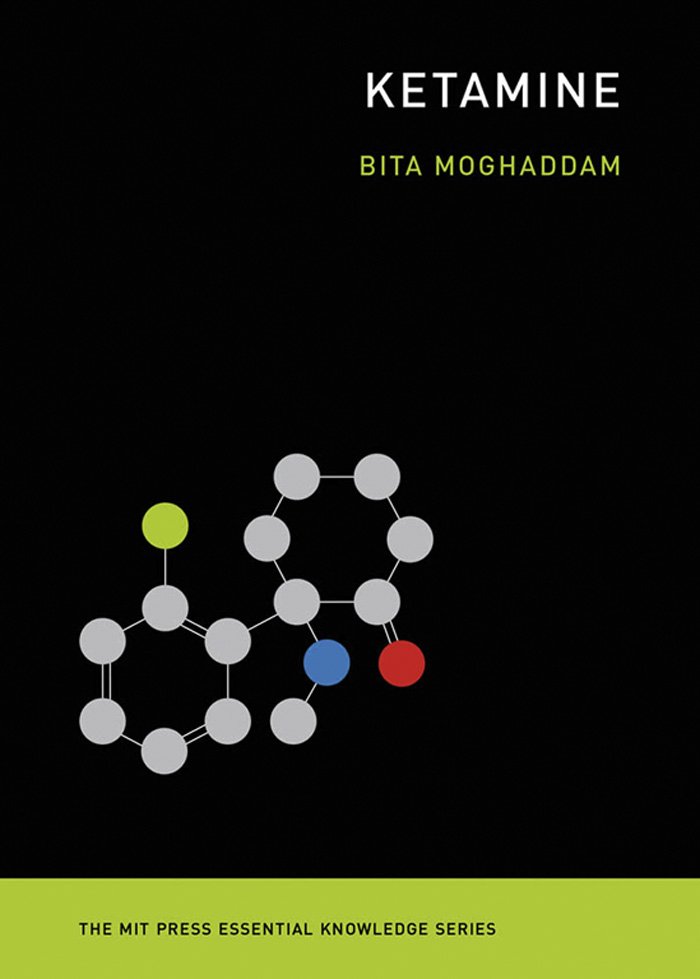

Ketamine

The MIT Press Essential Knowledge Series

A complete list of the titles in this series appears at the back of this book.

Ketamine

Bita Moghaddam

The MIT Press|Cambridge, Massachusetts|London, England

2021 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

This book was set in Chaparral Pro by New Best-set Typesetters Ltd.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Moghaddam, Bita, author.

Title: Ketamine / Bita Moghaddam.

Other titles: MIT Press essential knowledge series.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The MIT Press, [2021] | Series: MIT press essential knowledge series | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020010212 | ISBN 9780262542241 (paperback)

Subjects: MESH: Ketaminetherapeutic use | Ketaminechemistry | Ketaminepharmacology | Antidepressive Agents | Depressive Disorderdrug therapy

Classification: LCC RD86.K4 | NLM QV 81 | DDC 615.7/81dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020010212

10987654321

d_r0

For Maman Shokooh

Contents

Series Foreword

The MIT Press Essential Knowledge series offers accessible, concise, beautifully produced pocket-size books on topics of current interest. Written by leading thinkers, the books in this series deliver expert overviews of subjects that range from the cultural and the historical to the scientific and the technical.

In todays era of instant information gratification, we have ready access to opinions, rationalizations, and superficial descriptions. Much harder to come by is the foundational knowledge that informs a principled understanding of the world. Essential Knowledge books fill that need. Synthesizing specialized subject matter for nonspecialists and engaging critical topics through fundamentals, each of these compact volumes offers readers a point of access to complex ideas.

Preface

On March 4, 2019, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved ketamine for treatment of depression. This approval was touted by major news outlets as the biggest advance for depression in years. The director of the National Institute of Mental Health, Joshua Gordon, enthusiastically tweeted about the approval, calling it amazing news and the first truly novel drug in decades for treatment of a major psychiatric illness. This was a remarkable ascent for a fifty-seven-year-old compound, a Vietnam-era combat anesthetic, and a 1980s club drug. The rush to approval was also unusual given the lack of strength of the scientific evidence, with only four small studies showing little efficacy versus placebo for treating depression.

