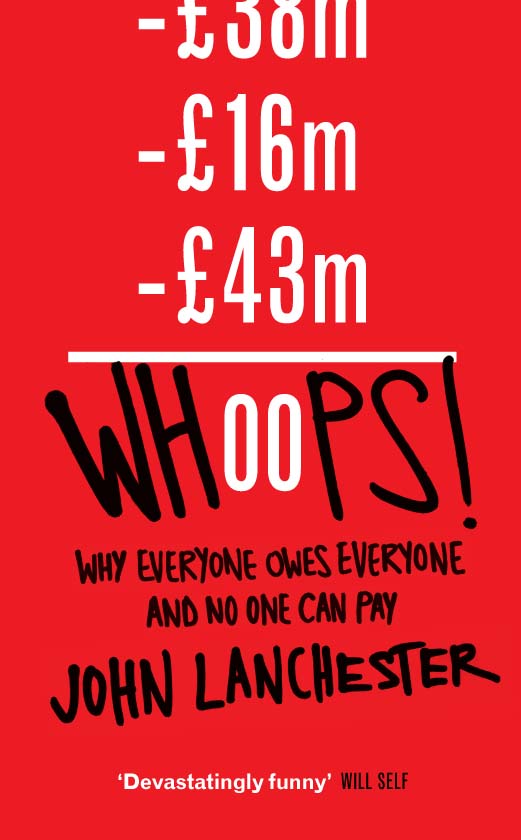

John Lanchester is a novelist, journalist and winner of the Whitbread First Novel Award and the E. M. Forster Award, among other prizes. His books have been translated into more than twenty languages. He is a regular contributor to the London Review of Books and the New Yorker and has a monthly column in Esquire . He has written regularly on finance for the New Yorker and the LRB . In January 2008 his reflective piece on our love affair with the city, Cityphilia, published in the LRB , predicted a worldwide crash based on the misuse of financial derivatives and generated a great deal of debate on its publication.

John Lanchester was born in Hamburg and brought up in South-East Asia; he now lives in London.

Whoops!

Why Everyone Owes Everyone and No One Can Pay

JOHN LANCHESTER

ALLEN LANE

an imprint of

PENGUIN BOOKS

Acknowledgements

Mary-Kay Wilmers was the onlie begetter of this book. It was her idea for me to write about banks in the London Review of Books which got me started, and her subsequent suggestions for follow-up pieces which kept me going. This book wouldnt exist without her and the LRB . Im grateful to her and her colleagues for all their editorial work.

Henry Finder at the New Yorker has been his usual distinctive mixture of brilliance and calm. I have been helped immeasurably by his commissioning and his editorial advice.

I am grateful to Lidija Hass for her invaluable sleuthing help.

I would particularly like to thank Sara Stefnsdottr for her assistance in Reykjavik. In Iceland I would also like to thank Rakel Stefnsdottr, Valgarur Bragason, Snorri Jnnson, Kri Sturluson, Helga Vala and Dai Inglfsson.

In Baltimore, Id especially like to thank Steve Hunter and Jean Marbella for their hospitality and advice. Id also like to thank Ann LoLordo, Fern Shen, Lisa Evans, Mary Waldrow, Tony Damazio and Philip Robinson.

At Penguin, I would like to thank Helen Conford, Richard Duguid and Peter James; at Simon and Schuster, I would like to thank Sarah Hochman; at A. P. Watt, I would like to thank Caradoc King and his colleagues.

I would also like to thank Fram Dinshaw, Rhomaios Ram, Nicholas Doisy and Richard Smith.

Earlier versions of passages in this book appeared in the London Review of Books , the New Yorker and the Guardian .

I would like to thank Atlantic for permission to quote from Simon Johnsons article The Quiet Coup and the Nobel Foundation for permission to quote Daniel Kahnemans autobiography.

1. The Cashpoint Moment

As a child, I was frightened of cashpoint machines. Specifically, I was frightened of the first cashpoint I ever saw, the one outside the imposing headquarters of the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank, at 1 Queens Road Central, Hong Kong. This would have been around 1970, when I was eight. My father, being an employee of the bank, was an early adopter of the cashpoint, which stood just to one side of the buildings iconic bronze lions, but every time I saw him use it I panicked. What if the machine got its sums wrong and took all our money? What if the machine took someone elses money by mistake, and my father went to prison? What if the machine said it was giving him only ten Hong Kong dollars but actually took much more out of his account some unimaginably large sum, like fifty or a hundred dollars? The freedom with which the machine coughed up its cash, and the invitation to go straight out and spend it, seemed horribly reckless. The flow of money, from our account out through the machine and then into the world, just seemed too easy. My dad would stand there grimly tapping in his PIN number while I hung on to his arm and begged him to stop.

