Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2017 by Adley John Cormier

All rights reserved

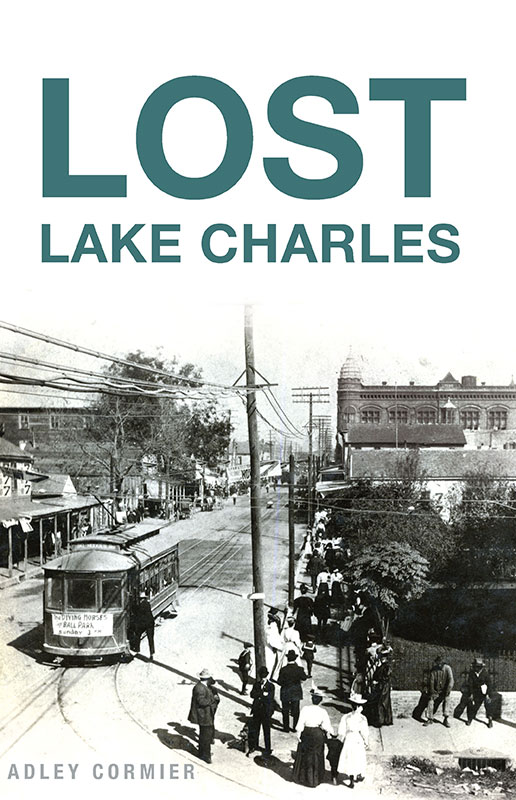

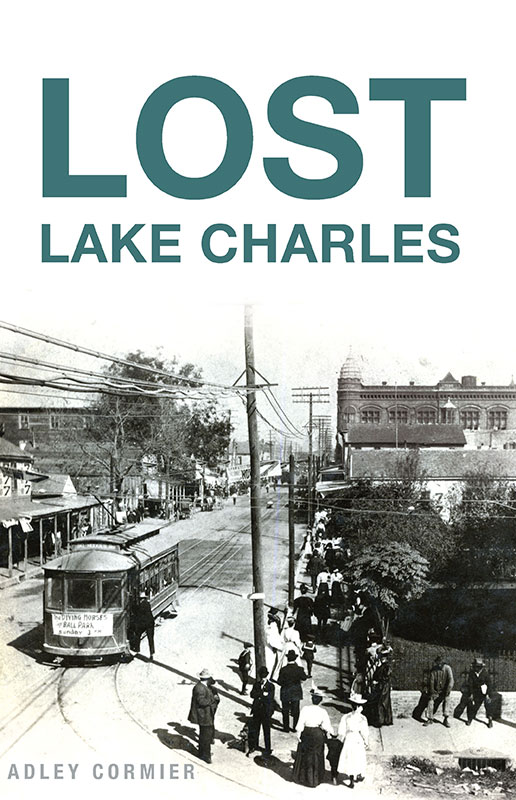

Front cover: courtesy McNeese University Archives.

First published 2017

e-book edition 2017

ISBN 978.1.43966.110.9

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017934926

print edition ISBN 978.1.62585.882.5

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and

The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Lost Lake Charles is dedicated to Melinda Antoon Cormier,

a woman of infinite creativity and boundless patience.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many sources were used for the research and writing of this book. While there are very few published academic histories of Lake Charles, there are literally hundreds of unpublished theses, newspaper and magazine articles and monographs on elements of Lake Charles history available at McNeese State University Frazar Library Archives and Special Collections, including the copious scrapbooks of Maude Reid, which provide a personal commentary on popular history, and the collections of the Calcasieu Parish Library at its Southwest Louisiana Genealogical and Historical Library branch at the Carnegie building in downtown Lake Charles.

In producing this book, the author acknowledges the additional research and the work, both published and not published (or now out of print) of the following historians and journalists: Lloyd Barras, Jim Beam, Robert Benoit, W.T. Block, Mark T. Carleton, E. Harper Charlton, Edwin Adams Davis, Stewart Alfred Ferguson, Louis C. Hennick, Mike Jones, Don Kingery, Donald Millet, Maude Reid, Nola Mae Ross, Ward Buddy Threatt, Joe Gray Taylor, Thomas Watson and T. Harry Williams.

Special acknowledgement is made to the archives of the Lake Charles American Press, whose online access of Lake Charles newspapers is complete to 1898.

Special acknowledgement goes to McNeese State University Archives and Special Collections at Frazar Memorial Library, and to Pati Threatt, archivist, for access to theses, scrapbooks, notes and reports, as well as for images as noted.

