Contesting Crime Science

Contesting Crime Science

Our Misplaced Faith in Crime Prevention Technology

Ronald Kramer

and James C. Oleson

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS

University of California Press

Oakland, California

2022 by Ronald Kramer and James C. Oleson

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kramer, Ronald (Senior lecturer), author. | Oleson, James C., 1968 author.

Title: Contesting crime science : our misplaced faith in crime prevention technology / Ronald Kramer and James C. Oleson.

Description: Oakland, California : University of California Press, [2022] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021033099 (print) | LCCN 2021033100 (ebook) | ISBN 9780520299580 (cloth) | ISBN 9780520299597 (paperback) | ISBN 9780520971264 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Crime preventionSocial aspects. | BISAC: SOCIAL SCIENCE / Criminology | SOCIAL SCIENCE / Technology Studies

Classification: LCC HV7431 .K73 2022 (print) | LCC HV7431 (ebook) | DDC 364.4dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021033099

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021033100

Manufactured in the United States of America

30 29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Illustrations

Acknowledgments

This book would not have been possible without the support of many people. We are especially grateful to the wonderful people at University of California Press. Throughout this journey, Maura Roessner has been an incredibly supportive editor, maintaining faith in the project from its initial conception through to its final version. Unlike the faith in crime science, we hope Mauras has not been misplaced. Madison Wetzell, Teresa Iafolla, and Jessica Moll have also been instrumental in ensuring the books production. We loved the cover design at first glance. We are appreciative of the support and help of the many other people who have worked behind the scenes to ensure the manuscript would appear in its best possible form. We are also indebted to Frea Anderson, who worked as a research assistant during the books initial stages. We would like to thank Professor Mike Davis for generously allowing us to reproduce his iconic diagram of dystopian Los Angeles, and would like to thank Jonathan Simon for his generous description of the project. Finally, we greatly appreciate the three reviewers who read earlier drafts of the manuscript and provided much constructive criticism. The book is unquestionably stronger for their contributions.

Ronald Kramer would like to thank his family, Doris, Lee, Sharon, and Glen. Mom, I do not know where I would be without all our trips to Bunnings Warehouse. Special thanks is also owed to Neera R. Jain, especially for her tenacity in keeping up with all the latest Instagram accounts dedicated to rescuing cats, bats, and wombats. I would like to thank my coauthor, James Oleson, for his patience and perseverance. We have not spoken about this yet, but as coauthor I am assuming he is willing to take responsibility for all the errors, misreadings, and unsound arguments throughout the text, even though they arein all likelihoodmy doing. Portions of this book were written while on sabbatical afforded by the University of Auckland.

James Oleson would like to thank (and blame) Ronald Kramer for asking such interesting, heterodox questions and for suggesting this book project. Researching and writing it forced me to think carefully about my assumptions and revealed new vistas within criminology. I would also like to thank the University of Auckland, which provided essential research funding for the project. My contributions to the project would not have been possible without the support of Clare Wilde, Jameson Oleson, and John, Patricia, and Jennifer Oleson.

Introduction

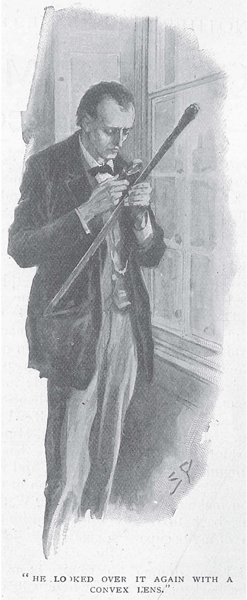

The figure of the master detective can be traced back at least as far as the late nineteenth century. Arthur Conan Doyles character Sherlock Holmes could deduce the whole of an otherwise unsolvable crime by focusing his keen intellect upon a single trifle (there is nothing so important as trifles). Thus, from a flake of ash and the uneven wear on the heel of a boot, Holmes could conjure the criminal in vivid detail: And the murderer? Is a tall man, left-handed, limps with the right leg, wears thick soled shooting boots and a grey cloak, smokes Indian cigars, uses a cigar holder, and carries a blunt penknife in his pocket. There are several other indications, but these may be enough to aid us in our search.

Like magic. Sherlock Holmes introduced the use of tobacco ashes, fingerprints, serology, and printed type just as they were being accepted as legitimate techniques of forensic investigation. It is a matter of some debate whether Sherlock Holmes was more product or source of early crime science.of blood, or a micro-expressionfrom which the whole of the case is revealed. It is such a seductive narrative that the exaggerated power of forensic science has become enshrined in the public imagination. Fingerprints, DNA, lie detectors, offender profiling, and magnetic resonance imaging scans are all new forms of magic, unabashedly invested with the power to resolve even impossible-to-solve crimes. But like other forms of magic, crime science depends upon a suspension of disbelief.

FIGURE 1. Sherlock Holmes examining a cane. Source: The Hound of the Baskervilles, The Strand 22, no. 128 (1901): 124.

CRIME SCIENCE

We understand crime science to be a broad, encompassing, discursive formation. That is, we understand it as a framework constructed from statements, categories, and relationships between concepts, all of which produce criminalized behavior and render it comprehensible in particular ways. This discursive formation of crime science is not monolithic. Rather, it is rhizomatic, functioning as a conceptual grid that underpins a variety of seemingly unrelated offshoots: biological evidence, actuarial assessment, security technologies, and so on. Thus, crime science operates like an archipelago, in which a single formation connects a mountain range, creating what from above the water line appears to be a chain of separate islands. Most scholars focus on the individual islands (manifestations) of crime science, and there are excellent reasons for engaging in such heterogeneous critiques. But it is also crucial to examine the unifying characteristics that interconnect these islands and to identify the central ideological tenets of crime science.

The contours of crime science remain inexact, which is unsurprising since the term lacks a standard definition. Nevertheless, it is possible to eke out a general meaning. Ronald Clarke distinguishes crime science (which is narrowly focused on crime reduction) from mainstream criminology (which is interested in understanding and explaining crime). In his view, criminology strives to understand the why of crime (the criminal), while crime science focuses on the how of crime (the enacting of crime). Whereas criminology attempts to prevent delinquency and reform offenders, crime science seeks to inhibit crime. Criminology concerns itself with long-term social reform, but crime science is interested in immediate crime reduction. Criminology views crime as pathological and opportunity as a secondary consideration (against preeminent distant causes); crime science views crime as normal and opportunity as the central cause. Clarke suggests that the constituent fields of criminology are sociology, psychiatry, law, biology, and genetics; the constituent fields of crime science are environmental criminology, geography, ecology, behavioral psychology, economics, architecture, town planning, computer science, engineering, and design. Criminology draws upon the talents of stakeholders in the criminal justice system, social policy makers, social workers, university teachers, and intellectuals. On the other hand, crime science builds upon the talents of police and the security industry, crime policy makers, architects, town planners, city managers, crime and intelligence analysts, and design, business, and industry.