Imagining Serengeti

NEW AFRICAN HISTORIES SERIES

Series editors: Jean Allman and Allen Isaacman

David William Cohen and E. S. Atieno Odhiambo, The Risks of Knowledge: Investigations into the Death of the Hon. Minister John Robert Ouko in Kenya, 1990

Belinda Bozzoli, Theatres of Struggle and the End of Apartheid

Gary Kynoch, We Are Fighting the World: A History of Marashea Gangs in South Africa, 19471999

Stephanie Newell, The Forgers Tale: The Search for Odeziaku

Jacob A. Tropp, Natures of Colonial Change: Environmental Relations in the Making of the Transkei

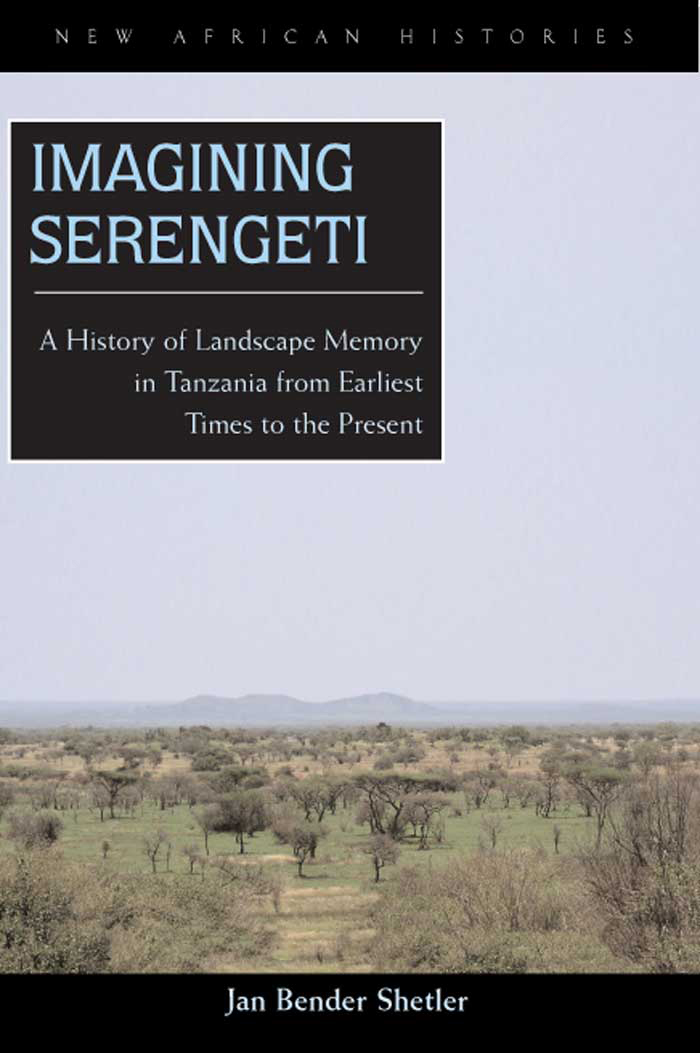

Jan Bender Shetler, Imagining Serengeti: A History of Landscape Memory in Tanzania from Earliest Times to the Present

Imagining Serengeti

A History of Landscape Memory in Tanzania from Earliest Times to the Present

Jan Bender Shetler

OHIO UNIVERSITY PRESS

ATHENS

Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio 45701

2007 by Ohio University Press

www.ohio.edu/oupress/

Printed in the United States of America

All rights reserved

Ohio University Press books are printed on acid-free paper

15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Shetler, Jan Bender.

Imagining Serengeti : a history of landscape memory in Tanzania from earliest times to the present / Jan Bender Shetler.

p. cm.(New African histories series)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8214-1749-2 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-8214-1749-5 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-8214-1750-8 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-8214-1750-9 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Landscape assessmentTanzaniaSerengeti National Park. 2. Landscape changesTanzaniaSerengeti National Park. 3. LandscapeSocial aspectsTanzaniaSerengeti National Park. 4. Geographical perceptionTanzaniaSerengeti National Park. 5. Oral traditionTanzaniaSerengeti National Park. I. Title.

GF91.T36S54 2007

967.8--dc22

2006101502

Contents

Illustrations

MAPS

FIGURES

TABLES

Preface

This Book Is Divided into two main parts, roughly representing historical memory before and after the nineteenth century. The mid-nineteenth century is the critical chronological breaking point between these parts of the book because after that time oral traditions become more historically grounded and written sources also become available. The first section establishes the oldest and most basic ways of seeing the landscapeways inherited from the distant past but still relevant todayand presents them in relation to the three different genres of oral tradition on which they are based. The chapters in this section explore the core spatial images in each of these genres and the appearance of these same images in other kinds of sources. These different, though intersecting, views of the landscape have ordered western Serengeti interactions with the environment, beginning with the oldest kind of oral traditions that go back to the first Bantu speakers who settled in the region about 300 CE and continuing into the most recent conversations about the park. They represent a set of strategies or approaches that western Serengeti peoples adapted in a myriad of ways to transform their society in response to changing historical circumstances.

