American Terroir

The Living Shore

Fruitless Fall

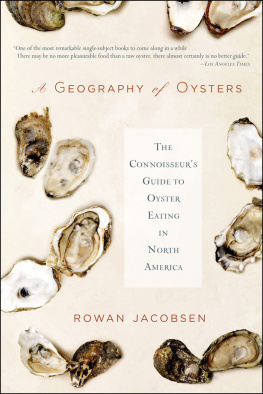

A Geography of Oysters

SHADOWS

ON THE GULF

A Journey Through Our Last Great Wetland

Rowan Jacobsen

Copyright 2011 by Rowan Jacobsen

Diagram on p. 56 copyright 2011 by Mary Elder Jacobsen

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner

whatsoever without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief

quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information address Bloomsbury

USA, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

Published by Bloomsbury USA, New York

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Jacobsen, Rowan.

Shadows on the Gulf : a journey through our last great wetland /

Rowan Jacobsen.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-60819-581-7 (hardback)

1. Natural historyMexico, Gulf of. 2. Coastal ecologyMexico, Gulf of. 3. Mexico, Gulf of. 4. Natural historyGulf Coast (U.S.) 5. Coastal ecologyGulf Coast (U.S.) 6. Gulf Coast (U.S.) I. Title.

QH92.3J33 2011

508.76dc22

2010051498

First published by Bloomsbury USA in 2011

This e-book edition published in 2011

E-book ISBN: 978-1-60819-700-2

www.bloomsburyusa.com

When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.

JOHN MUIR

CONTENTS

IN THE TIDE pools of Alabamas Grand Bay National Wildlife Refuge, on May 13, 2010, the water was alive and blue. Look at that turquoise! said Bill Finch, director of conservation for the Alabama chapter of the Nature Conservancy. Look at it! We were standing in a salt marsh in Grand Bay, crown jewel of Gulf natural areas, and squinting into a depression in the rushes. I leaned in close to watch an aquamarine trail streaking through the water like a shooting star. Look at that turquoise! Bill said again. Isnt it beautiful? How do I capture that on film someday?

We were watching male sailfin mollies. The minnow-size fish live close to shore and move into open pools in the rushes, where they can display for females without being eaten, turning sideways and making quick runs across the tide pool, catching the sun along special iridescent scales. It looked like they were flashing neon lights. God, thats stunning, Bill said. I could watch all day.

It was springtime on the Gulf Coastmating season. All around us, life was making new life, or at least contemplating the idea. The male sailfin mollies were nudging females toward the privacy of the reeds. Behind us on the salt pan, willets were flitting into the air and piping their pennywhistle love songs. A rail had just hatched her chicks in the cordgrass. At the edge of the marsh, acres of oysters were spawning. And farther out to sea, uncountable crab eggs were riding the warm Gulf currents. This was, normally, the most hopeful time of the year. And Grand Bay sure as hell looked normal. Miles of rush stretched to the Mississippi state line, backed by a wall of some of the only tidal pine forest on Earth. The sun glinted off waves rolling over vast seagrass beds. Beautiful.

But we couldnt enjoy it. If Bill wanted to capture the mollies on film, he had better do it today. Ten miles straight offshore from us, the first black cannonade of tar balls was splatting into Dauphin Island, the sandy barrier island that is the coasts first line of defense. Farther out, something dark and dead was gathering in the depths.

To the east, on the hazy horizon, we could just make out the buildings of Bayou La Batre, a small town that is Americas shrimp capital. In the movie, Forrest Gump keeps his shrimp boat in Bayou La Batre. The previous weekend the town had held the Blessing of the Fleet, the traditional opening of the fishing season. The decorated boats paraded past a priest, who blessed each in turn. But then, instead of heading to sea, the boats turned around and returned to their berths. No fishing on the Gulf.

I hope I have more time with Grand Bay, Bill said. With his gray beard, balding pate, and general demeanor, he gave the impression of being the Lorax of the coastan impression strengthened when he later leaped across the marsh, through knee-deep muck, to stop an airboat from plowing into the needle rush. Bill has sun-reddened skin and the kind of soft Southern drawl that has always put me at ease. Today, though, the softness of his voice made the alarming nature of his words stand out almost unbearably. I dont know that you will ever, ever see a salt pan like this anywhere else. Grand Bay is our model. If we want to know what the coast was like, we come to Grand Bay. There are all these community types, like this tidal pine forest, that just dont exist anywhere else anymore. This is just the very edge. You have to see the seagrass beds. You have to see the shell mounds. Not long ago, Bill had been out on those Native American shell mounds, on islands in the middle of the bay, shucking oysters straight out of the water and picking wolfberriesNorth American goji berries, delicious savory little fruits that grow on the moundsand grazing on glasswort, a salty, crunchy, asparagus-like plant. Its the way people must have eaten for ten thousand years.

In early April, the Nature Conservancys Alabama chapter had established a mile and a half of new oyster reef on Coffee Island, off the Alabama coast. It was the best oyster-restoration project this country had ever seen. It had seemed like a heartening success until the Macondo well beneath the Deepwater Horizon blew out on April 20 and sent a tidal wave of oil straight toward that reef. Id been interested in reef restoration for years and decided to visit those oysters a few days before the oil did. Bill and I got talking, and at every turn in the conversation he told me something new and surprising. Alabama has the greatest biodiversity of any state east of the Mississippi. Alabama has the greatest diversity of crawfish. Of freshwater fish and mussels. It has the greatest concentration of turtle species in the world . The entire Appalachian Mountain chain has twelve species of oak trees; Alabama has thirty-nine. I felt the scales of ignorance falling from my eyes.

Sensing a kindred spirit, Bill had brought me to Grand Bay, to see it as it was, before anything changed. Hed been coming here since he was a kid growing up in southern Mississippi in an old Choctaw town. In those days, it was just the scenery of growing up. I dont want to say you take it for granted, but you dont have a context for it. Now he had a context. You can imagine what happens when oil runs into this. Its just gonna stick to it. Its the gum-in-the-hair problem. Youll never get it out. But heres the real problem. Its gonna be coming in for a very long time, and some of its gonna be coming in on storm tides. If we were to get a storm tide that lifted it right over this marsh, that would really worry me.

It was only a few weeks after the blowout, but already it was clear that the thickest, tarriest oilthe stuff riding well beneath the surfacewould be coming in sporadically for years. When oil hits marshes, it chokes out the oxygen and nitrogen that the grasses need. The soil goes hypoxic. Then the marsh grass dies. Estuaries like Grand Bay are where 90 percent of the fish species in the Gulf come to breed. They are the nurseries of the Gulf. Whenever an acre of marsh grass dies, another acre of the Gulf dies.

We dont really know what breeds in these tide pools, Bill said. The young come in here for protection. Theres a real convergence of freshwater and saltwater species. In 2004, when Bill was an editor at the Mobile Press-Register, the reporter Ben Raines discovered a possum pipefish in Grand Bay, the only one seen in the Gulf in more than thirty years. The find scuttled an oil companys plan to drill for natural gas right in the heart of Grand Bay, which has the best remaining seagrass meadows possum pipefish require. It was found only in these types of habitats, Bill explained. And now it may be too late. Bill turned away from watching the mollies and stared out at the waves. He was speaking softly, as if to himself. I fall in love with these places way too easy.

Next page