iv

COPYRIGHT

2019 University of Hawaii Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

24 23 22 21 20 19 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kim, Sonja M., author.

Title: Imperatives of care : women and medicine in colonial Korea / by Sonja M. Kim.

Other titles: Hawaii studies on Korea.

Description: Honolulu : University of Hawaii Press : Center for Korean Studies, University of Hawaii, [2019] | Series: Hawaii studies on Korea | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018014809 | ISBN 9780824855451 (cloth ; alk. paper), Kindle 9780824855475, EPUB 9780824855468, PDF 9780824855482

Subjects: LCSH: Women in medicineKoreaHistory. | WomenHealth and hygieneKoreaHistory. | Reproductive healthKoreaHistory.

Classification: LCC R692 .K47 2019 | DDC 610.8209519dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018014809

The Center for Korean Studies was established in 1972 to coordinate and develop resources for the study of Korea at the University of Hawaii. Reflecting the diversity of the academic disciplines represented by affiliated members of the university faculty, the Center seeks especially to promote interdisciplinary and intercultural studies. Hawaii Studies on Korea, published jointly by the Center and the University of Hawaii Press, offers a forum for research in the social sciences and humanities pertaining to Korea and its people.

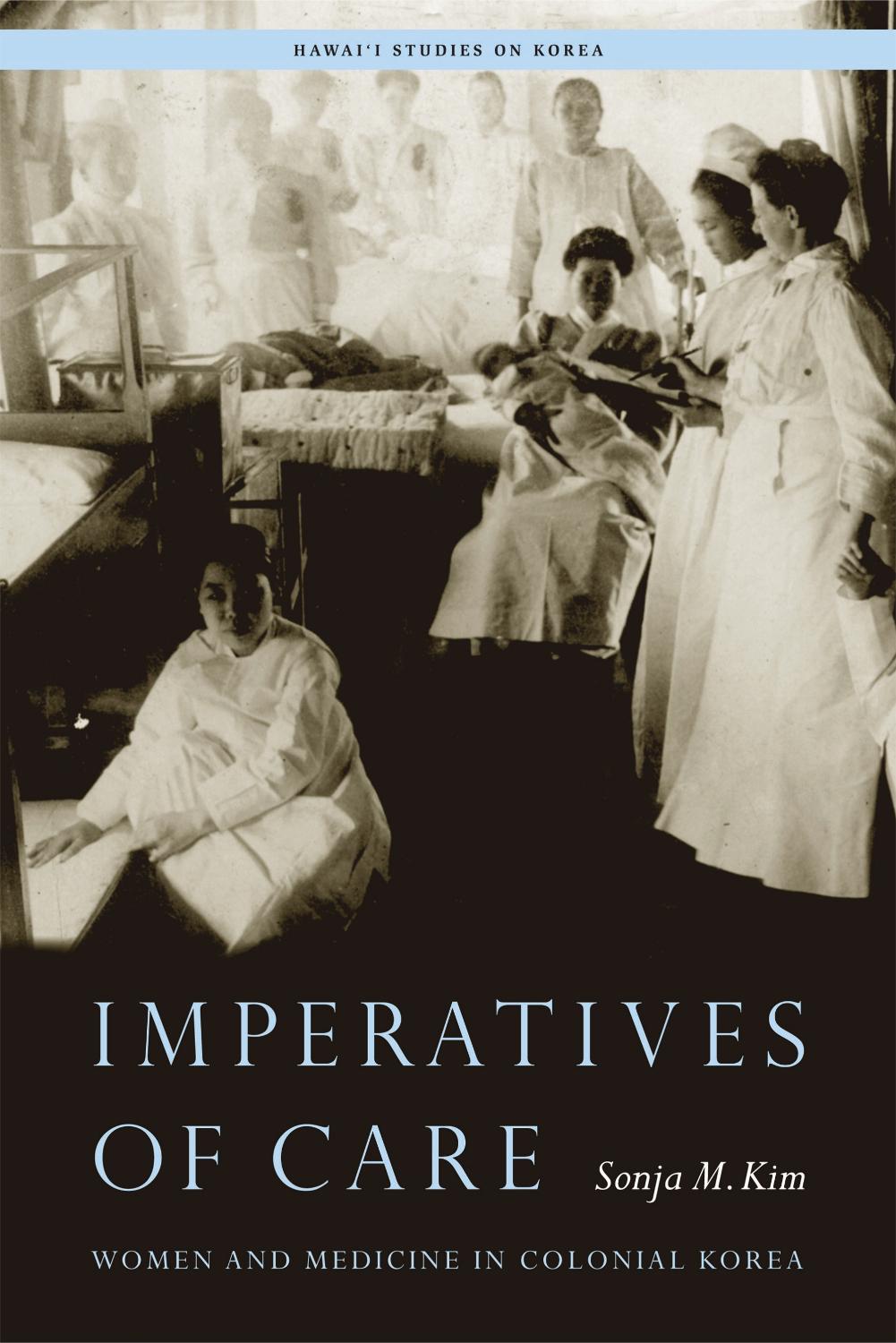

Cover photo: Salvation-for-all-women Hospital (Poguygwan), Seoul, 1907. Photograph courtesy of the United Methodist Church Archives, GCAH, Madison, New Jersey.

