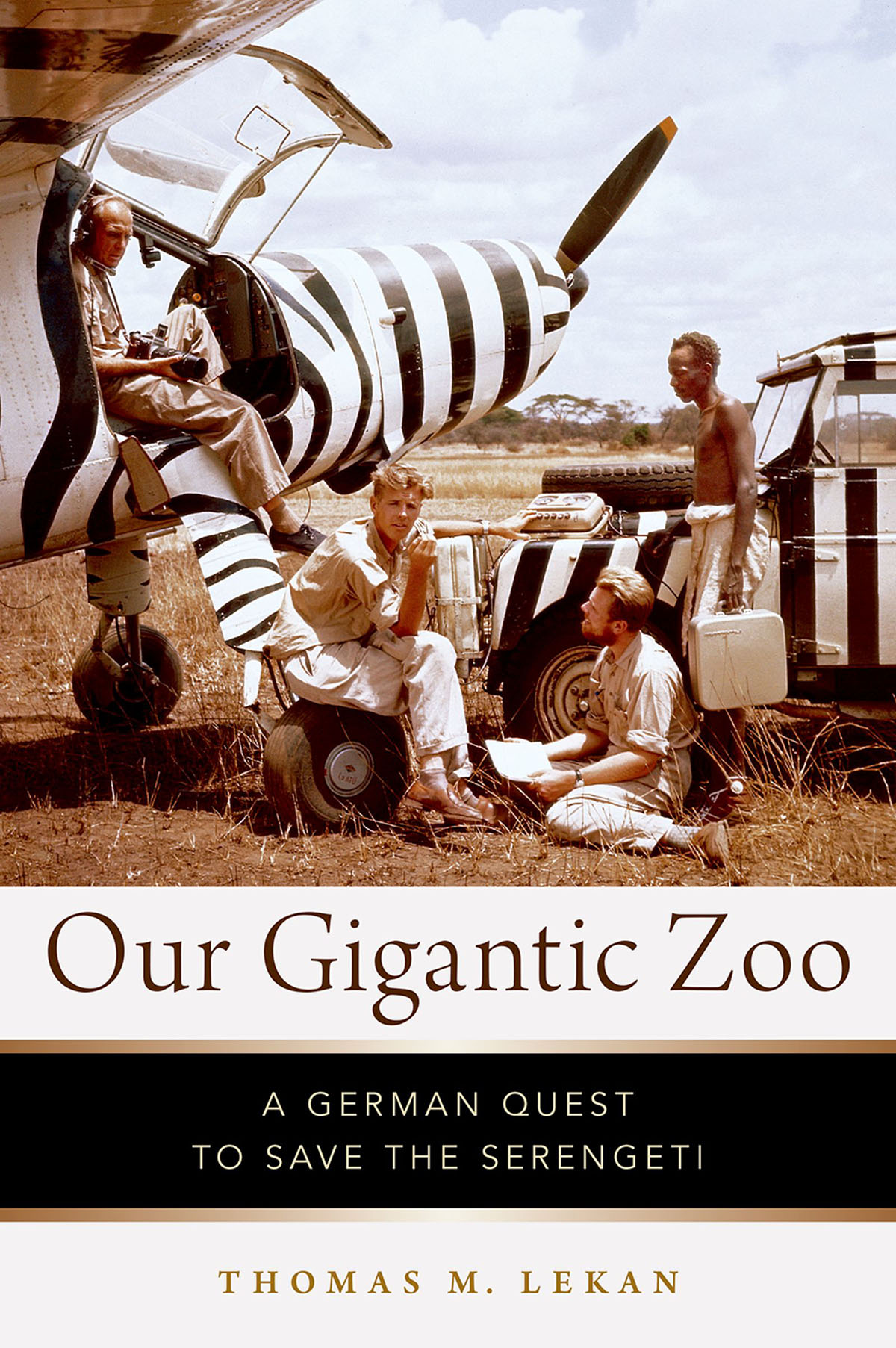

Our Gigantic Zoo

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress

ISBN 9780199843671

eISBN 9780190935368

Contents

This book brings together reflections on nature conservation and the entangled fates of humans and our non-human companions that have been simmering for decades. Our Gigantic Zoo: A German Quest to Save the Serengeti focuses on the environmental-historical significance of the former Frankfurt Zoological Society director Bernhard Grzimek, who was arguably Europes most important wildlife conservationist of the twentieth century. Germans from both sides of the wall remember him primarily for his Sunday night television program A Place for Animals, the longest running show in German history (19561987), and the documentary Serengeti Shall Not Die (1959) produced with his son Michael. The film prompted Western audiences to send donations to protect the Serengeti and other national parks in Africa, but this book shows that the real sacrifice came from East Africans, particularly the pastoralist groups who had to leave their homelands to make room for tourists or the urbanites who paid the taxes that subsidized the park systems roads, lodges, and staff salaries. Grzimeks troubles with wilderness were not the same as those of more celebrated preservationists such as John Muir or Julian Huxley. As a veterinarian and former agricultural minister, Grzimek understood better than most the connections between ecological protection at home and abroad; he fought just as hard to save chickens from industrialized slaughter in Europe as he did to preserve endangered black rhinos in the Ngorongoro Crater in Tanzania.

