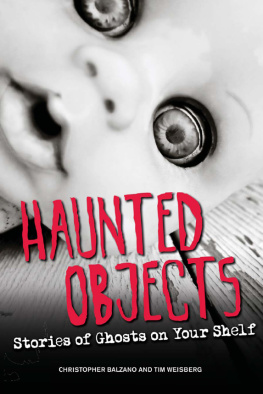

HAUNTED OBJECTS

Literature and Cultures Series

General Editor : Greg Dawes

Series Editor : Ana Forcinito

Copyeditor : Audrey Hansen

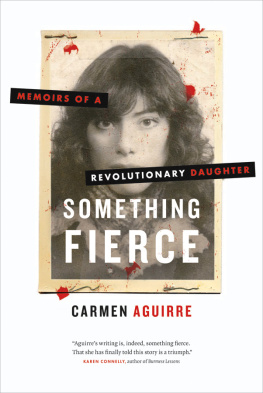

Haunted Objects

Spectral Testimony in the Southern Cone Post-Dictatorship

Megan Corbin

Raleigh, North Carolina

2021 Megan Corbin

All rights reserved for this edition copyright

2021 Editorial A Contracorriente

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Corbin, Megan, author.

Title: Haunted objects : spectral testimony in the Southern Cone post-dictatorship / Megan Corbin.

Other titles: Literature and cultures series.

Description: [Raleigh] : Editorial A Contracorriente, 2021. | Series: Literature and cultures series | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020048517 | ISBN 9781469664293 (paperback) | ISBN 9781469664309 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Disappeared personsSouthern Cone of South America. | Personal belongingsSouthern Cone of South America. | Material cultureSouthern Cone of South America. | Political prisonersSouthern Cone of South America. | Collective memorySouthern Cone of South America. | Victims of state-sponsored terrorismSouthern Cone of South America. | Prisoners as artists--Southern Cone of South America.

Classification: LCC HV6322.3.S63 C67 2021 | DDC 362.87098dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020048517

ISBN: 978-1-4696-6429-3 (paperback)

ISBN: 978-1-4696-6430-9 (ebook)

This is a publication of the Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures at North Carolina State University. For more information visit https://uncpress.org/books/?publisher=editorial-a-contracorriente

Distributed by the University of North Carolina Press

www.uncpress.org

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

As I reflect back on the ten years that led to the publication of this project, the words thank you seem profoundly inadequate to express the gratitude I feel toward all those who contributed to its completion. This book began as my doctoral dissertation at the University of Minnesota, where I spent ten years studying as an undergraduate and graduate student. Early in my studies there, Ren Jara opened my eyes to the power of literature and, in so doing, changed my path from one headed toward law school to one focused on studying testimonio and human rights. I am thankful for the support of all of the faculty with whom I took courses; without their multidisciplinary perspectives the books theoretical framework would not exist. I want to particularly thank Amy Kaminsky, Ofelia Ferrn, and Nicholas Spadaccini for their comments.

I have been very fortunate, dare I say extremely lucky, to have Ana Forcinito as a mentor throughout the course of this project. I am grateful to her for having confidence in me when I was a graduate student and letting me run with the idea of analyzing objects in testimonial textsI will never forget her comment early on that she saw I was thinking about something and to just keep thinking. Her support, especially during the last year of my graduate career, went above and beyond that which can be expected of an advisor and for that I am more appreciative than words can express. I hope that I can act in the same capacity for my own students one day.

I am very grateful to Alberto Ribas Casasayas and Amanda Petersen for organizing a panel at the American Comparative Literature Associations Spring 2012 conference where I received a number of comments and suggestions on an initial version of the main theoretical argument that informs this project. I am also grateful to Stacey Schlau for her mentorship on putting together a book proposal, to Jason Bartles for always sharing his perspective on the process, and to all my colleagues at West Chester University whose support in various ways helped me navigate finishing this manuscript while teaching four classes a semester.

A special thank you to all who shared their stories with me, revisiting what have to be painful memories in order to contribute to the building of this project. In Chile, thank you to Vernica Snchez at the Museum of Memory and to Anah Moya Fuentes, Jos Danor Moya Paiva, Maria Alicia Salinas, and Marcela Andrades lfaro for helping me find information about the artesanas carcelarias that I could not have found on my own. In Montevideo, thank you to those at Crysol, as well as Antonia Yaez, Pedro Giudice, and Stela Reyes who invited me into their homes for conversation and to view and photograph the craftwork that they kept from their time in the political prisons.

The research for this project was made possible by the generosity of the College of Liberal Arts at the University of Minnesota, which granted me a fellowship that allowed me to travel to Chile, Argentina, and Uruguay and to discover much of the information that now forms the basis of this study. During that summer, I was generously welcomed into the homes of a number of individuals who helped me navigate the cities where I conducted my research. Mara Eugenia, Sebastin, Beln, Guadalupe, Patricia, Elena, Sal, Marili and Alexis, Fernando, Mariana, Zoraya, Johan, and Sairathank you all for opening your homes to me, and to Sebastin, a special thank you for giving up easy access to your toys and lending me your room for a month in Santiago. In addition to that funding, a Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship for the academic year of 20132014 gave me the time to immerse myself completely in the project. Additionally, the support of the College of Arts and Humanities at West Chester University allowed me to make subsequent trips to each country to refine my understanding of the sites of memory and incorporate more pinpointed examples into the books argument. I also want to thank the Office of Research and Creative Activities at WCU for supporting production costs for the book.

