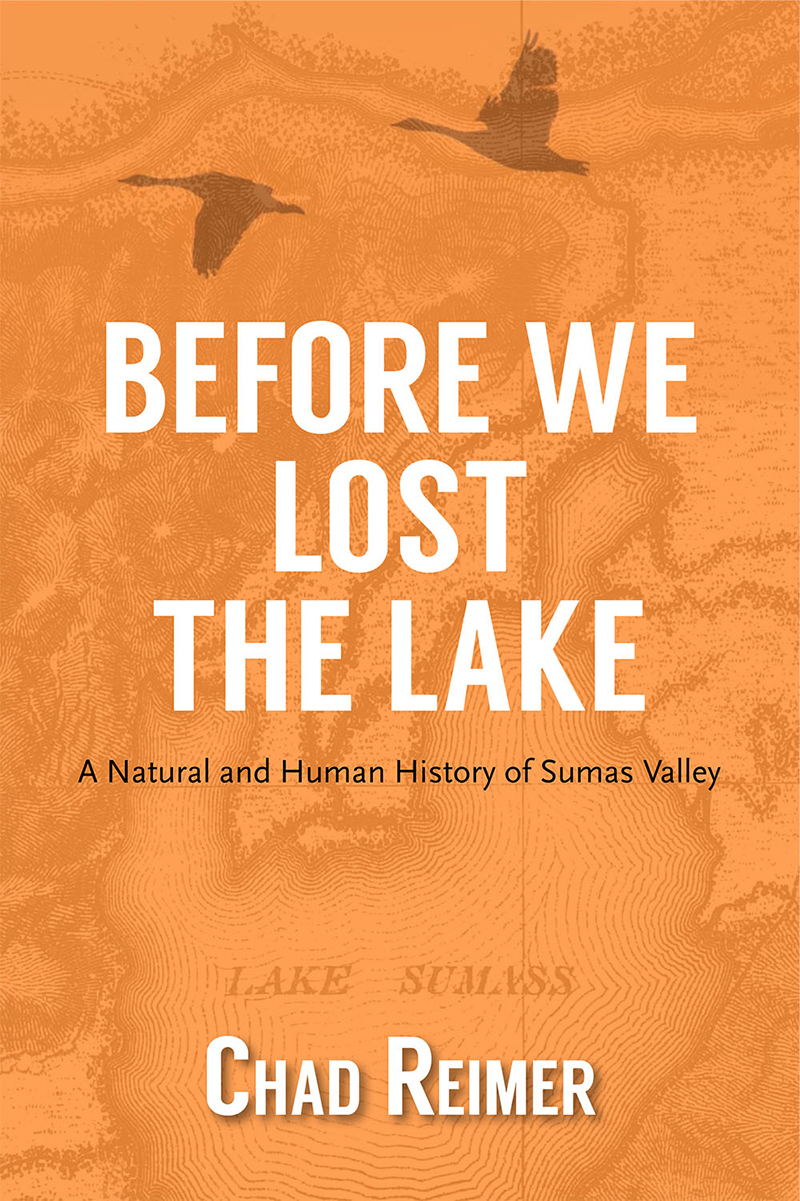

Before We Lost the Lake

Copyright Chad Reimer 2018

02030405062423222120

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the publisher or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright, the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency, .

Caitlin Press Inc.

8100 Alderwood Road

Halfmoon Bay, BC V0N 1Y1

www.caitlin-press.com

Text and cover design by Vici Johnstone

Printed in Canada

Caitlin Press Inc. acknowledges financial support from the Government of Canada and the Canada Council for the Arts, and the Province of British Columbia through the British Columbia Arts Council and the Book Publishers Tax Credit.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Reimer, Chad, 1963-, author

Before we lost the lake : a natural and human history

of Sumas Valley / Chad Reimer.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-987915-58-7 (softcover)

1. Sumas Lake (B.C.). 2. Abbotsford (B.C.)History. 3. Abbotsford (B.C.)Historical geography. 4. Sumas Prairie (B.C. and Wash.)History. 5. Sumas Prairie (B.C. and Wash.)Historical geography. I. Title.

FC3845.S92R45 2018911.71137C2018-903398-3

Before We Lost The Lake

A Natural and Human History of Sumas Valley

Chad Reimer

Caitlin Press

Contents

To Shannon

Acknowledgements

I have lived with this book for well over a decadefrom posing the first simple questions, through chipping away at the mountain of primary material, to the struggle of making sense of it all in writing. Along the way, I have benefitted from the professionalism and hard work of archivists and librarians from Victoria to Washington DC, for which I am greatly indebted. The reference staff at the BC Archives listened to my endless requests patiently and filled them promptly. The interlibrary loan department and Chilliwack circulation desk of the University of the Fraser Valley always delivered, no matter how large or obscure my request. It was an absolute delight to work in the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, and the staff of the map department went above and beyond the call of duty.

