BP BLOWOUT

INSIDE THE GULF OIL DISASTER

DANIEL JACOBS

BROOKINGS INSTITUTION PRESS

Washington, D.C.

Copyright 2016

Daniel Jacobs

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Brookings Institution Press.

The Brookings Institution is a private nonprofit organization devoted to research, education, and publication on important issues of domestic and foreign policy. Its principal purpose is to bring the highest quality independent research and analysis to bear on current and emerging policy problems. Interpretations or conclusions in Brookings publications should be understood to be solely those of the authors.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available.

ISBN 978-0-8157-2908-2 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8157-2909-9 (ebook)

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Typeset in Sabon and Gotham Condensed

Composition by Cynthia Stock

CONTENTS

PREFACE

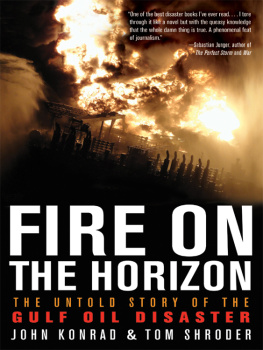

In 2010 a blowout occurred at one of BPs deepwater wells in the Gulf of Mexico, killing 11 people and causing more than 3 million barrels of oil to hemorrhage into the ocean waters over 87 days. The oil that surfaced and washed ashore across the five Gulf Coast states affected the lives of millions of people. The oil also killed tens of thousands of wildlife and caused severe damage to natural resources. By mid-2016 BP had set aside nearly $62 billion to cover the costs of the end resultsno small amount even for one of the richest companies in the world.

This is the inside story of the disaster and its aftermath. It is a story that has emerged more fully with time. Corporate homicide. The largest offshore oil discharge and the worst environmental disaster in American history. The most expensive manmade corporate disaster on record. All at the hands of one of the largest multinational corporations in the world. And all avoidable.

Although primary fault lies with BP, the federal government failed in its responsibility to oversee offshore drilling. To make matters worse, neither BP nor the federal government was prepared to cope with such a massive blowout. Both were ill-equipped to stop the flow of the oil from the well or to contain it once it reached the surfaceefforts on which BP reported spending more than $14 billion. The company and the government struggled with damage control on two fronts: the actual devastation and the perceived harm to their images.

The legal fallout was immense. Hundreds of thousands of private claims poured in, and the courts were flooded with lawsuits. The claims process became contentious, leaving both private parties and BP feeling cheated at times. Individuals and businesses who filed claims against BP for economic and property losses ultimately were awarded a total of more than $13.5 billion.

The federal government brought criminal charges against BP and four of its employees. The company pled guilty to manslaughter and other charges to resolve the criminal case, agreeing to pay a record $4 billion in fines and penalties. Two BP employees were acquitted, and two pled guilty to misdemeanors. No one will go to prison for the accident. In stark contrast, the federal government prosecuted hundreds of individuals for filing false claims against BP. Seventy-five were incarcerated.

The federal government also brought a civil suit against BP. The case was tried in New Orleans in three separate phases between 2013 and 2015. A few months after the trial ended, the civil suit settled for over $20 billion, much of which will go to the Gulf.

BP has paid a dear price financially for the disastera total of nearly $62 billionmore than any company has ever paid for a disaster of its making. Society also has incurred substantial costs, although these are more difficult to quantify precisely.

What lessons can be learned? From a broad business perspective, the disaster teaches us about the need for principled leadership, state-of-the-art risk management, and progressive sustainability practices. A company like BP could have afforded to have been the best in its classto have been a model in all three areas. It was not.

From a public policy perspective, the disaster teaches us that we need to take a fresh look at how much offshore oil drilling we allow in U.S. waters, especially deep water. We also need to develop a better means of deterring corporate conduct that gambles with peoples lives, livelihoods, health, and shared natural resources. Oil companies that abuse the privilege of drilling in U.S waters should risk losing that privilege, partially or entirely.

The BP Gulf oil disaster provides an important case study with equally valuable lessons in business, sustainability, and government.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I began and finished this book in California, my new home. Thanks to UCLAs Institute of the Environment and Sustainability, which hosted me twice as a visiting scholar, I was able to research and write in the company of distinguished scholars and amicable colleagues. I am especially grateful to Magali Delmas, director of the Institutes Center for Corporate Environmental Performance, and to Mark Gold, UCLAs associate vice chancellor for environment and sustainability. Heather Elms (my heroine) and Mark Clark, my former East Coast colleagues, provided invaluable mentorship over the years.

I am indebted to friends who generously took time out from their own busy schedules to support my effort in a myriad of ways. Ellen Spitalnik, Nicolas Kublicki, Mark Starik, and Murray Dry read and commented on early drafts. Jim Bayuk was not only a great sounding board, but also an unwavering source of reason and encouragement at every juncture. Susan Spinrad Esterly was both a superb listener and purveyor of sage wisdom.

My students have always been an inspiration to me. I was fortunate enough to have had the help of a number of excellent short-term student research assistants who managed to fit my work in with their studies. Leryn Gorlitsky, my long-term professional research assistant and now good friend, deserves special credit.

Some of the most interesting parts of the story would have been lost without my sources. Bill Reilly, my hero since the Rio Earth Summit, did not disappoint, and I became an instant admirer of Bob Graham. Jane Lubchenco, who invited me to her home on a Saturday morning, and Bob Bea, who stood outside a UCBerkeley parking lot to welcome me, overwhelmed me with their graciousness and their candor. So did others who prefer not to be named.

Last, I could never have gotten as far with this challenging endeavor (or in life) without the support of my loving familyimmediate and extended.

Thank you all.

MAYDAY IN THE GULF

At 9:53 P.M . on April 20, 2010, Andrea Fleytas sent a Mayday signal from the Deepwater Horizon , a mobile oil rig sitting some 50 miles off the coast of Louisiana in the Gulf of Mexico. The rig was connected to a BP oil well a mile down on the oceans floor. The well had suffered a blowout. When a well blows out, it can mean total loss of control, just like when a tire blows out on a car traveling at high speed. Fluids and natural gas shot up from the well, causing an explosion on board the rig, which became engulfed in flames. Disaster had struck.

Fleytas, a 23-year-old junior bridge officer, was a 2008 graduate of the California Maritime Academy. This was her first job on a vessel. She later reported that when she told the rigs captain about the distress call, he turned to her and cursed, asking: Did I give you authority to do that?

Next page