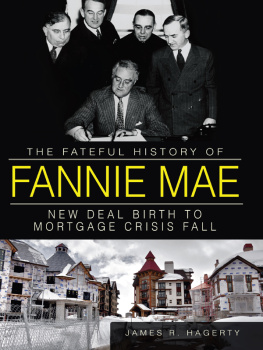

How did the U.S. economy get swept up in the madness of an unsustainable home-lending binge? How can we make sure such foolishness doesnt happen again? The best place to turn for answers is The Fateful History of Fannie Mae, a lucid and meticulously reported book by one of the Wall Street Journals ace reporters, James R. Hagerty. His book epitomizes history with a purpose: showing how seventy years of good intentions, inertia and greed combined to create a financial catastrophe like no other.

George Anders, contributing writer at Forbes magazine and author of

The Rare Find

This is an important book that settles once and for all what Fannie Maes role was in the mortgage crisis. The problem was recognized as early as the Eisenhower administration, yet no oneneither Democrat nor Republicanmanaged to head it off. We should study this book, learn from our mistakes and kill the next budding disaster while there is still time.

Paul Carroll, coauthor of Billion Dollar Lessons

Hagerty makes a valuable contribution to the lessons learned from the financial crisis with his untangling of the complex history of Fannie Mae. His treatment is clear, interesting and fair-minded without being wishy-washy.

Urban C. Lehner, former editor of the Wall Street Journal Asia

In a book that is rigorous, complete and well told, Hagerty explains how Fannie Mae evolved from its inconsequential birth during the Great Depression to a massive financial institution whose demise nearly took down the entire global economy.

Mark Zandi, chief economist, Moodys Analytics

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2012 by James R. Hagerty

All rights reserved

Front cover, top: courtesy of the Library of Congress; bottom: Tamarack Village, courtesy of Alan D. Coogan.

First published 2012

e-book edition 2012

Manufactured in the United States

ISBN 978.1.61423.699.3

print ISBN 978.1.60949.769.9

Library of Congress CIP data applied for.

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Contents

Acknowledgements and Thanks

This book is based on historical documents and interviews with nearly fifty former executives, directors and managers of Fannie Mae, as well as dozens of regulators, government officials, legislators, congressional staffers and bankers.

Thomas H. Stanton kindly gave advice and help with research. Kathryn McMiller, a true friend, dove deeply into files at the Nixon Presidential Library. Lisa Xing and Steve Velaski generously shared their photography. Drew Friedman and David Simonds let me reproduce their cartoons. Along with my own reporting for the Wall Street Journal, I drew on the work of other reporters for that newspaper and Dow Jones Newswires, including Kenneth Bacon, Patrick Barta, Jackie Calmes, John Connor, Dawn Kopecki, Joann Lublin, John McKinnon, Damian Paletta, Jacob Schlesinger, Deborah Solomon, Ruth Simon, Nick Timiraos and John Wilke. With love to my wife, Lorraine; children, Carmen and James; sister Gail; and parents, Marilyn and Jack Hagerty, who taught me my trade.

This book is dedicated to the memory of Carol Hagerty Werner.

Chapter 1

His Name Was Mudd

On the morning of Friday, September 5, 2008, Daniel Mudd, chief executive officer of Fannie Mae, arrived at the companys Georgian red brick headquarters on Wisconsin Avenue in Washington, D.C. A colleague told Mudd he had been summoned to attend a meeting at 3:00 p.m. The host would be James B. Lockhart III, director of the agency responsible for regulating Fannie. Lockhart was a powerful, though little-known, figure in Washington, with long experience as a regulator and entrepreneur. Since high school, he had been a friend of President George W. Bush, who still sometimes called him by a teenage nickname, Juice. The other people due to attend the meeting were more imposing: Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson and Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke.

Normally, Mudd was at ease with the rich and powerful. A son of the former CBS television news anchorman Roger Mudd, he grew up in Washington and was decorated for action in Lebanon as a first lieutenant in the U.S. Marines. He later worked for General Electric in Europe and Asia under the glorious reign of CEO Jack Welch.

Mudd was proud of the work he had done since taking over as CEO of Fannie in late 2004, when an accounting scandal forced out his predecessor. He believed he had changed the companys culture to make it less arrogant and bureaucratic. Fannie had spent hundreds of millions of dollars on a restatement of its accounts to satisfy regulators. We have a solid, successful franchise that earns billions of dollars a year by helping lenders put millions of working families into houses and apartments, the company had stated in a planning document for 2007 through 2011.

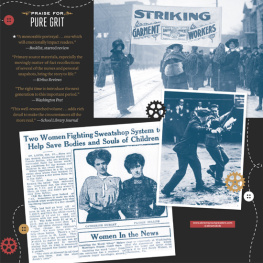

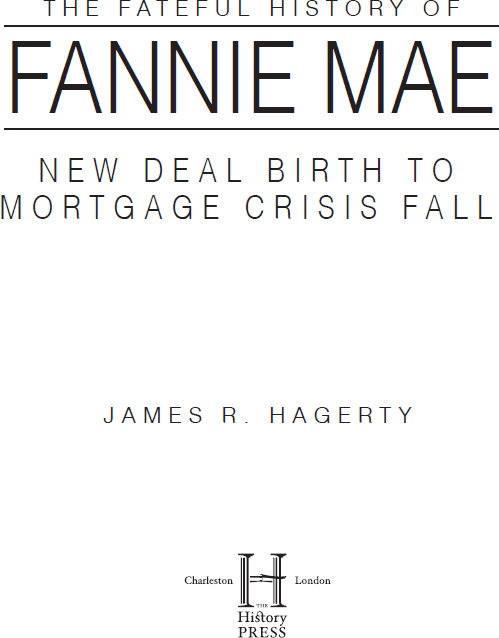

A caricature drawn for the Wall Street Journal in 2006 shows Daniel Mudd under fire from critics. Drawing by Drew Friedman.

But 2007 didnt turn out to be a very good year, as the U.S. housing bust deepened, and 2008 was looking far worse. As an investor in home mortgages, many of them defaulting, Fannie was losing money at the rate of nearly $1 billion a month. The owners of its bondsincluding central banks around the worldwere getting edgy. They had the power to pull the plug on Fannie and, by extension, the U.S. housing industry.

Mudd called the Treasury and asked to speak to Secretary Paulson, a one-time college football offensive lineman and the former CEO of the Wall Street investment bank Goldman Sachs. Mudd thought he had a good working relationship with the Treasury secretary and wanted to be part of the solutiona solution that would reassure investors that Fannie had solid government backing and could survive in its current form, under its current management.

When Paulson picked up the phone, he offered Mudd no comfort. Paulson declined to explain why the meeting was being called. Dan, Paulson later recalled saying, if I could tell you, I wouldnt be calling the meeting.

Mudd called H. Rodgin Rodge Cohen, chairman of the law firm Sullivan & Cromwell. Fannies chairman, Stephen Ashley, who was at his summer house in Vermont, got a call at around 9:00 a.m. from the company. A jet was being sent to bring him back to Washington. My wife said, Whats that all about? Ashley recalled later. I said, It isnt good.

Mudd, Ashley and the companys general counsel, Beth Wilkinson, rode in a Fannie car to the Washington office of Sullivan & Cromwell to huddle with Cohen early that afternoon. Then the four of them walked a few blocks to the regulators office at the corner of G and 17th Streets.

Next page