Table of Contents

Also by David Gessner

My Green Manifesto

The Prophet of Dry Hill

Return of the Osprey

Sick of Nature

Soaring with Fidel

Under the Devils Thumb

A Wild, Rank Place

To Nina, who lets me roamand come back

Firm ground is not available ground.

A. R. Ammons

I hear comments sometimes that large oil companies are greedy companies, or dont care, but that is not the case in BP. We care about the small people.

Carl-Henric Svanberg, former chairman of BP

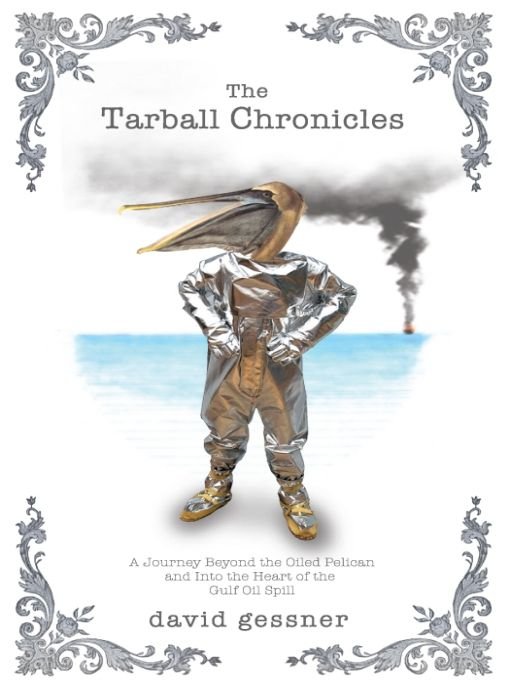

PRELUDE: INTO THE GULF

It is June and you are at a cookout at a friends house, a barbeque with all the kids playing in the backyard. You have just gotten back from traveling and you are happy to be home. For the last fifty-nine days millions of gallons of oil have been gushing into the Gulf of Mexico, but that is not your concern, not your problem. You want nothing to do with yet another dismal, depressing environmental story. You live in North Carolina and the Gulf is almost a thousand miles away. Yes, you care about the environment, so you should be thinking about the oil spill, but youve put on blinders, as you often do when the harsh light of big news events blares down on you. There is too much to think about, after all, and right now you are looking out at your daughter jumping on a trampoline, and the spill is the furthest thing from your mind. You drink your second beer and think that life is pretty good, pretty good indeed.

But then suddenly a friend is standing in front of you, and he insists on talking about the spill. He tells you of a live video stream he has seen from a mile below the surface and of the sight of a single curious eel peering at black-red goo pouring from the spills source, the busted Macondo well. He wonders what it is like for the people living down in the Gulf, and despite yourself and the beer and the sun on your face and your happy daughter playing, you start to wonder too. You should be down there, he says. You write about nature. You start to explain that that is not the kind of nature you write aboutyou write about birds and the coast, and you are not a journalist who chases stories. But then you stop explaining, and defending, and think simply: Maybe hes right.

Over the next week the idea builds in your head. Maybe the Gulf is where you should be. Summer plans, family plans, rearrange themselves in your brain. You have a somewhat strained talk with your wife about your new plans, and, since there is no other way to get there on short notice, you decide to drive. When will you go? your wife asks, and it turns out your answer is Right away.

A magazine gives you an assignment to cover the looming fall bird migration, but this is about more than birds, you know that already. When you finally decide to leave you do so in a mad rush, throwing everything in the back of your car and heading out without any real plan. Of course you are aware of the hypocrisy of traveling eight hundred miles in a vehicle powered by a refined version of the same substance that is still pouring out into the Gulf watersbut now you are driven. Now you need to see the oil. Youre not sure why. You have heard the Gulf called a national sacrifice zone, and maybe you want to explore this idea of sacrifice, of giving up some of our land, and our people, so the rest of us can keep living the way we do. So you go down, heading toward the Gulf.

Which gives you some idea of how I found myself sitting in a booth at an Applebees on the border of South Carolina and Georgia. My waiter, a chipper young man named George, asked me where I was heading, and when I told him, in a somewhat reluctant and grumbling fashion, I expected him to chirp Great! and hurry off to get my fries and beer. Instead he thought for a minute before launching into a little sermon.

We think its happening down there, he said, jerking his thumb behind him, toward the wall with the sports posters on it. But were part of it, too.

I snapped to attention.

Its all tied together, he said. The oil we use in our cars and the oil thats washing up on our beaches.

I felt like standing up and clapping. How did this George understand something that the major media outlets couldnt seem to grasp? It turned out this was another reason I had decided to throw everything in the car and head south. It seemed that no one in the national media was writing the bigger story, or at least the longer story, and I was pretty sure that the one oil-covered bird they kept trotting out for TV was not the story. No more bullshit was my blunt, businessman fathers favorite saying. No more bullshit indeed. This time around I would experience a story firsthand instead of letting the national media take me on its knee, like a kindly uncle, and tell me its sweet and homogenized version of the truth.

The next morning I drove through Georgia, mulling over my Applebees epiphany. My waiter reminded me of another natural philosopher, John Muir, who traveled this same route by foot nearly 150 years ago. When we try to pick out anything by itself, Muir said, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe. Yes... synapses snapped and connections crackled as the miles passed and I drank too much coffee. Wasnt the spill hitched to everything? Already the disaster seemed to be trying to teach me something, in dramatic fashion, a lesson that the world kept teaching me but that I had been slow to learn: on this planet nothing is apart from anything elseall of us, human, plant, animal: intertwined.

I drove all day. A friend in Mobile, Alabama, had offered me a place to sleep, and I had planned to go there, but then fate, in the form of weather, decided otherwise. A thunderstorm bullied me eastward, toward the Florida Panhandle, until I noticed a sign for a beach I had seen on the news a week before. That beach was known for its famously white sand, at least until the caramel sludge started washing over it. As I continued along the shore I noticed dozens of cleanup workers wavering through the mist like a ghostly prison crew in fluorescent vests, sweeping the sands. There were a couple hundred workers in all, and at first the scene made no sense, the people seemingly disembodied and floating. I soon learned that these workersmany formerly unemployed and mostly menwere being paid eighteen bucks an hour by BP to pick at the sand. I also learned that their job was to gather tarballs and toss them into huge plastic bags, then bring the bags to the command center where they were weighed and hauled away in trucks. Almost all of the workers were black, and I got the feeling that most of these men, many from the nearby city of Pensacola, hadnt spent a lot of time at this particularly touristy beach before the last few weeks.

The second level of commandthe sergeantsdidnt exactly look like beachgoers either. I pulled over and watched them for a while. Muscular but overweightalmost all white, incidentallythey barked orders and drove around in fourwheel-drive ATVs that looked like amped-up golf carts. At first I thought that they might enjoy their little taste of authority, but they never smiled. No one seemed to be having a good time.

Dont ask them any questions, the girl back at the beer store had told me. BP wont let them talk to civilians.