Our Gigantic Zoo is a product of deep ambivalence about my own fascination with celebrity conservationists and media images of creatures great and small during roughly the same years that Grzimek was at the height of his influence. Viewing long-forgotten episodes of A Place for Animals, Im reminded of my favorite television program of the 1970s: Mutual of Omahas Wild Kingdom, hosted by Marlin Perkins of the St. Louis Zoo. My parents thought the show would satisfy my scientific curiosity, and the safe and harmonious animal scenes appeared resolutely apolitical during a time when they worried about the violent images of the war in Vietnam appearing on the nightly news. Perkins always left his sidekick Jim Fowler to do all the dangerous work with animals, and Jims antics served as the perfect segue to selling life insurance (Jim may not escape the jaws of the Upper Nile crocodile, but you can protect YOUR family by contacting Mutual of Omaha about a life insurance policy... ).

I did not know Grzimek the celebrity as a child; few North Americans did, though many German historians credit him with transforming the straitlaced boys and girls of the Adenauer years into the firebrand Green activists of the 1970s. Indeed, as he developed the show over the late 1960s and 1970s, Grzimek became much more activist, calling on his fellow West Germans to risk more democracy in ways that Perkinss corporate-sponsored Wild Kingdom would never dare. Yet I recognize now that A Place for Animals and Serengeti Shall Not Die confined scenes of danger and death to the natural give-and-take between predator and prey in the African savannas. The human-on-human violence triggered by the legacies of European colonialism, anti-imperialist struggles, Cold War proxy wars, and the land alienations needed to create national parks in sub-Saharan Africa and elsewhere never made it to the screen. That violence came from the realm of politics, and I accepted that the ecological crisis facing humanity was above these fleeting concerns. All I knew as a teenager was that beloved charismatic mammals were endangered, and that was enough for me to send small donations to the World Wildlife Fund, to study marine ecology and anthropology in Australia, and to work in environmental policy in Washington, DC, in the early 1990s. For various reasons, I became disillusioned with the quantitative quagmire of policy work and turned toward humanities perspectives. Projects about managing hazardous wastes or mitigating wetland destruction largely involved trying to determine an acceptable number of cancer deaths or putting a price tag on aesthetic experiences for cost-benefit analysesa prelude to the ecosystem services approach that now dominates conservation in the neoliberal era. As I show in the pages that follow, this approach had its origins in the early 1960s as former imperial conservationists tried to sell African leaders on the benefits of wildlife for their newly independent countries.

As I began to fashion a second monograph, I imagined it initially as a kind of sequel to my first one on landscape preservation and national and regional identities in Germany. I had not dealt sufficiently with the issue of tourism in the first book, especially given Germans well-known penchant for seeking out nature and wilderness abroad (a real glimpse of this came on a trip to Bryce Canyon National Park in June 2007, where the gift shops checkout counter had another sign affixed to it: Kasse). Inspired by Samuel Hayss insights about the relationship between white-collar consumerism and the post-material values that spurred modern environmentalism, I wanted to know how the dialectic between consumption and conservation in so-called soft or green tourism informed twentieth-century German environmentalism. And so, with Hasso Spodes help, I began to look into the huge array of tourist guidebooks and tourist ephemera about German landscapes found at the Historical Archive of Tourism in Berlin and put together a first draft of a monograph during a generous leave made possible by an American Council of Learned Societies fellowship in 20062007.

While reading hiking guides to the Black Forest, I was drawn to the shelves of German-language guidebooks about foreign destinations and how these guidebooks framed places such as Africa, South America, and Asia for German-speaking visitorsa project for another time, I thought. I knew that Grzimek was a critical figure in postwar German environmentalism and tourism promotion, famous for encouraging tourists to save Africas precious wildlife by booking package tours to the Serengeti, but I imagined that he would take up a chapter of the booknothing more. In 20082009, I had done talks on Grzimek and his role in developing East African tourism at the American Society for Environmental History in Tallahassee, Florida, the Chasing Eden workshop at the University of Exeter, the Harvard German Studies Seminar, and as the Dante Lecturer at Manhattan College. The feedback at those venues was encouraging: many thanks to Timothy Cooper and Gregg Mitman for their comments on media and environmental activism and to Chris Conte, Gregory Maddox, Roderick Neumann, Jamie Monson, and Thaddeus Sunseri for underscoring Grzimeks importance to environmental historians of Tanzania. Thaddeus remained unbelievably generous with his advice thereafter, critiquing and serving as referee for grant applications and reading chapters of the draft manuscript. His deep knowledge of East African social history, forest reserves, disease impacts, and cattle cultures have informed this book; any mistakes in connecting the dots remain my own.