Closer to home, I want to thank the following individuals for their help: Tia Halstead at Sto:lo Nation Archives; Kris Foulds at Reach Gallery and Museum; Paul Ferguson of the BC Archives; Shannon Bettles of Ft. Langley National Historic Site; and Calvin Woelke at the Land Titles and Survey Vault. Vici Johnstone and the crew at Caitlin Press have been a joy to work with; their energy and courage know no bounds. My biggest debt is to my wife, Shannon, who never stopped believing this book would see the light of day.

Introduction

Driving east from Vancouver along the Trans-Canada Highway, past the monotonous stream of malls, box stores and subdivisions that is suburban sprawl, you reach the crest of an escarpment on the edge of Abbotsford. Looking below you see miles of flat prairie, framed between the towering Cascade Range to the south and Sumas Mountain to the north. The land is divided into a checkerboard of country roads, green fields and clutches of tidy farm buildings. For British Columbiawith its sea of mountains and arid interior plateausit is a rare sight, more reminiscent of the Prairies than the far west coast.

In need of a stretch, you exit at Whatcom Road, famed as the route taken by miners during the great Fraser River gold rush. A rest stop nestled along Sumas River appears; you pull in and, drawn by the glint of sunlight from a bronze plaque mounted on a pole, walk over to take a look. In the boosterish language of such things, the historical marker celebrates an engineering feat from a century ago: In 1924, by a system of stream diversions, dams, dykes, canals and pumps, 33,000 acres of fertile land were reclaimed from Sumas Lake. Only then do you realize that what you took as natural prairie was the bed of an extinct lake. And as you head back onto the freeway, you cannot shake a feeling of unease that the dry road stretching out ahead should be under water.

A century and a half ago, in early summer 1859, another visitor encountered the low and comparatively flat land of Sumas Valley, but it looked very different. After an exhausting journey by canoe and foot, veterinary surgeon John Lord pitched his tent alongside other members of the Northwest Boundary Survey. He recorded his impressions of the scene before him:

Our camp was on the Sumass prairie, and was in reality only an open patch of grassy land, through which wind numerous streams from the mountains, emptying themselves into a large shallow lake, the exit of which is into the Fraser by a short stream, the Sumas river.

In May and June this prairie is completely covered with water. The Sumass river, from the rapid rise of the Fraser, reverses its course, and flows back into the lake instead of out of it. The lake fills, overflows, and completely floods the lower lands. On the subsistence of the waters, we pitched our tents on the edge of a lovely stream. Wildfowl were in abundance; the streams were alive with fish; the mules and horses revelling in grass kneedeepwe were in a second Eden!

Few people today are aware that a sprawling lake once covered Sumas Valley, reaching all the way from Sumas to Vedder Mountain. Every spring, the lakes shores expanded even farther. In exceptional years, during high flooding, the waters stretched from Chilliwack into Washington State, forming a veritable inland sea. Sumas Lake and its surrounding wet prairies were rich with life, home to a dizzying array of plant and animal species. Natural grasslands spread out for miles on either side of the lake, massive sturgeon and runs of salmon prowled its waters, and countless waterfowl darkened its skies.

Yet the life story of Sumas Lake has never been told. The handful of historical works that have dealt with the topic have been limited in scope. For one, they focus almost exclusively on the lakes draining and the impact that had on the valley as a wholethey examine the lakes death, not its life. For another, they adopt one of two basic storylines: triumph or tragedy. The earliest literature shared the opinion of drainage proponents that the death of Sumas Lake was a triumph. As the first study concluded, the Sumas Reclamation Project took an 8,000-acre area of mud and wateran unproductive wasteland plagued by mosquitoesand turned it into as fine a stretch of farming country as one could wish to see. This view of Sumas Lake as a wasteland and the economic benefits brought by its dewatering prevailed in the following decades. It found expression in local histories up to the end of the last century.

Meanwhile, an opposing plot line has emerged, which refashions the story of the lakes early death as a tragedy. Authors of these works argue that the drainage project itself was poorly done, that its escalating costs outweighed the economic benefits and that the dream of an agricultural landscape of small family farms was never met. More pointedly, this literature has highlighted the negative effects of the lakes draining: the loss of a cherished natural feature; the environmental impact; and most importantly, the devastating damage it inflicted upon the Sema:th people, who depended on the lake for their livelihood.