The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd.., London

1977 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 1977

Phoenix edition 1980

Printed in the United States of America

07 06 05 04 03 02 01 00 99 98 7 8 9 10 11

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-15033-8 (e-book)

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Gregor, Thomas.

Mehinaku: the drama of daily life in a Brazilian Indian village.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

2. Mehinaku IndiansSocial life and customs. I. Title.

F2520.1.M44G73 301.45198081 76-54659

ISBN: 0-226-30746-8 (paper)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

Mehinaku:

The Drama of Daily Life in a Brazilian Indian Village

Thomas Gregor

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

For Arthur

Contents

Mehinaku is a dramaturgical description of social relationships among the Mehinaku Indians of the Upper Xingu River in Central Brazil. The theoretical perspective of the book derives, however loosely, from the work of Erving Goffman. His contributions will be frequently cited. Of equal importance, however, has been Robert F. Murphy, who guided my graduate education in anthropology at Columbia University. His original approach to ethnology has always informed my own work.

My field work in Brazil was made possible by many individuals and institutions. Major financial backing came from the National Science Foundation, who generously funded most of my research. Additional support was provided by the National Institute of Mental Health of the U.S. Public Health Service, the Latin American Studies Program and the Center for International Studies at Cornell University, and Vanderbilt University s Re search Council. Within Brazil my work was sponsored by the Museu Nacional in Rio de Janeiro, the Museu Paraense (Emilio Goeldi) in Belm, and the Brazilian Indian Foundation (Fundao Nacional do Indio).

Roberto Cardoso de Oliveira and Rocque de Barrios Laraia of the Universidade de Braslia, Roberto da Matta of the Museu Nacional, and George Zarur, Mario Pompeu and Ney Lande of the Brazilian Indian Foun dation greatly assisted me in finding my way through the bureaucratic tangle that seems to separate all anthropologists from their work; they also helped prepare me for life in an Indian tribe. Paulo Rlo and Miller Hudson of the American Embassy were especially helpful in obtaining the documents needed for my research and in assisting me in many other ways.

Upon my arrival in the Upper Xingu at Posto Leonardo Villas Boas of the Brazilian Indian Agency, I was privileged to meet the administrators of the Post, Claudio and Orlando Villas Boas. These courageous brothers virtually single-handedly established the Xingu National Park (Parque Nacional do Xingu) and protected its frontiers from diamond miners, otter hunters, land speculators and other threats to the Indians land. Throughout my stay in the area, Claudio and Orlando Villas Boas generously gave me the hospitality of the Indian Post, the help of their staff, and their encouragement for my work.

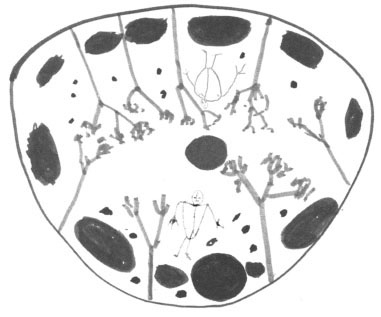

I am also indebted to Bernd Lambert and David J. Thomas for their critical suggestions, and to Jane Hinshaw, Christine Tichy, and Katrina Vanderlip for the artwork.

Finally, I mention the assistance of my family. My father, Arthur S. Gregor, is the ace of editors and critics to whom this book is dedicated. My wife Elinor accompanied me on the first trip to the Mehinaku, is gifted in languages, and has a natural talent for field work. She maintained my good disposition as well as her own through occasionally trying conditions and times when the whole project seemed hopelessly mired. This book is therefore in large measure a joint endeavor.

Introduction

My intention in this book is to describe the way of life of the Mehinaku, a little-known tribe of Indians living in the Mato Grosso of Brazil, by viewing them as performers of social roles.

The first chapter in this introduction examines the validity of the view of life as theater and considers the usefulness and dangers of the dramaturgical metaphor. The second chapter rings up the curtain on the Mehinaku and describes my research among them.

shaped by a spatial setting that compels each individual to become a master of stagecraft and the arts of information control.

In , The Staging of Social Relationships, the focus is on the actors and their participation in social engagements. To take part in everyday relationships, the villagers must be adept at make-up, decorating themselves with the body paints and the ornaments that comprise almost all of their wardrobe. Once adorned and ready to engage their fellows, they will follow guidelines that make for orderly interaction, such as the rules for greetings and farewells that circumscribe each social encounter. In the course of interaction all villagers will attempt to project an image of themselves that identifies them as good citizens: cooperative, generous, and sociable. Finally, the continuing drama of Mehinaku social life will be shaped not only by such encounters but also by patterns for avoiding interaction. Villagers who are ambivalent about social situations need defined ways of disengaging themselves from their fellows. The last chapters of part 3 describe the institutions that separate the Mehinaku and allow them to remain aloof from social encounters.

, The Script for Social Life, examines the roles that the actors perform. Kinsmen and in-laws, tribesmen and foreigners and shamans and clients are the major parts depicted in this final section. As we relate the formal demands of these roles to the theatrical problems involved in staging them, we will also discover that the Mehinaku are not mere puppets manipulated by the demands of their culture but are at times the conscious authors of their own lines.

In each of the major sections of the book, I have attempted to present Mehinaku culture from a definite theoretical point of view, the analysis of the setting, staging, and script of Mehinaku social life. Without losing sight of this purpose, I occasionally take leave of the dramaturgical metaphor to provide necessary background material and a reasonably full description of a little-known people.

Throughout this work I offer translations of Mehinaku words, phrases, and extended passages of speech. Unless otherwise indicated, the translations are free ones, designed to convey the sense of the material rather than its literal meaning. In all direct quotations of speech I have worked from tape recordings or notes taken at or near the time that the passage was spoken. The names of the Mehinaku to whom I attribute these quotesor who are otherwise mentioned in the bookare usually pseudonyms.

Mehinaku words used in this report are written in a simplified phonetic script adapted for the economics of publication. Consonants have values that approximate English, though the j is always soft, as in the dg in judge.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.