Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

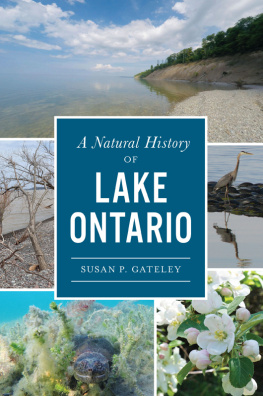

Copyright 2021 by Susan Peterson Gateley

All rights reserved

E-Book year 2021

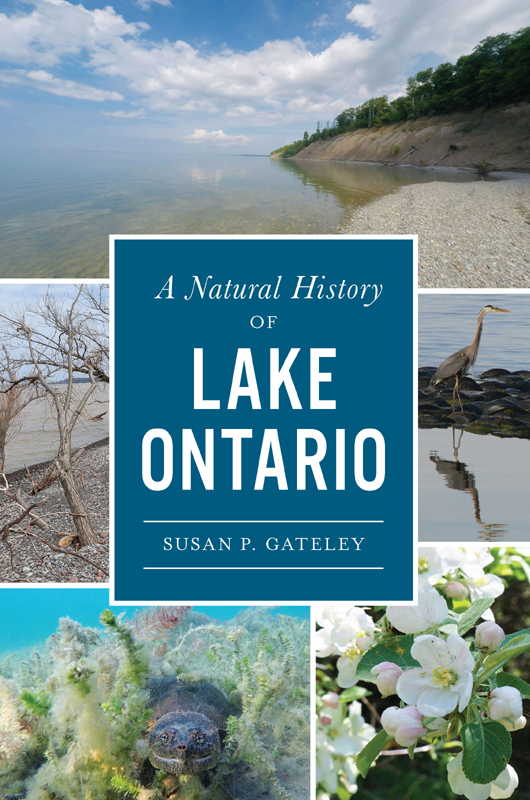

Front cover, top: author collection; all others: photo by Susan P. Gateley. Back cover: photos by Susan P. Gately.

First published 2021

ISBN 978.1.4396.7308.9

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021937065

Print Edition ISBN 978.1.4671.4792.7

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

In Memory of Roland Micklem a teacher and naturalist of compassion insight and humor

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many people have assisted in creating the knowledge that made this book possible. In particular, I would like to thank Nick Eyles, Diane Dittmar and Gerry Smith for fact checks. And I also must express my gratitude to Betsy McTiernan, Iria and Juha Cantori, Pat Campbell and Marsha Sawma, my fellow beach walkers, whose sharp eyes saw much that I missed. I also must thank Chris Gateley and his entire family of Ogden descendants, who made it possible for me to explore our amazing lake and its shores over the years.

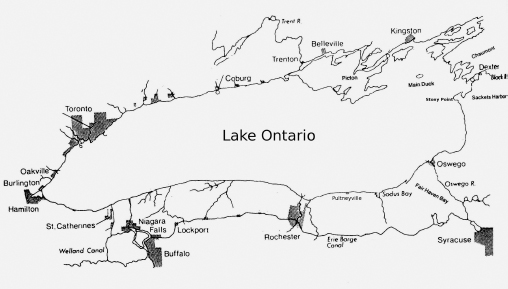

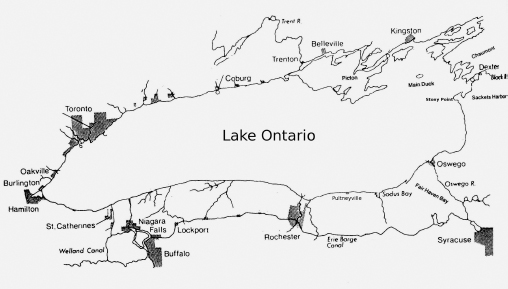

Map of Lake Ontario. Figure supplied by Chris Gateley.

INTRODUCTION

A LAKE LIKE NO OTHER

Does it have a tide? More than one person has asked this question on first viewing Lake Ontario. Its wide waters do seem almost oceanic, but they are not. Rather, freshwater lakes are among the most ephemeral of all geologic features. With a few exceptions, such as the Rift Lakes of Africa and Siberias Lake Baikal, the lives of the worlds lakes are no more than a brief blink on the planetary timeline. As soon as a lake is formed in Upstate New York, it begins to fill in to become a marsh, then a meadow and then a woodland. Nearly all of the worlds lakes are located in the northern hemisphere, where Ice Age glaciers formed them, and they are no older than the time of the retreat of the last glacier.

