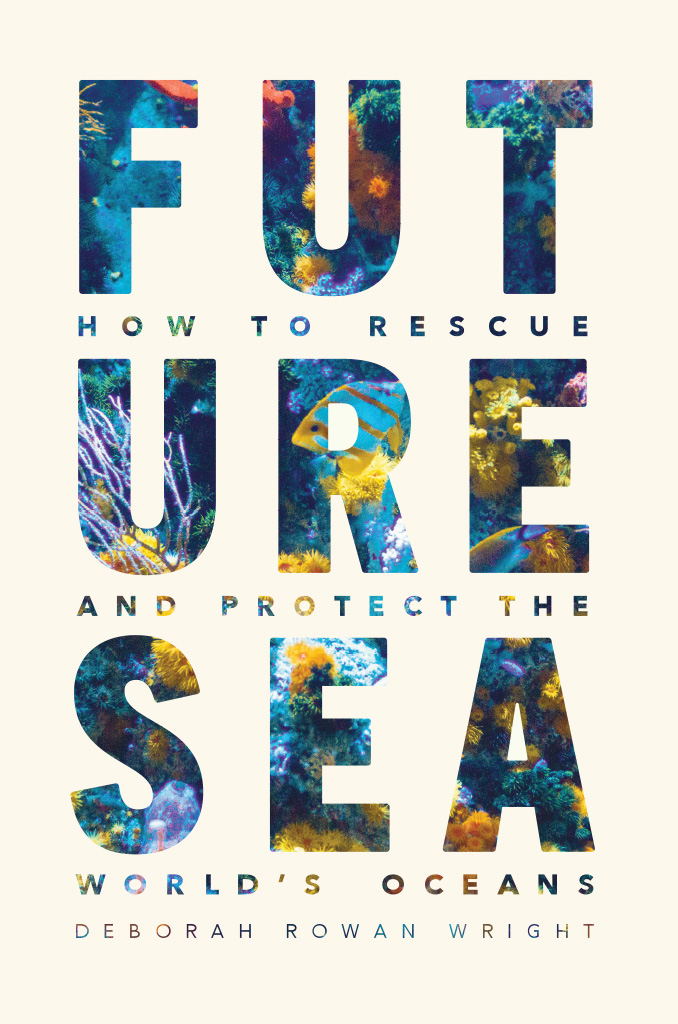

Future Sea

FUTURE SEA

How to Rescue and Protect the Worlds Oceans

Deborah Rowan Wright

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2020 by Deborah Rowan Wright

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2020

Printed in the United States of America

29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-54267-6 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-54270-6 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226542706.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Wright, Deborah Rowan, author.

Title: Future sea : how to rescue and protect the worlds oceans / Deborah Rowan Wright.

Description: Chicago : The University of Chicago Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020024360 | ISBN 9780226542676 (cloth) | ISBN 9780226542706 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Marine ecosystem health. | Marine habitat conservationGovernment policy. | Marine habitat conservationLaw and legislation.

Classification: LCC QH541.5.S3 W75 2020 | DDC 577.7dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020024360

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

For Ellie, Lydia, and Betty

Contents

Steep green slopes of red cedar and Douglas fir tumble down to Johnstone Strait, a stretch of the Pacific separating Vancouver Island from mainland Canada. This place is a gift for the eyes and the heart: an unruly expanse of forest cradling a flickering sea, with a sweet, clean chill in the air. The water is deep, and I am perched precariously upon it in a small boat, setting out on a whale-watching trip with my two daughters and my niece. We are heading south from Telegraph Cove, leaving the pale peaks of the Pacific Ranges melting into the distance beyond Blackfish Sound.

I stand swaying on the deck, feeling inconsequential in the hugeness of this land, this sea, and this sky. Wayward strands of wet hair cling to my cold face. Against the headwind we look over the bow and down into the shifting darkness below, wondering. Today we hope for a lot. They say theres no better place in the world to see the magnificent orcas.

Our fellow passengers stay in the cabin, sheltering from the drizzle and the wind. Up in the wheelhouse, Captain Wayne is at the helm and biologist Kyle is at the microphone, talking about waterproof trousers, hot coffee, and salmon runs. His voice is snatched away by the bluster outside and I catch only bits, so I listen harder. Hes listing the wildlife were likely to see. I hear bald eagles, humpback whales, dolphins, sea lions and, last, orcasotherwise called killer whales. Kyle explains that orcas arent whales at all, but the largest species of dolphin. They live in complex matriarchal family groups, with up to four generations in a single pod. There are two distinct types in this part of British Columbia: the transient Biggs orcas that roam widely along the Pacific coast, feeding on marine mammals such as dolphins and seals, and the resident orcas with an entirely different diet, primarily Chinook salmon. My mind drifts to what could be swimming under us. Will the fabled strait deliver?

