PREFACE.

The publication in 1814 of a voyage commenced in 1801, and of which all the essential parts were concluded within three years, requires some explanation. Shipwreck and a long imprisonment prevented my arrival in England until the latter end of 1810; much had then been done to forward the account, and the charts in particular were nearly prepared for the engraver; but it was desirable that the astronomical observations, upon which so much depended, should undergo a re-calculation, and the lunar distances have the advantage of being compared with the observations made at the same time at Greenwich; and in July 1811, the necessary authority was obtained from the Board of Longitude. A considerable delay hence arose, and it was prolonged by the Greenwich observations being found to differ so much from the calculated places of the sun and moon, given in the Nautical Almanacks of 1801, 2 and 3, as to make considerable alterations in the longitudes of places settled during the voyage; and a reconstruction of all the charts becoming thence indispensable to accuracy, I wished also to employ in it corrections of another kind, which before had been adopted only in some particular instances.

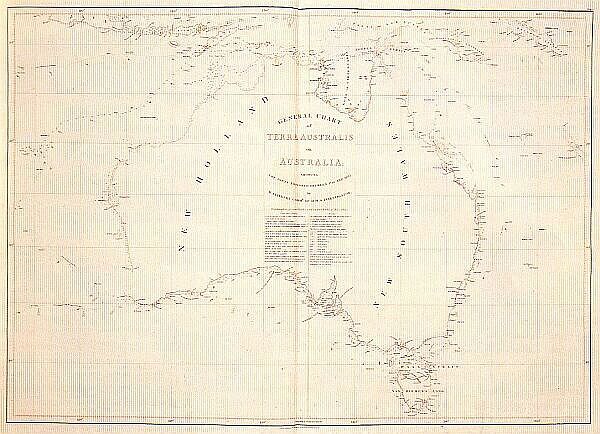

A variety of observations with the compass had shown the magnetic needle to differ from itself sometimes as much as six, and even seven degrees, in or very near the same place, and the differences appeared to be subject to regular laws; but it was so extraordinary in the present advanced state of navigation, that they should not have been before discovered and a mode of preventing or correcting them ascertained, that my deductions, and almost the facts were distrusted; and in the first construction of the charts I had feared to deviate much from the usual practice. Application was now made to the Admiralty for experiments to be tried with the compass on board different ships; and the results in five cases being conformable to one of the three laws before deduced, which alone was susceptible of proof in England, the whole were adopted without reserve, and the variations and bearings taken throughout the voyage underwent a systematic correction. From these causes the reconstruction of the charts could not be commenced before 1813, which, when the extent of them is considered, will explain why the publication did not take place sooner; but it is hoped that the advantage in point of accuracy will amply compensate the delay.

Besides correcting the lunar distances and the variations and bearings, there are some other particulars, both in the account of the voyage and in the Atlas, where the practice of former navigators has not been strictly followed. Latitudes, longitudes, and bearings, so important to the seaman and uninteresting to the general reader, have hitherto been interwoven in the text; they are here commonly separated from it, by which the one will be enabled to find them more readily, and the other perceive at a glance what may be passed. I heard it declared that a man who published a quarto volume without an index ought to be set in the pillory, and being unwilling to incur the full rigour of this sentence, a running title has been affixed to all the pages; on one side is expressed the country or coast, and on the opposite the particular part where the ship is at anchor or which is the immediate subject of examination; this, it is hoped, will answer the main purpose of an index, without swelling the volumes. Longitude is one of the most essential, but at the same time least certain data in hydrography; the man of science therefore requires something more than the general result of observations before giving his unqualified assent to their accuracy, and the progress of knowledge has of late been such, that a commander now wishes to know the foundation upon which he is to rest his confidence and the safety of his ship; to comply with this laudable desire, the particular results of the observations by which the most important points on each coast are fixed in longitude, as also the means used to obtain them, are given at the end of the volume wherein that coast is described., as being there of most easy reference.

The deviations in the Atlas from former practice, or rather the additional marks used, are intended to make the charts contain as full a journal of the voyage as can be conveyed in this form; a chart is the seaman's great, and often sole guide, and if the information in it can be rendered more complete without introducing confusion, the advantage will be admitted by those who are not opposers of all improvement. In closely following a track laid down upon a chart, seamen often run at night, unsuspicious of danger if none be marked; but some parts of that track were run in the night also, and there may consequently be rocks or shoals, as near even as half a mile, which might prove fatal to them; it therefore seems proper that night tracks should be distinguished from those of the day, and they are so in this Atlas, I believe, for the first time. A distinction is made between the situations at noon where the latitude was observed, and those in which none could be obtained; and the positions fixed in longitude by the time keepers are also marked in the track, as are the few points where a latitude was obtained from the moon.

It has appeared to me, that to show the direction and strength of the winds, with the kind of weather we had when running along these coasts, would be an useful addition to the charts; not only as it would enable those who may navigate by them alone to form a judgment of what is to be expected at the same season, but also that it may be seen how far circumstances prevented several parts of the coast being laid down so correctly as others. This has been done by single arrows, wherever they could be marked without confusion; they are more or less feathered, proportionate to the strength of wind intended to be expressed, and the arrows themselves give the direction. Under each is a short or abridged word, denoting the weather; when this weather prevailed in a more than usual degree a line is drawn under the word, and when in an excessive degree there are two lines. Single arrows being thus appropriated to the winds, the tides and currents are shown by double arrows, between which is usually marked the rate per hour.

On the land, the shading of the hills gives a general idea of their elevation, and it has been assisted by saying how far particular hills and capes are visible from a ship's deck in fine weather; this will be useful to a seaman on first making the land, be a better criterion to judge of its height, and those hills not so marked may be more nearly estimated by comparison. Behind different parts of the coast is given a short description of their appearance, which it is conceived will be gratifying to scientific, and useful to professional men. The capes and hills whose positions are fixed by cross bearings taken on shore or from well ascertained points in the track, as also the stations whence bearings were observed with a theodolite, have distinguishing marks; which, with all others not before in common use, are explained on the General Chart, Plate I.