I want to give special acknowledgement to Imperial Calcasieu Museum executive director Susan Reed and curator Devin Morgan for images as noted.

Information about National Register of Historic Places properties, processes and nominations is from the websites of the National Register and from that of the Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation and Tourism.

Information about programs of the Calcasieu Historical Preservation Society (CHPS) is from the societys website and from minutes of the society.

Information about Louisiana Speaks, the Downtown Development Authority and the Historic Preservation Commission of the City of Lake Charles is from the minutes of the authority and the commission.

PROLOGUE

The best way to tell a story is to tell the whole story. To do that, you sometimes have to use props and pictures, offering evidence to prove a point more quickly and make that point more clearly. Actual, existing buildings make it easier to tell the whole truth when it comes to telling local history, which is, of course, the whole truth of a place.

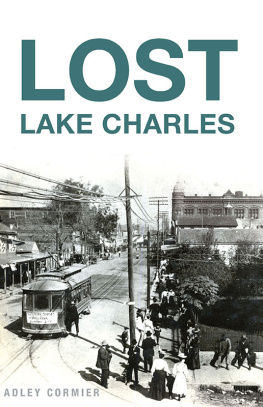

A 1920s view of palm-lined Broad Street, with the Kirkman streetcar in the middle ground. Courtesy McNeese University Archives.

In Lake Charles, Louisiana, a central fact of its history is that at one time there were lumber mills that processed pine and cypress. There is no tangible evidence of that great sawmill industry todayyou just have to imagine the mills on the shores and the logs floating on the water, the steam-powered saws ripping three-hundred-year-old cypress into boards around the clock. You certainly cant smell the sawdust and you cant sense the steam. In fact, the only legacy of the industry that you can actually see today are the many Victorian and Edwardian homes built from that very cypress and pine.

Another central fact is that for over thirty years a progressive Lake Charles had streetcars that served the entire community and operated around the clock! There is no evidence of that today. Gone also are the sailing schooners, the edges of lakes and waterways dark with cypress and tupelo loaded with Spanish moss, the ferry landings of the Rex and the Hazel and even the railroad stations that once tied this community to the world. Visual testaments of a rowdy and colorful past are all goneand now nearly forgotten.

This book will help you remember a history that you may never have known.

PREFACE

WHO AND WHAT WE ARE

In terms of Louisiana history, Lake Charles is a relatively young city. Natchitoches and New Orleansand more than a few other Louisiana cities and townshave a 100- to 150-year head start. But even taking that into consideration, Lake Charles has a colorful, complex and diverse history in many ways different from other communities in the state. For much of its existence, Lake Charless story is perhaps more typical of that of the boomand-bust American Wild West than that of the sleepy Deep South. The threads of distance and isolation, of independent action taken in the face of adversity and of ready access to the wild and the open may have colored the history of Lake Charles like no other city in the South.

Intrepid early pioneers developed a self-reliant culture of cattle grazing, subsistence farming, hunting and fishing rather than that of agrarian indigo, cotton or sugarcane plantations that was the standard pattern in the rest of Louisiana and in most of the South. With newcomers to the southwest Louisiana area, the cutting and processing of lumber became another source of wealth, followed in time by rice; by extractive industries like sulfur and oil; by transportation, refining and petrochemicals; and even by aviation. As soon as the area was connected by rail to the rest of America, the once isolated southwest Louisiana became the unique focus of one of the earliest large-scale land promotion schemes in North America. The search for an open and honest history that explores the untold and sometimes quirky saga of this corner of Louisiana is the purpose of this book.

The wild and lonely shores of Lake Charles can well be imagined from this image taken in the second half of the nineteenth century. Courtesy the Imperial Calcasieu Museum.

A PLACE OF NEIGHBORHOODS AND SMALL VILLAGES

Lake Charles is a place of neighborhoods and small villages. In city planning jargon, the map of the city reflects that of a poly-centered net, which means that there are multiple areas of community and civic focus scattered over a network of streets and roads. While some neighborhoods serve as places to live, others focus on retail, industry and business, hospitality and casinos, education, healthcare or government. As the city grew from its start on the lake, the direction of growth has been generally southward and toward the east, and now that growth has literally jumped over the Calcasieu River and English Bayou on the north, there is poly-centered growth in the Moss Bluff and Gillis areas, once viewed as the remote countryside.

Next page