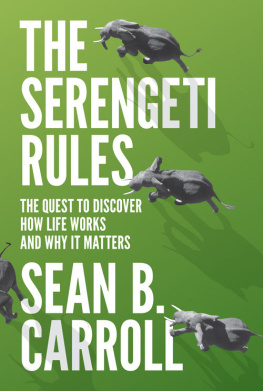

Copyright 2016 by Sean B. Carroll

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work

should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

Cover design by Chris Ferrante

Cover photograph TimFitzharris.com

Fourth printing, first paperback printing, 2017

All Rights Reserved

Cloth ISBN 978-0-691-16742-8

Paper ISBN 978-0-691-17568-3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015038116

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Sabon Next LT Pro and League Gothic

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

5 7 9 10 8 6

For the animals,

and the people looking out for them

and, more or less, of those who are connected with us, do depend upon our knowing something of the rules of a game infinitely more difficult and complicated than chess. It is a game which has been played for untold ages.... The chessboard is the world, the pieces are the phenomena of the universe, the rules of the game are what we call the laws of Nature.

THOMAS H. HUXLEY, A LIBERAL EDUCATION(1868)

CONTENTS

THE SERENGETI RULES

FIGURE 1 The Naabi Entrance Gate, Serengeti National Park.

Photo courtesy of Patrick Carroll.

INTRODUCTION

MIRACLES AND WONDER

The corrugated gravel road known officially as Tanzania Route B144 provides a bone-jarring, teeth-rattling, bladder-testing connection between two of the great wonders of Africa.

At its eastern end stand the massive green slopes of Ngorogoro Crater, a giant, more than ten-mile-wide caldera formed by the collapse of one of the many extinct volcanoes of the Great Rift Valley, and home to more than 25,000 large mammals. To the west lie the vast plains of the Serengeti, our destination on this cloudless, postcard-perfect day.

The route in between is a stark contrast to the lush Ngorogoro highlands. There is no visible source of water; the Maasai herdsmen and boys we pass in their bright red shuka graze their livestock on whatever brown stubble they can find. But as we bounce our way through the first simply marked gate to Serengeti National Park, the landscape changes.

The Maasai vanish, and the nearly barren tracts they use are replaced by straw-colored grasslands, and instead of cattle and goats, sleek black-striped Thomson gazelles look up to see who or what is kicking up dust all over their breakfast.

The anticipation in our Land Cruiser rises. Where there are gazelles, there may be other creatures lurking in the tall grass. We pop open the top of the vehicle, stand up, and with the African rhythms of Paul Simons Graceland playing in my head, I start to scan back and forth. This is my first visit to what the Maasai call Serengit for endless plains. Joining me on my pilgrimage to this legendary wildlife sanctuary is my family:

pilgrims with families and we are going to Graceland...

At first, I am a bit concerned. Where is all the wildlife? Yes, it is the dry season, but things look really dry. Can this place live up to its reputation?

The continuous grass plain is broken only occasionally by small rocky hills, or kopjes. From their granite boulders, animals (or tourists) can scan around for miles. There are also gray or red termite mounds projecting up to a few feet over the tops of the grass. Ones eye is naturally drawn to these shapes.

What is that over there? asks a voice in the vehicle.

A couple of us grab our binoculars and zero in on a lone mound a couple of hundred yards away.

Lion!

A golden lioness is standing on top, staring out over the surrounding grass.

OK, so they are here, I murmur to myself. But this is the famous Serengeti?

It is going to be really hard to spot things in this tall dry grass. I am the only biologist in my clan, I cant expect anyone else to want to do this for days on end.

As we drive on, some streaks of green grass appear, with a few iconic flat-topped acacia trees sprinkled about. A creek bed meanders through the green patches, and it has plenty of water. We go over a small rise, round a bend, and skid to a stopzebra and wildebeest block the road and fill the entire view.

It is a sea of stripes. Perhaps 2,000 or more animals have gathered near a large waterhole, raising a ruckus. The zebras calls are something between a bark and a laugh: kwa-ha, kwa-ha, while the wildebeest seem to just mutter huh? These herds are stragglers from the greatest animal migration on the planet, when as many 1 million wildebeest, 200,000 zebras, and tens of thousands of other animals follow the rains north to greener grazing grounds.

Coming next to the waterhole from over the small rise on our leftthe Dawn Patrola parade of elephants with several youngsters scurrying to keep up. The herds part to make way.

From that point on, the Serengeti offers an unending canvas containing mammals of many sizes, shapes, and colors: small gray warthogs with tails standing straight up like our radio antenna; not two or three but at least nine species of antelopethe tiny dik-dik, the massive eland, impala, topi, waterbuck, hartebeest, Thomsons and the larger Grants gazelles, and the ubiquitous wildebeest; black-backed jackals; towering Masai giraffe; and yes, all three big cats on this first day, including several more lions, a leopard dozing in a tree, and a cheetah posing just feet from the road.

Although I have seen many pictures and movies, nothing prepared me for, nor spoiled the thrill of, encountering this stunning scenery for the first time.

A strange, but very pleasant feeling sweeps over me as I gaze across a wide green valley, with multitudes of creatures and acacia stretching as far as I can see, and the sun beginning to set behind the silhouettes of the surrounding foothills. Although it is the first time I have ever been to Tanzania, I feel at home.

And indeed, this is home. For across the Rift Valley of East Africa lay buried the bones of my and your ancestors, and those of our ancestors ancestors. Sandwiched between Ngorogoro Crater and the Serengeti lies Olduvai Gorge, a thirty-mile-long twisting maze of badlands. It was in its eroding hillsides (just three miles off of the current B144) that, after decades of searching, Mary and Louis Leakey (and their sons) unearthed not one, not two, but three different species of hominids that had lived in East Africa 1.5 to 1.8 million years ago. Thirty miles to the south at Laetoli, Mary and her team later discovered 3.6-million-year-old footprints made by our small-brained but upright-walking ancestor Australopithecus afarensis.

Those hard-earned hominid bones were precious needles in a haystack of other animal fossils that tell us that, although the specific actors have changed, the drama we can still see todayof fleet herds of grazing animals trying to stay out of the reach of a number of wily predatorshas been playing for thousands of millennia. Hoards of ancient stone tools found around Olduvai and butchery marks on those bones also tell us how our ancestors were not merely spectators but very much a part of the action.

Next page