A flurry of Bonapartes gulls gather above, on the lookout for lunch, as we make for the Michael Bigg Ecological Reserve along the coast at Robson Bight. This is a small chunk of protected land and sea that is off-limits to the public. It includes a swath of water and foreshore where orcas have come for generations to socialize and rub their bodies on the pebbles to scrape off barnacles. Were told theres a good chance of seeing them here. Suddenly the three girls squeal, bouncing and pointing like maniacs. Theyve spotted a surge of Pacific white-sided dolphins ahead, weaving through the water in unison, arching and diving in a lather of speed. We jump up, beckoning the others to leave the cabin, but within a few moments the dolphins are gone, leaving behind only trails of white water.

As our boat nears the reserve Captain Wayne cuts the engine so as not to disturb the animals, and we rock to the rhythm of the waves. Everyone is out on deck now, all eyes fixed on a stretch of water where the ridge falls into the bight, many with binoculars pressed to their faces. We wait and wait, watching expectantly. The rain lets up and clouds dissolve to reveal a backcloth of blue sky, but the orcas dont come. Rumbling disappointment is quickly dispelled, though. Kyle announces that the captain of another whale-watching boat has alerted him to a pod of orcas foraging for fish in the riptide about a mile farther south. We set off immediately.

Within a few minutes we see a strip of troubled water ahead, effervescent with currents clashing below. A great number of noisy birds dive to pick off fish caught in the fighting tides: rhinoceros auklets, common guillemots, and a variety of gulls. The boats engine goes quiet and we stop, bobbing on the swell. The first sign that orcas arent far away is a tall column of water vapor shooting up near the shore. Soon after, much closer to us, a glossy dorsal fin pierces the surface to yelps of joy on deck. Then, without warning, another orca emerges right next to the boat with a roaring swoosh as he breathes out, sending up a salvo of spray that makes us all gasp. Its a large male with a dorsal fin five or six feet tall. He glides past effortlessly on the port side and slips back downsix tons of bone, brains, and blubber wrapped in a mighty black submarine body.

By the time people move across the deck to watch, more orcas appear on the other sidea group of four, including a mother and calf. They are leaving the riptide banquet in a playful mood, circling each other, scribbling patterns in the water. They slap their tails down hard, making a distinct crack as the flukes hit the sea. The big male joins them and rolls on his side, lifting a pectoral fin as if to greet his family with a high five. We cheer and clap. Three more orcas rise together, their fins slicing the waves like knives cutting through rippling silk. People hardly know where to stand, afraid of missing something. The dolphins are back. They move toward us at a frantic pace, some leaping clear of the water, churning the surface into a froth as they swerve around the orcas. But now the orcas begin to head off, and the spectacle is coming to an endnot before an encore, though. The last to go is a large female. Suddenly she rises upright to get a good look at us, with a third of her body clear of the water. After a few moments her curiosity is satisfied. Obviously we arent all that interesting. She sinks back down and is gone, leaving us jumping, laughing, and clapping like excited children.

A posse of boisterous Dalls porpoises escorts us back to Telegraph Cove. They are surfing in the wake of the bow with frenzied energy, so close to the keel that when I lean over the side I can almost touch them. A bald eagle breezes overhead as we approach the harbor. Its the end of the trip. I gaze wistfully along the strait, then smile as I decide to do it all again the next day.

This region is rich in marine life. The inlets and coves, channels and deep fjords provide unique habitats and diverse ecosystems for a wide range of species: plants, fish and crustaceans, birds and mammals. A combination of ocean currents, eddies, and upwellings makes the waters very productive, and so much food brings in a host of hungry predators. But despite the high probability of seeing orcas in Johnstone Strait, the northern resident population is quite smallroughly three hundred individualsand there are only about seventy southern resident orcas, which live in the Salish Sea about two hundred miles farther south. Scientists are unclear on why the number of orcas remains low, and various explanations have been put forward. During the 1960s and 1970s many orcas were captured and taken to zoos and marine parks like SeaWorld. They are long-lived animals and slow to reproduce, and it takes many years for their numbers to recover. Thankfully Vancouver Islands orcas are protected by Canadas Species at Risk legislation and can no longer be whisked away into captivity, but there are other threats to their long-term well-being. Waterborne and airborne pollutants from agriculture and industry known as persistent organic pollutants reach the sea and contaminate the fish that orcas and other marine mammals eat, undermining the animals health and strength. The concentration of these toxins in the body increases at every stage of the food chain, so top predators like orcas have the highest levels.

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).