Thank you to my family for their constant support, to my husband, Michael, for his patience with my propensity to put work before all else, and a special thank you to my son, Corbin Michael, whose impending arrival was just the push I needed to finally finish revising. Thank you for waiting until all the writing tasks on the baby list were completed to make your entrance into this world.

CONTENTS

PART ONE

SUBJECT/OBJECT RELATIONS DURING DETENTION

PART TWO

TOWARD A TESTIMONIAL THEORY OF OBJECTS

INTRODUCTION

The Absent Witness The Enduring Material

Skeleton #33: We find signs that it was a woman.

A hair pin.

A bra.

It is harder to find these objects associated with the skeletons than it is to uncover the remains.

We have always lived off the splendor of the subject and the poverty of the object.

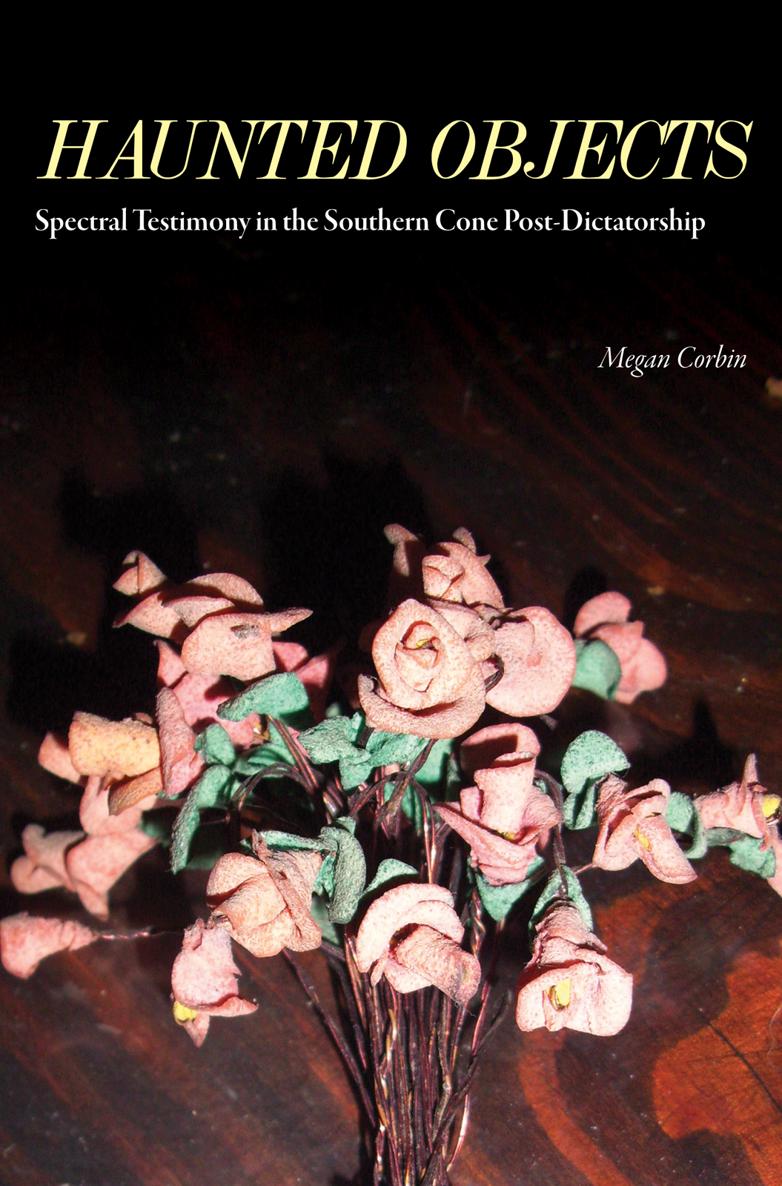

I N THE FAR-RIGHT CORNER of the Parque por la Paz (Park for Peace), the former space of the Villa Grimaldi/Cuartel Terranova detention center in Chile, there remains a seemingly inconsequential tree. One of many on the grounds, it stands largely hidden by the grandiose monument of names, built in homage to those who disappeared from the grounds of the center. This tree is easy to pass by without notice. There are no markers in this area of the park to signal to the visitor a special significance, the area stands at a distance from the rest of the grounds, a mere alternative path to pass through on the way to the next stop of the guided audio visit. However, if one looks up into the branches of the tree, they will see a loop of barbed wire that hangs around one of the branches and may wonder if it is a quiet, yet lasting testament to the atrocities of a space that was meant to be destroyed and forgotten forever [Image 1].