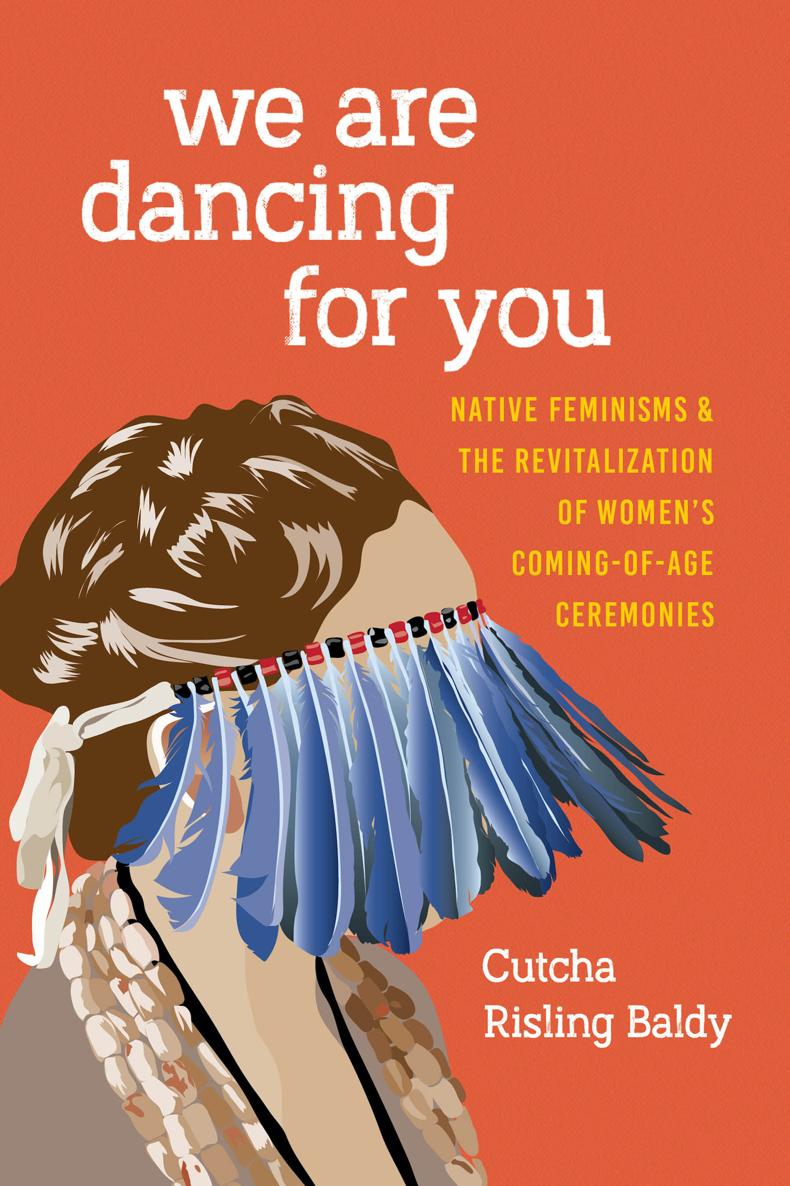

| We Are Dancing for You was supported by a grant from the Tulalip Tribes Charitable Fund, which provides the opportunity for a sustainable and healthy community for all. |

Copyright 2018 by the University of Washington Press

Printed and bound in the United States of America

Composed in Charter, typeface designed by Matthew Carter

22 21 20 19185 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

University of Washington Press

www.washington.edu/uwpress

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data on file

ISBN 978-0-295-74343-1 (hardcover), ISBN 978-0-295-74344-8 (pbk),

ISBN 978-0-295-74345-5 (ebook)

Parts of .

Cover illustration by Katrina Noble, from a photograph taken by Cutcha Risling Baldy.

Thank you to Dentilla Albers for inspiring the image.