Ketamine was touted as the biggest advance for depression in years.

Excitement has been followed by caution as concerns about unknown side effects of ketamine have been mounting. The FDA assigned a black box warning to ketamine, which is the most serious safety warning assigned to a drug by the agency. There are virtually no studies that have examined long-term effects of ketamine on the human brain. This is compounded by some reports of tolerance being developed to ketamine, which would necessitate administering higher doses of the drug to relieve depression. Laboratory studies show that high doses may be toxic to brain cells, especially to a younger brain. Despite all the unknowns, clinical scientists are continuing efforts to get approval for the use of ketamine for suicide prevention in adolescents, as well as treatment of other illnesses such as PTSD.

This apparent haste reflects the stagnant state of biomedical research and the pharmaceutical industry in developing and marketing novel treatments for symptoms of brain illnesses such as depression and PTSD. The incidence of these conditions has been skyrocketing, whereas our drug treatment approaches have not improved for decades. Ketamine works differently than old antidepressant drugs like Prozac, which remain the standard way of treating depression. It acts on different brain proteins and has a rapid onset of effect. Ketamine therefore has the potential to revolutionize our understanding of the neuroscience of depression and how we could treat it more effectively. Even if emerging side effects dampen the current push to make ketamine available to patients, there remains excitement about this molecule as a scientific tool that can advance our understanding of depression.

This book aims to synthesize the scientific history and the biology of ketamine for a general audience. It will begin by providing an account of what led to the chemical synthesis of ketamine and the progression of its clinical and recreational use in the last six decades, leading to the discovery of its antidepressant effects. The status of the field after the discovery of the antidepressant properties of ketamine is further discussed in the context of making ketamine clinically accessible to patients and profitable. The book will then explain our current understanding of how ketamine affects brain function, including neuroscience theories that try to explain its antidepressant properties. It will end with some predictions about future directions in this field, regardless of the sustainability of ketamine as an antidepressant drug.

1

The Molecule Ketamine

Discovery of Ketamine

Ketamine was synthesized in 1962 by Calvin Stevens, a professor of organic chemistry at Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan. This discovery was not fortuitous. At the time, Calvin Stevens was working in collaboration with the Detroit-based drug company Parke-Davis to make derivatives of ketamines parent compound, the hallucinogen phencyclidine (PCP, aka angel dust).

Unlike the deliberate synthesis of ketamine, PCP had been discovered in 1956 by somewhat of a fluke chemical reaction. A chemist at Parke-Davis named Victor Maddox was attempting to make novel compounds that could penetrate the brain and hopefully have therapeutic effects. It is important to appreciate that the 1950s were the heyday of neuropsychopharmcology, a scientific field focused on developing and studying drugs that affect behavior in the service of treating symptoms of psychiatric disorders. In the earlier part of the century, there had been several serendipitous discoveries of drugs that influenced behavioral states, including drugs that caused sedation, improved mood, or had antipsychotic properties.

During World War II, efforts in this area of work had slowed down, but the postwar era saw flourishing pharmaceutical industries in Europe and North America, attracting talented chemists with close ties to academic medicine to synthesize more of these so-called psychoactive drugs. The modus operandi was to synthesize derivatives of existing compounds that could penetrate the brain and affect behavior or perception. These compounds were then quickly tested in animals and moved forward to human use. Nearly all of our current psychiatric drugs, including the most commonly used drugs to treat symptoms such as anxiety, depression, and psychosis, are the same as or me-too versions of drugs synthesized in that era.

An interesting example, relevant to the modern-day discovery of the antidepressant effects of ketamine, was the serendipitous discovery of our current antidepressant drugs. The drugs isoniazid and iproniazid were developed soon after the war for treatment of tuberculosis (TB) from leftover German rocket fuel (nitrazine). Doctors treating patients with TB noted euphoria and improvement of mood in some of them. This observation promoted these doctors to consider the potential usefulness of these drugs as

Next page