University of Hawaii Press books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Council on Library Resources.

vii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

It has been said that writing a book is a labor of love. It is also a humbling experience, intensely challenging mentally, physically, and intellectually. I have been blessed to receive much support and inspiration over the years for which I am deeply grateful.

First, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my professors while a graduate student at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA): John Duncan, George Dutton, Charlotte Furth, Benjamin Elman, Henry Em, Namhee Lee, Gi-Wook Shin, the late Miriam Silverberg, and Sharon Traweek. I also thank Kim Do-hyung, Jung Tae-hern, and the late Pang Kie-Chung for welcoming me in their graduate courses at Korea University and Yonsei University. Their classes, discussions, and examples fostered and continue to shape who I am as a scholar today.

I am also indebted to Yeo Inseok, Park Yunjae, and Sihn Kyuhwan for their continued collegiality and invitation to collaborative study and research at the Department of Medical History at Yonsei University. Conversations with Paul Cha, John Cheng, Hyaeweol Choi, Todd Henry, Kyung Moon Hwang, Jung Keun-Sik, Jennifer Jung-Kim, Michael Kim, Kim Ock-Joo, Kim Tae-Ho, Kwon Bodurae, Robert Ku, Seung-Ah Lee, Yoonkyung Lee, Lim Jongtae, Sung Deuk Oak, Jin-kyung Park, Youngju Ryu, Soyoung Suh, Stella Xu, and Theodore Jun Yoo provided valuable insight and directed me to new questions and sources. The books development also benefited from my engagements with discussants, fellow panel members, and audiences at various venues I presented, including the Annual Meeting of the Association for Asian Studies, the Australian National University, Berkshire Conference on the History of Women, Cornell University, Hamilton College, Korea University, viii University of Hong Kong, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, University of Michigan, University of Toronto, and Yonsei University.

Special thanks are reserved for Su Yun Kim and Leighanne Yuh for their thoughtful reading, Kathy Ragsdale for her incisive editing, and two anonymous readers and my editor Stephanie Chun at the University of Hawai`i Press for their astute suggestions. I also thank my cohorts and classmates at UCLA whose friendship in and outside the classroom sustained me during and after graduate school. Colleagues at my home institution, the State University of New York at Binghamton, welcomed me in their programs, departments, and writing group as well as their homes and lives, furthering my growth as an academic, writer, and human being. My students with their passions and questions remind me daily why I teach and write.

This work was supported by the Core University Program for Korean Studies through the Ministry of Education of Republic of Korea and Korean Studies Promotion Service of the Academy of Korean Studies (AKS-2011-BAA-2103). Other institutions that made the book possible since its early stages include the Committee on Korean Studies of the Northeast Asia CouncilAssociation for Asian Studies, Fulbright-Hays Program, Korea Foundation, UCLA, the Harpur College Deans Office at Binghamton University, and the Fulbright US Scholar Program. I also thank the staff at the General Commission on Archives and History of the United Methodist Church, Presbyterian Historical Archives, Institute of the History of Christianity in Korea, Dong-Eun Medical Museum at Yonsei University College of Medicine, and the rare book collections of Drexel University, Ewha Womans University, Korea University, Seoul National University, UCLA, University of Toronto, and Yonsei University. My gracious hosts in Korea, the Institute of Korean Studies at Yonsei University and Kyujanggak Institute for Korean Studies at Seoul National University, provided me with the space, resources, and community that facilitated my research and writing.

Finally, I thank my relatives in Korea and in-laws in San Francisco for being my home away from home; my parents Myunghee and Kiljung Kim for their unfailing love, my sister Rosanne and my husband Jae for being my rocks; and Milena whose arrival forever shifted my view of history and motherhood. They have sustained me throughout this long journey, and it is to them I dedicate this book.

INTRODUCTION

I n 1899, the vernacular newspaper Cheguk sinmun reported that a young woman, identified only as living in the neighborhood of Pukchon, had approached Chi Sgyng, the principal of the newly opened Government Medical School, asking permission to matriculate. She reasoned, however, that as it remained unclear when that school would open and whether formal education would afford her as a woman (literally, with a female body) the same opportunities as men, she instead should seek medical training, for it would provide her with skills of use to the world on a par with men.

The womans request came during a dynamic period in Koreas history. Internal social strife, new treaty and international relations, and Chinas defeat by Japan in 1895, which signaled the end of the Sinocentric world order on which the Chosn (13921910) kingdoms polity was based, created a profound sense of crisis. Concerned Korean leaders reconceptualized their understanding of civilization and accelerated reform efforts aimed at bolstering Chosns sovereignty. The Cheguk sinmuns praise for this woman incorporated her into an evolving modernist agenda. Her aspirations to acquire education in a newly founded institution and to procure medical expertise lay at the nexus of two key desires of Korean reformers: to improve the health of the population and thus the strength of the polity, and to provide women with skills to contribute to society.