THE HEALTHY ANCESTOR

Advances in Critical Medical Anthropology

Series Editors: Merrill Singer and Pamela Erickson

This book series significantly advances our understanding of the complex and rapidly changing landscape of health, disease, and treatment around the world with original and innovative books in the spirit of Critical Medical Anthropology that exemplify and extend its theoretical and empirical dimensions. Books in the series address topics across the broad range of subjects addressed by medical anthropologists and other scholars and practitioners working at the intersections of social science and medicine.

Volume 1

Global Warming and the Political Ecology of Health: Emerging Crises and Systemic Solutions, Hans Baer and Merrill Singer

Volume 2

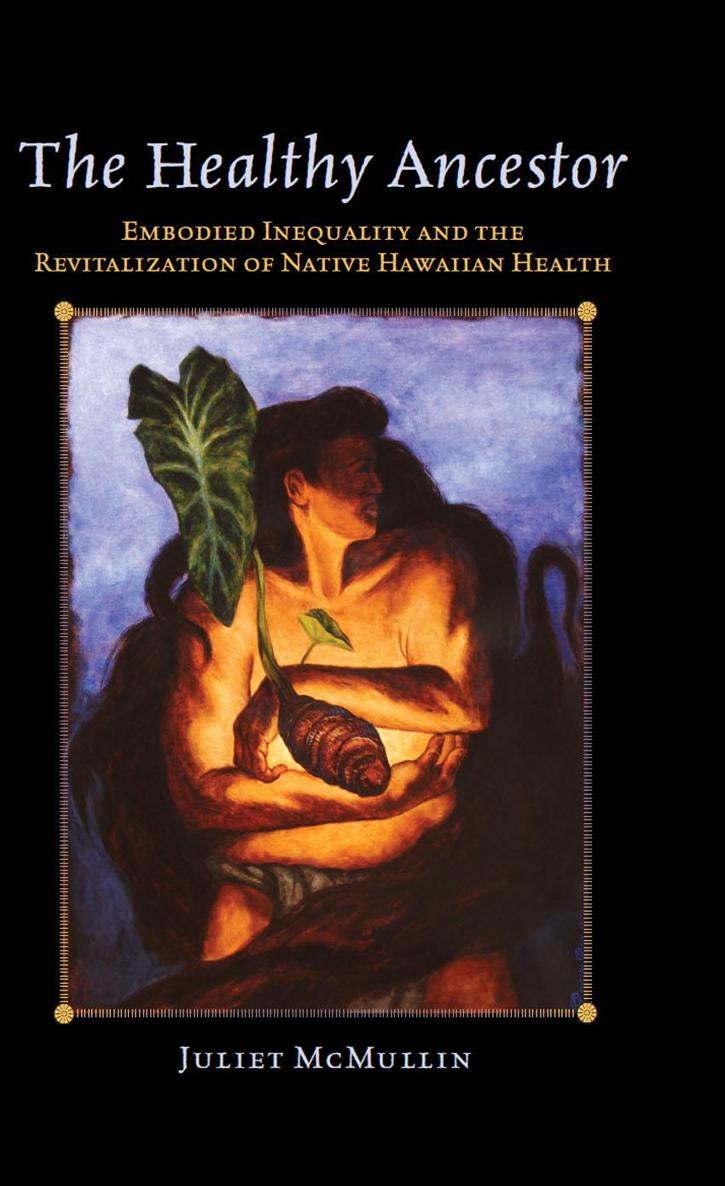

The Healthy Ancestor: Embodied Inequality and the Revitalization of Native Hawaiian Health, Juliet McMullin

THE HEALTHY ANCESTOR

Embodied Inequality and the Revitalization of Native Hawaiian Health

Juliet McMullin

First published 2010 by Left Coast Press, Inc.

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2010 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

McMullin, Juliet Marie.

The healthy ancestor : embodied inequality and the revitalization of native hawaiian health / Juliet McMullin.

p. cm.(Advances in critical medical anthropology)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-59874-499-6 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Medical anthropologyHawaii. 2. Public healthHawaii. 3. Traditional medicineHawaii. 4. HawaiiansHealth and hygiene. 5. HawaiiansMedical care. 6. HawaiiansEthnic identity. 7. Body, HumanSocial aspectsHawaii. I. Title.

GN296.5.U6M35 2009

306.46109969dc22

2009028844

Cover design by Piper Wallis.

