Barakaldo Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

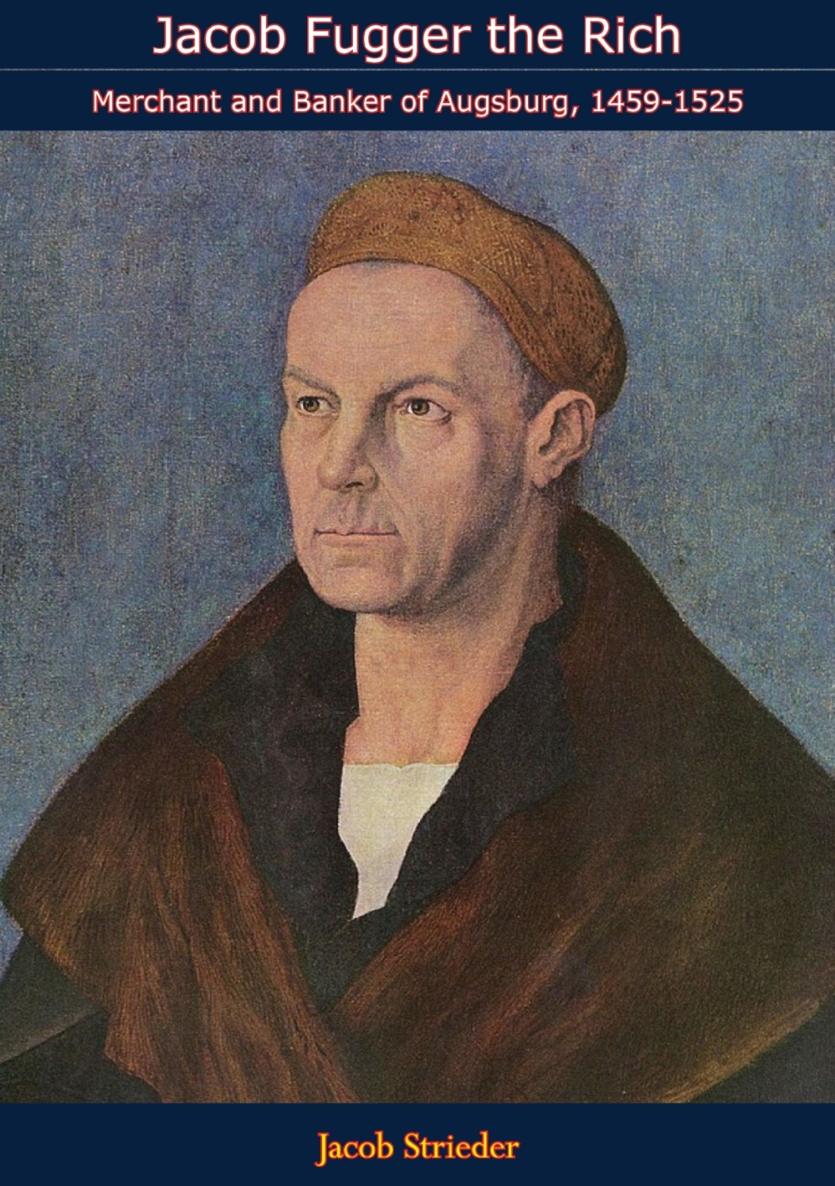

JACOB FUGGER THE RICH

MERCHANT AND BANKER OF AUGSBURG, 1459-1525

BY

JACOB STRIEDER

TRANSLATED BY

Mildred L. Hartsough

EDITED BY

N. S. B. Gras

EDITORS INTRODUCTION

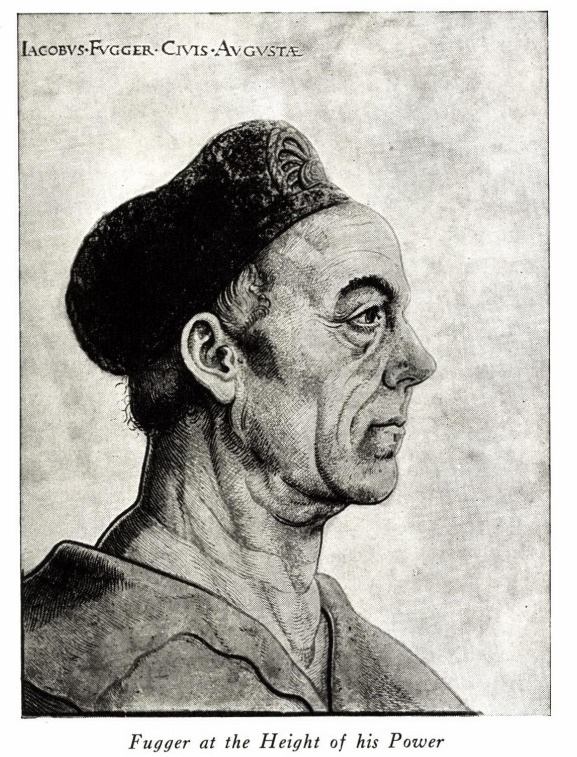

Jacob Fugger is a splendid example of the successful merchant who flourished shortly after the discovery of America. The biography of Fugger by Professor Strieder is also a fine example of the work done by economic historians in the field that is becoming specialized as business history. Other economic historians who have been interested in the business man are Ehrenberg and Sombart in Germany, Se in France, and Unwin in England.

