American Covenant

Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Amasa Stone Mather of the Class of 1907, Yale College.

Copyright 2021 by Michael A. Soukup and Gary E. Machlis.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please email (UK office).

Set in Gotham and Adobe Garamond types by IDS Infotech Ltd.

Printed in the United States of America.

ISBN 978-0-300-14035-4 (alk. paper)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020943782

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To our children and grandchildren

Contents

American Covenant

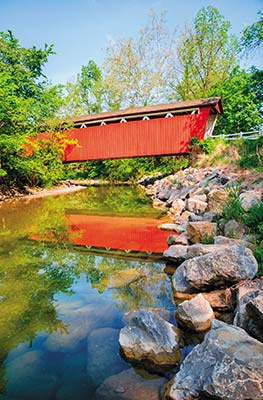

Mount Rainier National Park. Iconic national parks like Mount Rainier inspire Americans. (Photograph by Sage Ross)

Good Fortune

There is a vast, strange, and beautiful place at the southern tip of Florida that every American should see. The Everglades, with its expanse of water fifty miles wide in places, has for thousands of years flowed slowly over porous limestone, sand, and peat from Lake Okeechobee to the Gulf of Mexico. In the poetic phrase of Marjory Stoneman Douglas, this river of grass is quietly majestic, fecund, and richly alive. It is a subtropical paradise or a foreboding wilderness, depending on how you approach it. Experiences in the Everglades are often unforgettable.

The Everglades system receives water from as far north as Orlando via overflows from Lake Okeechobee. Its flat terrain and shallow waters dominate South Florida. Along the way, the glades are made up of sawgrass prairies, tree islands, hardwood hammocks (where slight elevations allow their growth), marl prairies, cypress stands, freshwater sloughs, pinelands, coastal prairies, mangrove swamps, and the marine and brackish areas along Florida Bay. Guidebooks list its marvelous wildlife in our national vernacular: American alligators and American crocodiles; Florida redbelly, soft-shell, and loggerhead turtles; green tree and leopard frogs; apple snails; Florida panthers and bobcats; zebra butterflies; swallowtail kites, Everglades snail kites, limpkins, roseate spoonbills, brown pelicans, and anhingas; great blue, white, and green herons; wood storks, snowy egrets, white ibises, purple gallinules, white-crowned pigeons, barred owls, black vultures, flamingos, and Some twenty-three species of native snakes, including six poisonous ones, add to the Everglades image as a stark, somewhat foreboding, but compelling place. Here wildlife stalks, slithers, and swims among millions of acres of sawgrass, swamp lilies, bull thistles, strap ferns, air plants, gumbo limbo trees, slash pines, royal palms, saw-palmettos, strangler figs, and dwarf cypress. The Everglades authenticity as a desolate and starkly beautiful destination attracts adventurers from all over the world.

The Everglades has been in many ways Americas last eastern frontier. It has held a unique place in Americas human history, replete with pirates, politicians, plume hunters, alligator poachers, and assorted outlaws. Long before that it was home to Native Americans such as the Calusa and the Miami, and it remains to this day the home of the Cow Creek Seminole and the Miccosukee peoples. More recently the Everglades has also stood in the way of South Floridas rapacious appetite for development.

While stubbornly resisting huge public and private projects to drain it entirely, by the early twentieth century the Everglades was being diminished to the extent that there was mounting concern that this one-of-a-kind place needed protection or it would be forever lost. A large portion of the glades just below Lake Okeechobee had already become the Everglades Agricultural Area700,000 acres of sugar cane fields and vegetable farmsas huge public works projects were beginning to control floods and provide for agricultural and municipal water supplies. Massive public works projects enabled constant human encroachment along its periphery, with cities, suburbs, universities, and farms occupying areas that were once Everglades wetlands.

Everglades National Park was something new, a national park established to protect the southern Everglades, its strange wildness, and its curious intersection of temperate and tropical plants and animals. It was to be a national park without majestic mountains; indeed, the park has a maximum elevation of 10 feet over its 1.5 million acres. There is no breathtaking canyon or giant trees. It was the first park established largely to protect the biology of an immense and complicated wetland. The struggle to preserve this precious place is an object lesson for the broader struggles facing the preservation of national parks across America. A key objective in establishing the national park at the downstream end of the Everglades was to preserve the colonies of wading birdsibises, wood storks, and egretswhose massive flights once could block out the sun, as well as a significant portion of the Everglades subtropical assemblage of alligators, crocodiles, snail kites, Florida panthers, and manatees. Today there remain places in the park where you can trek or boat and see a half dozen endangered species in an afternoon.

Yet by the 1960s the wading bird colonies were declining, and by the 1970s and 1980s, most were gone. The most widely cited (though It was becoming clear that providing national park status, in and of itself, had not guaranteed protection of the Everglades from the consequences of intense development outside its boundary. South Floridas demand for flood control, crop irrigation, and water supply was disrupting the processes that created and maintained the Everglades ecosystem.

Ominously, a mere decade after park designation, the managers of Everglades National Park found themselves failing in their mission. Worse, they had no clear understanding of why the decline in nesting wading birds was happening or what should be done to reverse the demise of one of the parks signature resources. The traditions and within-boundary management successes of the great western parks had little relevance to a park that was dependent on a landscape rapidly changing thanks to human hubris and interference.

Although the Everglades story is an extreme example of a park in peril, many other parks today are surrounded by changing landscapes and processes beyond their managers understanding and control. The fundamental lesson from the Everglades is that, if national parks are to persist, national park staffs must, first and foremost, have an in-depth science-based understanding of the resources they manage and an effective means of sharing that understanding with advocates and decision makers at all levels of our society. Herein we seek to champion a solid science foundation for park management as an absolute requirement for the salvation of Americas grand National Park System and its reflection of our extraordinary natural heritage.

We also hope to convey the urgency of the need to begin the process of incorporating science into the daily business of every national park. As this will require major institutional and cultural change in the agency that manages national parks, there is no time to waste. In later chapters we offer our thoughts on what needs to be done to truly protect national parks.

Next page