PREFACE

The Flower Dance is a dance that I wish all young women could haveall Hupa women, Yurok women, Karuk women, everyone. Its not only important for the young woman but its important for her family, and the community, and our belief system to have this ceremony. [This dance] does heal. That kind of intensive trauma where women have been abused and mutilated both spiritually and emotionally and physically. I think it does. I know it does. You are being celebrated as opposed to being demonized or looked down upon. This dance comes along and says, I think enough about you that Im going to, for ten days or five days, or whatever it is, Im going to sing over you every night. Im going to make sure that you have a good experience. Thats very, very positive. Thats very important, that I think youre worth that.

Lois Risling (Hupa, Karuk, Yurokand my mom)

This book begins and ends with my mother. Lois Risling is a strong, powerful, often larger-than-life woman, the kind you wish you could be, or maybe are glad that you dont have to be. The things my mother said to me growing up have stuck with me as I navigated through the many life stages of being a Native woman in todays society. My mother was there when I checked in for my first day of college, and she helped move me into my first apartment (when, true story, she hoisted a couch over the second-floor balcony when it wouldnt fit through my door); she was there when I got married, and she was there when I gave birth. I am the first to admit that we did not get along well when I was in high school. I relied a lot on my father, Steve Baldy, as a mediator because he loved both of us and tried his best to help us get along. When I was in college I often ignored my mothers phone calls because I was convinced shed only called to tell me something that I hadnt gotten done from the long list of things you should be getting done when you are an adult. But sometime in my early twenties we began to talk more, and at some point I started calling her my friend. Once I was interviewing for a job and the interviewer asked me, What is your greatest accomplishment in life? I paused before I said to him, Learning to be friends with my mother. He told me it was the best answer hed ever gotten to that question.

Growing up, I did not and most likely couldnt have understood the inherent exhaustion of raising a young Native woman in this contemporary settler colonial culture and society. I remember trying to convince my mother that Columbus discovered America for Europeans, which had to count for something, right? In the fourth grade when we were learning about the missions, she insisted on coming to my classroom to teach students about California Indian history. My grandmother came with her and we fed everyone salmon and acorns. In the seventh grade I started to cry every time she made me get in the car to go to a ceremony. This was mostly because I wanted to stay home and be normal and also because I was in love with the boy across the street and just wanted to sit outside and talk to him all day.

When I was twelve I started menstruating, and my mother insisted on taking me out to dinner to celebrate. We went to a really fancy restaurant, which I knew was fancy because they served Bananas Foster right at your table. Our waiters name was Gary. Ill never forget it. And after he was done taking our orders, he asked my mother, Are we celebrating anything today? I was paralyzed. In my mind my mother was not only going to tell Gary all about my newfound womanhood, she was also going to pull a bunch of tampons out of her purse and throw them at me while yelling, Congratulations on your period! Gary waited patiently until my mother said, No, no. We are just a mother and daughter having a nice evening together. I was safe. For the moment.

During dinner my mother told me about the Hupa womens coming-of-age ceremony. She said, In the old days, we would have done a Flower Dance for you. The Hupa used to celebrate this time. It was very important to us, when girls became women. We could do a dance for you now, if youd like. I wish I had known at the time what she was offering. I wish I had known that the dance had not been performed for many years. At one time the Flower Dance was a principal dance of our tribe, but after the destruction and genocide of the Gold Rush era, the influence of the boarding school, policies enforced by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the missionaries, and other lasting traumas of colonization, the Flower Dance was very rarely practiced, no longer the public celebration it had once been.

Many of our ceremonies had survived. The Native peoples of Northwestern California have a historical narrative where many scholars note that this region was relatively late in being contacted by Western settlers. The Hupa people fought very hard to keep their ceremonies and ways of knowledge and are one of only a handful of Native peoples who still live on their Indigenous land base where old stories say our people came into being. The Hupa (as well as the surrounding Yurok and Karuk) come together for Brush Dances (to heal or bless a child), White Deerskin Dances, and Jump Dances. The Hupa consider the White Deerskin Dance and the Jump Dance to be high dances. These are the dances that are done for all time in the Kixinay world. It is only when we call the dance to us that the Kixinay stop these high dances so we can do them on earth. The social-spiritual enactment of these practices was responsible for keeping the earth in balance and society thriving. During some of the harshest policies set forth to destroy Indian societies by specifically attacking Indian spirituality and religion, the Hupa were steadfast in their continuance of the dances.