practitioners who anchored a wider medical economy. In short, Renaissance women performed much of the day-to-day work of healing and caregiving throughout this period.

Part of the difficulty in integrating these contributions into a broader narrative of early modern medicine stems from the nature of the evidence itself. Much of the documentation for womens medical activities is fragmentary and must be excavated through painstaking work in local archives and obscure print materials. In addition, sources are silent on everyday matters of importance. Birth attendants who worked without compensation or neighborhood women who washed the bodies of the dead have left few traces in the historical record. Because these types of bodywork were thoroughly naturalized as feminine care practices, they entered the historical record only when they rose to the level of visible economic exchange. Complicating matters of evidence still further were collective work-sharing arrangements among family, friends, and neighbors that often make it difficult to know which person was doing exactly what work.

Scholars face an even more vexing problem, however, in trying to conceptualize this diffuse body of evidence. Conventional histories of Renaissance medicine have tended to focus on the transmission of text-based knowledge and institutional authorization by guilds and universities, rather than on healing skills acquired experientially. Our understanding of the interplay and entanglements between female healers and professional medicine as a body of knowledge and practice remains partial at best. A persistent focus on official titles and occupational identities has led us to both undercount and undervalue the healthcare services Renaissance women provided to household and community. Other conceptual challenges stem from coding certain care practices frequently performed by womenfeeding the sick, dressing soresas charitable work, which empties them of medical meaning. The relationship between preventive health measures and much-heralded curative skills also warrants further examination through the lens of gender.

By redefining what constitutes medical work, we can map a more complex terrain for early modern healthcare and womens place in it. New interpretive frameworks have situated women squarely within health promotion and illness management, from pharmacy and household medicine to emerging structures of public health. The terms medical agents and agents of health coined by Monica Green capture a wider range of practitioners active in settings where formal titles were rarely used. Montserrat Cabr has taken a different tack by exploring the overlapping semantic associations between the terms women and healers in late medieval society. The concept of bodywork introduced by Mary Fissell has begun to dismantle some of the hierarchies of value first created in the early modern period and reproduced by later generations. This reorientation results in a more accurate, dynamic depiction of medical provisioning in early modern society while revealing its deeply gendered nature.