Surface fresh water accounts for an exceedingly small percentage of the worlds total water supply. Less than 1 percent of our water is contained in rivers and lakes, an amount roughly equivalent to a single drop in a bottle of wine. So the Great Lakes are truly a wonder and a gift to be treasured. They are the largest freshwater ecosystem on the planet and contain enough water to cover the entire United States to a ten-foot depth. Yet only about 1 percent of that volume is renewed each year. If more than that amount is removed or diverted for irrigation or some other purpose, lake levels will drop permanently.

Lake Ontario, the smallest by surface area, is unique among the Five Sisters. It alone was once connected directly to the sea, and for a time, as the glacier retreated, marine animals were able to travel up the St. Lawrence River to reach its basin. Fossil remains of marine seals and fishes and invertebrates from ten thousand years ago have been found in southern Quebec and eastern Ontario Province, marking the presence of a saltwater Champlain Sea. During this time, several marine species, including the deepwater sculpin and the Atlantic salmon, made their way into Lake Ontario. Our lake is also unique among the Great Lakes in that much of its economic and cultural history is dominated by Canada rather than the United States. The French first settled Upper Canada (Ontario Province in 1673) well before British settlement on the south shore at Oswego, and today, more than 20 percent of Canadas population resides within a few miles of the lakes shoreline. In this corner of the continent, Canadians outnumber Americans by about ten to one.

Lake Ontario, the smallest of the five Great Lakes, still ranks in the top twenty of the worlds freshwater bodies at number fourteen. Author collection.

Events on Lake Ontario, the Niagara River, and neighboring Lake Erie helped spark federal legislation to protect Americas waters nationwide. The Clean Water Act; the Toxic Substances Control Act; and the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (commonly known as the Superfund Act) were all crafted in large part after events in our region raised awareness of the dangers of various forms of pollution to human health. And that legislation and regulation also cleaned up some of the worst toxic messes in the Great Lakes watershed. Today, Lake Ontario faces a new set of challenges to its ecological well-being. But dozens of organizations and thousands of individuals are working to protect our inland sea. While plenty of threats to the lakes health remain, progress and healing have taken place, and this is still a place of incredible beauty filled with abundant life. And you can still watch those creatures, from tiny midges to soaring eagles and mighty sturgeon, as they continue to weave the web of life in and around one of the greatest lakes in the world. So slip on your walking shoes, cast off the dock lines to set sail or head for the nearest swim beach and enjoy a lake like no other.

THE AGE OF ICE

Lake Ontario lies in a land shaped by ice and water. Ours is a topography of kames, moraines, kettles, drumlins and prehistoric beaches. The vast ice sheet that covered this area ten thousand to twenty thousand years ago continues to impact us today. When the farmer discs and plants his field with the rocky knoll and the sandy patch of soil, or when the gardener or the hole digger struggles with cloddy sticky clay, they are reliving that glacial history. And those of us who rely on a shallow well for our drinking water may be benefiting from the last Ice Ages deposits that now form our aquifer.

The last major advance of ice here began about eighteen thousand years ago. At their maximum extent, glaciers completely covered all of present-day Lake Ontario and extended just south of Cayuga and Seneca Lakes. Studies suggest that when it finally melted, the ice retreated considerably faster than it had advanced. Nor was the retreat a simple one-way action. There were milder spells and colder times when the ice paused or even re-advanced some distance.

No one really knows for certain what caused that first unusually cold, snowy year when spring never came. Perhaps it was massive volcanic eruptions, like that of 1815, the year without a summer, when Tamboro erupted in the East Indies and blew two hundred cubic kilometers of earth into the air, sending enough ash into the atmosphere to block sufficient sunlight to tip the delicate global balance toward cooling. Or perhaps fluctuations of solar energy output or wobbles in earths orbit triggered the Ice Ages. In any event, glaciers form from snow. And the heaviest snowfalls occur at temperatures not far below freezing, so it only took a slight drop in the overall average temperature on earth to initiate the last Ice Age. Geologists dont know for certain what triggered the last Ice Ageor its end. But we do know that profound shifts in climate can occur with staggering speed. Some studies suggest that the Ice Age ended with massive floods as the planet warmed over a period of as little as a decade or two.

Next page