The present book and others by the same author are helping to lay the foundations for business history. The study of economic history has become so well developed that no one can comprehend it all. Those who wish to make progress in the field actually specialize in some part of itfinancial, commercial, industrial, or agricultural history, or the history of economic regulation, or the history of prices, wages, rent, and income. It may be a matter of lingering regret that subjects and disciplines are being so split up, but it is also a matter of congratulation, because intelligent specialization means progress in the discovery of facts and in the formulation of generalizations.

In the early history of the business of getting a living no step was more important than the development of a class of entrepreneurs. A middle class of profit-takers came upon the scene to rival and often to command princes, ecclesiastics, nobles, artisans, and peasants. The coming of this class was, of course, unplanned. As the noble found his setting in the castle, the peasant in the field, and the cleric in the pulpit, so did the business man flourish in the town. There protection could be found, special services were available, and a system of economic regulation could be worked out favorable to trade.

Today we accept the business man, large and small, as part of our civilization; and nowhere is this more true than in America. But historically we must account for him: he has arrived late upon the scene. In each great epoch of civilization he has come with the town and in all but ours he has gone down with the town.

A social class is a bundle of habits and attitudes, a multicolored pattern of ways of doing things and of values in life. The business man was foresighted, continuously active, rational rather than emotional in his attitudes, saving his income for further investment, diversifying these investments, and risking his capital for the sake of profits. That the buying and selling of goods and credit came at times to be an end in itself is to be expected.

Just what forces were at work to create such a class of business men and such an individual as Fugger is a problem not easy to decide. It has been thought that Judaism and Calvinism were influential while Catholicism was not helpful in the creation of a spirit of enterprise. Certainly the Jews and the Scots have been excellent business men, as also Baptists and Presbyterians. The Huguenots in France and the Puritans in New England were hard workers and successful artisans and traders. Jacob Fugger was a Catholic and also a great merchant, but a large part of his success in business was due to his breaking away from the Churchs attitude to interest and just price. In fact, he may be regarded as one of the forces within the Church that led to a reformed Catholic attitude to business.

Much more important than religion is the existence of individualism and initiative among men, founded upon deep psychological considerations. Individualism was in no sense new when the medieval town was developing: it had existed in the person of the marauding leader of a pillaging band and in religious leaders and saints. But at last there was opportunity for commanding leadership on a large scale and on a peaceful and rational basis. The trade within towns and between towns and fairs was the favorable setting for the business mans birth. It was partly the cause and partly the result of his activity, just as Augsburg was partly the cause and partly the result of the life and work of Jacob Fugger.

The use of money and the bill of exchange was necessary to business success, as were many other things such as a business ethics, bookkeeping, and a development of the applied arts. In the affairs of Jacob Fugger we find many coins in use, the most prominent in commercial reckoning being the gold gulden.

Although the gold or Rhenish gulden varied in weight and fineness from time to time, it was roughly equivalent to the English pound sterling about the year 1500. The English pound would have purchased about 25 bushels of the best wheat at the same time. Since wheat is worth about $1.00 a bushel (? 1930), we can say that the purchasing power of the gold gulden, reckoned in terms of the best American wheat, would be about $25.00. Accordingly, it would not be far wrong to multiply by 25 the various figures that are expressed in gold gulden in the chapters that follow, in order to get the equivalent in American dollars. Of course, any such statement as this, based upon consideration of the price of only one commodity, may be far from satisfactory in general application.

The form of business combination used by the Fuggers was the family partnership. This, along with the temporary partnership which developed in Genoa, was an important link in the chain which led from the individual business man to the joint-stock company and finally the corporation holding various other corporations together. The great problems in family partnership were to provide for continuity of effort and capacity in management. Jacob Fugger was insistent upon both. The outstanding modern instance of a family partnership is the Rothschilds. A notable instance nearer home is the Straus brothers of the R. H. Macy & Company, Inc., New York, who, although they now operate under a corporate form, have been essentially a family partnership.

The business of the Fuggers was centralized in the home office at Augsburg, but somewhat localized in such distant points as Naples and Antwerp. The Fugger inventory of 1527 illustrates the wide-flung nature of the business in which the partners of Augsburg were engaged. When the family partners or the partners and their children were numerous and capable, there were plenty of satisfactory district managers, as we should say. But otherwise there must have been a trying problem to find men of ability and integrity to occupy subordinate positions of such importance.