The second section, or final three chapters of the book, then looks at how western Serengeti peoples used these three precolonial views of the landscape embedded in oral traditions in more recent social transformations. Each chapter analyzes the challenges and conflicts chronicled in historical traditions that emerged as western Serengeti peoples adapted to three major crises: the late nineteenth-century disasters, colonial rule, and the creation of Serengeti National Park. In the second section, we see how elders responded to new historical circumstances in creative ways and ultimately succeeded in adapting to change by recontextualizing older ways of seeing and using the landscape. The second section also describes new ways of seeing the landscape brought by new encounters. Although the book proceeds chronologically, in the order in which these different ways of seeing the landscape emerged, there is a constant reference back and forth in time, since spatial images cannot easily be locked into set time frames. The reader is alerted when evidence is taken from a different time period and when applications are made in the present, thus avoiding the pitfall of assuming a timeless tradition in the ethnographic present. The book ends with western Serengeti peoples conversations about how to solve the problems they face in relation to the park that are based on a global conservationist view of the landscape.

Acknowledgments

This Book Has Been ten years in the making and along the way has incurred many debts of gratitude that can never be fully repaid. I am grateful for the institutional support I received during the course of my graduate studies and research in Tanzania. The dissertation research was assisted by a grant from the Joint Committee on African Studies of the Social Science Research Council and the American Council of Learned Societies with funds provided by the Ford, Mellon, and Rockefeller Foundations. I also received a research grant from the Institute of International Education under the U.S. Fulbright Student Program (199596). In 2003 a generous research grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities allowed me to take a semester for additional research in Tanzania and writing. I express my sincere gratitude to the government of Tanzania for permission to do research in the country under the auspices of the Tanzania Commission for Science and Technology and the history department of the University of Dar es Salaam. Members of that department were always generous with their time and support. Special thanks to Dr. Fred J. Kaijage, Dr. Bertram Mapunda, Dr. Rugatiri D. K. Mekacha, Dr. B. Itandala, Dr. I. N. Kimambo, Dr. Nestor Luanda, and Dr. Yusufu Q. Lawi. I am thankful to the patient staff at the Tanzania National Archives, the East Africana Collection at the University of Dar es Salaam library, the Bodleian Library at Rhodes House (UK), the Public Records Office (UK), the University of Florida Africana collection, and the Goshen (Indiana) College library. Gratitude is also extended to Markus Borner of Frankfurt Zoological Society and the Serengeti Research Institute for use of their facilities while my husband Peter was working with their GIS project and for sharing mapping data.

The University of Florida, where I studied, and Goshen College, where I teach, have been excellent homes for intellectual growth. I thank the history department and the African Studies Center at the University of Florida for their support, received over my years there in the form of assistantships, travel grants, writing fellowships, and much more. At the University of Florida I experienced an atmosphere of creative interdisciplinary interaction with a community of scholars who demonstrated an unusually cooperative spirit, including Holly Hanson, Tracy Baton, Marcia Good, Edda Fields, Catherine Bogosian, Jim Ellison, Todd Leedy, Kearsley Stewart, and Kym Morrison. My deepest appreciation is extended to my mentors, especially Steve Feierman, Hunt Davis, and David Schoenbrun, who have given so much of their time and intellectual inspiration to my work. Goshen College provided ongoing financial and physical support for research through the Minninger Center and the Multicultural Affairs Office. A wonderful group of colleagues and students on Wyse third at Goshen College provided inspiration and grounding in the last phase of the research and writing. Thanks especially John D. Roth, Steve Nolt, and Lee Roy Berry in the History Department. Perhaps unknowingly, my students in the Environmental History classes of 2002 and 2004 helped me to think through many of the issues in the book. Thanks also to my wonderful research assistants, Nyangere Faini, Rose Wangombe Mtoka, Jessica Meyers, and Emily Hershberger. Many people read partial or complete drafts of the project and gave me comments along the way: Holly Hanson, Marcia Good, David Schoenbrun, Elizabeth Garland, Elizabeth Smucker, Kathleen Smythe, Richard Waller, and the readers and my editors at Ohio University Press, including Jean Allman and Allan Isaacman, whose suggestions made the book so much better. I am most grateful. While I was in Dar es Salaam in 1996 and 2003 I enjoyed the good conversation and camaraderie of a wider community of scholars staying at the TYCS hostel and working in the archives. Even as I finished writing my dissertation on our farm in Dove Creek, Colorado, the lovely community around me gave me the sustenance necessary to do the job. A constant source of input and ideas were my colleagues at the Tanzania Studies Association.