My scaredy-cat eight-year-old self was on to something. The sheer frictionlessness with which money moves around the world is frightening; it can induce a kind of vertigo. This can happen when you are reading the financial news and suddenly feel that you have no grip on what these numbers actually mean what those millions and billions and trillions actually represent, how to get hold of them in your mind. (Try the following thought experiment, suggested by the mathematician John Without doing the calculation, guess how long a million seconds is. Now try to guess the same for a billion seconds. Ready? A million seconds is less than twelve days; a billion is almost thirty-two years.) Or it can happen when you look at a bank statement and contemplate the terrible potency of those strings of digits, their ability to dictate everything from what you eat to where you live the abstract numerals whose consequences are the least abstract thing in the world. Or it can happen when the global flow of capital suddenly hits you personally when your apparently thriving employer goes out of business owing to a problem with credit, or your mortgage loan jumps unpayably upwards and you think: just what is this money stuff anyway? I can see its effects I can thumb a banknote, flip a coin but what is it, actually? What do these abstract numbers stand for? What is the thing thats being represented? Wouldnt it be reassuring if it was more like a physical thing and less like an idea? And then the thought fades: money is what it always was, just there, a fundamental fact of the world, something whose coming and going is predictable in the way that waves are predictable on a beach: sometimes the tide is in, sometimes the tide is out, but at least you know that the basic patterns of its movement operate under known rules.

And then something happens to change your sense of how the world works. For Rakel Stefnsdttir, a young Icelandic woman studying for a Masters degree in arts and cultural management at the University of Sussex in Brighton, it happened early in October 2008. She stuck her card in the wall to take out some cash and the machine told her that the funds werent available. Rakel thought nothing of it. I know it goes through the transatlantic telephone line and that sometimes has problems, so I thought it must be that. A day or so earlier she had paid her first terms school fees on her card; she had been working in the theatre for a number of years before going back to do this MA degree, and she was comfortably solvent.

Weve all had the experience of sticking our card in the wall and not getting any money out of the cashpoint machine, because we dont have any money in our account. But what Rakel, and thousands of other Icelanders that day, were experiencing was something much stranger and more unsettling. Her cashpoint card was blanking her not because she didnt have the money, but because the bank didnt. In fact it wasnt just that the bank didnt have enough money, it was the Apocalypse Now scenario: her card wasnt working because Iceland had run out of money. On 6 October the government closed the banks and froze the movement of any capital outside the country because it was on the verge of going broke. By the time Rakels credit-card payment for her terms fees cleared, one day later, the Icelandic krna had collapsed and the amount she shelled out had increased by 40 per cent. It took three weeks for Rakel to regain access to her bank account, and by that time it had become clear that her course of studies was unaffordable. Shes now back home in Reykjavik, out of work, her entire Plan A for her future abandoned. What angers me most about our former government here, she says now, is that they didnt have the decency to be ashamed.

Thats what can happen when a countrys banks go bad. Some of the detail of the Icelandic case is exotic: basically, a small group of rich and powerful people sold assets back and forwards to each other and created a grotesque bubble of phoney wealth. Thirty or forty people did this, and the whole country is paying for it, a Reykjavik cab driver told me and Ive yet to meet an Icelander who disagrees with the thought. But although a small group of people were ultimately responsible for the bubble, the whole country was caught up in it, as a huge wave of cheap credit lifted Iceland into a kind of economic fantasyland. The banks were at the heart of this process. Icelands banking sector had been state owned until 2001, when the economically liberal Independent Party privatized it. The result was explosive growth fake growth, but explosive. A country with 300,000 people the population of Brighton and no natural resources except thermal energy and fish stocks suddenly developed a gigantic banking sector whose assets were twelve times bigger than the whole of the economy. There should have been a warning sign in the coinage, which is based on fish: the 50 cent coin has a crab, the one krna a salmon, the ten krnur a school of capelin, the 100 krnur a plaice. Thumbing the coins, you think: these guys know a lot about fish; about banking, maybe not so much.

Next page