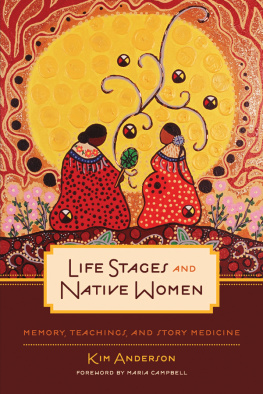

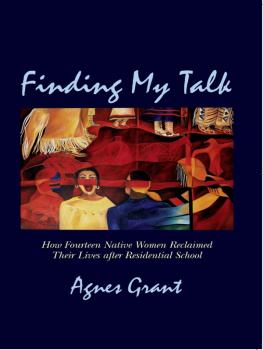

Weaving the Stories

This book represents a weaving together of stories from multiple sources, both written and oral. Whereas the foundation of the book is the oral history that I gathered from the historian participants, I have also used materials that Ive read in books and articles to add depth and context. My aim was to put all of these sources together to build a rich and multilayered story.

Perhaps the most important thing I learned from working on this book is that the process of doing oral history work is as important as what is produced at the end. Whereas the gathering of written sources was a process of collecting information that would develop and support a historical profile of Algonquian women, the process of collecting oral history was much more of an exercise in learning about how story medicines can work, and gradually finding my place within that work. Because this element is so important, I have devoted this chapter and the next to describing the sources I drew from, the process it involved, and how I wove it all together. I begin with a quick glance at the written sources before getting into considerations about Indigenous oral history.

Written Sources

Although there is very little in terms of focused literature on life stages of Native women, it was possible to glean some information by combing through many different sources, disciplines, and literary genres.

I began with the history books, but soon found that in spite of the increasing production of womens history since the 1970s, the lives of Indigenous women are still largely invisible in that genre of literature. There are some exemplary historians who have written about Algonquian womens lives in the fur trade era and up into the nineteenth century,

If you are looking for information about these distinct Indigenous worlds, it would be better for you to go to the ethnographic and autobiographical literature. Although the earliest autobiographical works that cover the pre-reserve and early settlement period are written by men, one can mine them for information about womens lives.

Ethnographies offer the most explicit sources of information about the life cycle of Algonquian women, especially those that were researched and written during the early twentieth century. Many of these stories can be historically situated within the late pre-reserve and early reserve era.

I was able to find a fair amount of information in the ethnographic material related to the work that women did in land-based societies, and these depictions of womens work provided a backdrop for writing about middle-aged women. There was also a fair amount of information in the ethnographic literature related to marriage, family structure, and kinship obligations, and there was some information about the roles of older women. These roles included working as herbalists and midwives, looking after children and being teachers of the younger generations. Information about children often focused on their contributions to community in terms of work and child-rearing practices and styles. I was surprised to find that there was also plenty of information in the ethnographic material about ceremonies for infants and girls, particularly naming ceremonies and puberty rites. After years of yearning for more information about these ceremonies, I realized that there are descriptions in the ethnographic literature! Of course, there are people who carry this knowledge and continue to do the ceremonies, but documentary information can be helpful and perhaps more accessible to those who dont have teachers in their own circles.

My review of all this material reinforced what Maria Campbell has encouraged me to do in terms of working with literature. As Maria describes in her preface to this book, the late Anishinaabe Elder Peter OChiese always stressed to her how important it is for Indigenous people to sift though ethnographic literature because it can be helpful to us as we put the pieces of our cultures back together. The message is to read as much as you can, while being aware of the limitations. I always bear in mind the lesson from my friend the Sto:lo Elder and healer Dorris Peters, who remembers her uncles telling the craziest stories that they made up on the spot to have fun with the anthropologists who came around in the 1930s! For this reason, it is important that we work with our elders and oral historians at the same time as we read the literature. As I demonstrate in the next section, this work with oral history involves much more than collating information and checking for facts. It is about working with story medicines.

Purpose: Listening for Stories that Work like Arrows

Clearly, Indigenous oral histories do not abide by conventional disciplinary boundaries. They are about relationships and generational continuity, and the package is holisticthey include religious teachings, metaphysical links, cultural insights, history, linguistic structures, literary and aesthetic form, and Indigenous truths. Winona Wheeler, Decolonizing Tribal Histories

As Winona Wheeler indicates, Indigenous oral history contains many elements that take it beyond the goal of showing how it was. There is often an overt sense of purpose to oral history work, and this book is definitely built on that element. I share my sense of purpose with a number of other Indigenous scholars who have framed the writing of Indigenous history as a project in decolonization. According to this approach, oral history serves our communities by providing insight and vision and inspiring change for the better.

In addition to providing insight and vision, one of the primary characteristics of Indigenous oral history is to delineate the world view of the people it serves. The truths we seek in this work are thus more about the truths of who we are and want to be as a people, rather than the truths about what happened.

Whereas academic historians may be reluctant to engage in this kind of history-telling, anthropologists have been recognized and rewarded for their Indigenous oral history work. Anthropologist Julie Cruikshank is often cited for the work that she has done with Elders Angela Sidney, Kitty Smith, and Annie Ned in the Yukon. Cruikshank has written about how she originally went looking for narratives about events (in particular, how the Klondike gold rush affected womens lives) and was confounded when Elders provided traditional stories instead. She later realized that the Elders allegorical stories underpinned the narratives and events of their own lives. Their traditional stories provided a code by which one could live a good life, a life lived like a story.

In the field of linguistic and cultural anthropology, Keith Basso has been recognized for his award-winning books that explore this function of story among the Apache. Basso has documented how Apache stories often work like arrows, acting as piercing missives, sent out to make you live right.

I offer these considerations because, as a historian working with Indigenous oral history on this project, my aim has been to foster healing and decolonization by delineating a world view and creating a sense of identity and belonging. Judging from the standards of conventional history, some might find both the individuals stories and my overarching narrative too idyllic. But one must bear in mind that my intent was to create a story that works like an arrow, What I have provided for the reader are glimpses and threads of a world in which identity and belonging were fostered and nurtured in childhood; where women had authorities that were rooted in cultures that valued and respected equity; and in which old ladies ruled. The reader will not find stories of violence and abuse here, although these things were also happening in northern Algonquian communities from the 1930s to the 1960s. There are other works that tell stories of domestic violence, fallout from residential schools, and communities in crisis. Although such works are important to consider for the truths they tell, this is not the focus of the stories in this book.