Cover illustration The Kalo by Cameron Chun, pthaloblue.com

Hardback ISBN 978-1-59874-499-6

CONTENTS

When I arrived in Hawaii in the mid-1990s to begin fieldwork, my original intent was to understand Native Hawaiian knowledge of cancer and specifically of breast cancer risks. At the time, Native Hawaiian women had some of the highest rates of breast cancer in the United States. The proposed work would be an extension of my work on cancer disparities among Latinas and, on a personal note, it would give me an opportunity to learn about my family who were from the islands. As I began talking with Native Hawaiian women and men I found that many were willing to share their stories of loved ones who had experienced and then passed away from cancer. What was of more interest to the people I spoke with, and the friends I made along the way, was their overall view of Hawaiian health. They were interested in how health was impacted by their lack of sovereignty and access to land and traditional healthy foods. This book is an effort to describe what Native Hawaiians told me about their health and the politics of health. It is my analysis of how Native Hawaiians describe the former and the continuing unraveling of their physical and cultural health by those who promote social structures that value dismembering social relationships and promote individual responsibility as the sole course of action. More importantly, it is a description of how on-island and off-island Native Hawaiians remember their ancestors through meanings of health and practices that reintegrate relationships with the ina and with each other. The practices associated with health and remembering are political statements against the inequities Native Hawaiians have suffered as well as a charter for their own views on how to be healthy and overcome cultural, political, and health inequalities.

There are two issues on language that should be clarified. The first is the use of the term Native Hawaiian as an ethnic identifier. There have been numerous terms used for this group: Hawaiian, native Hawaiian, Native Hawaiian, Kanaka Maoli, and Kanaka Oiwi. Silva (2004) and Kauanui (2008) have shown the historical and political use of these terms. For instance, native Hawaiian is used by the Federal Government to describe individuals who have a blood quantum of at least 50 percent Hawaiian ancestry to pre-contact Hawaiians (Hawaiians who lived on the islands prior to Captain Cooks arrival in 1778) (Kauanui 2008). In contrast, Native Hawaiian is used to signify any blood relationship to pre-contact Hawaiians. More recently, members of Hawaiian sovereignty and revitalization movements have used Kanaka Maoli, meaning real people to identify Native Hawaiians (e.g., Kameeleihiwa 1992; Blaisdell 1993; Trask 1993; Gomes 1994). I have used all the terms to signify any individual with ancestry that traces back to pre-contact Hawaiians. The second note on language is the use of Hawaiian words. Following the lead of Native Hawaiian scholars (Silva 2004; Kauanui 2008), Hawaiian words are not italicized and definitions are provided at the first use of a word.

I am forever grateful to all the acquaintances, friends, mentors, and colleagues who provided endless encouragement in getting this book to publication. First and foremost are the people who generously shared their time and knowledge with me. I hope my understanding of your mnao is worthy of your care for me. Among those individuals is Carolyn Kualii who prompted me to begin this work and guided me throughout the process. To Clarence Kahana and Dorothy Kauahi who so generously opened their home to my daughter and me, we will always remember you as family. To Virginia and Angie who assisted with some of the interviews. Mahalo to, Kamuela Senior Center, Na Mamo, Hui No Ka Ola Pono and Kaanapali Hotel who were supportive of this effort. And to Cameron Chun whose artwork captured so many of the ideas I have tried to convey and who graciously allowed me to use The Kalo for the book cover. To my academic mentors Leo Chavez, Mike Burton, Art Rubel, Karen Leonard, and Carol Browner: thank you for reading numerous drafts as data was being collected and ideas were in their infancy. The Department of Social Relations at University of California, Irvine provided summer funding. My colleagues at the University of California, Riverside have been immensely supportive in the final effort to complete the manuscript. In particular, Tom Patterson for his gentle yet persistent questioning and encouragement during the different stages of theorizing and editing; Chikako Takeshita, Jennifer Heung, Sally Ness, Christina Schwenkel, and Amalia Cabezas were a sounding board for many thoughts about place and identity. To my haumana, Laurette McGuire, Lisa Garibaldi, and Amy Dao who read, critiqued, and assisted with obtaining images; you make teaching and learning so much fun. Merrill Singer and Pamela Erikson, editors of the Advances in Critical Medical Anthropology series at Left Coast Press, thank you for helping frame the book in a literature that finally made me let go; your questions and insights have been invaluable. Jennifer Collier, I am grateful for your encouragement, patience, and help through the whole publishing process.