2004, 1987 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska

Preface to third edition 2018 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018933516

ISBN 978-1-4962-0751-7 (electronic: e-pub)

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

To Blue

Illustrations

page 2

following page 88

Preface to Third Edition

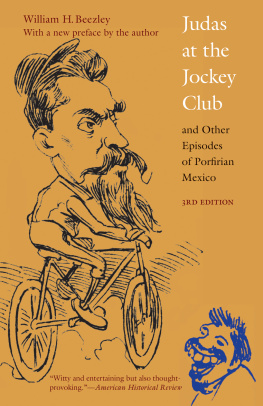

The third time around! Who would have thought that the story, captivating as it is, of the popular practice of creating papier-mch images to burn or explode on Easter Saturday or Sunday would result in the third edition of a book?

These effigies meant to be ephemeral have become collectible to individuals interested in the handicraft arts of everyday life. This is a rather recent development, although Frieda Kahlo and Diego Rivera did save and display two in the 1930s in the Blue House. The Judases have also appeared in museum exhibits of popular celebrations; the Museum of Popular Culture in the Coyocan neighborhood of Mexico City has a collection of Judases from as early as the 1960s. The collection includes hippies and other counterculture figures, such as young women who violate social standards (La Seorita Silicn, for example); the brokers of pawn shops, who according to tradition are Spaniards; Uncle (To) Sam; the charros of the official party agencies; state governors such as Guanajuatos Vicente Fox (who later was elected president); and President Carlos Salinas de Gotari. Other Judases have represented national issues such as drug usage, corruption, pollution, and potential environmental threats such as the Laguna Verde Nuclear Power Plant.

The Judases themselves have evolved somewhat. Some have become

The book itself has also evolved in its relationship to the history of the era of Porfirio Daz. Themes merely mentioned in its pages have become the subjects of fascinating investigations by other historians, and topics that are only alluded to here have stirred the imaginations of other scholars. These studies have examined foreign colonies in Mexico (especially the U.S. group) and their impact on the drive for cosmopolitan culture; sport and physical education and their part in the discourse of masculinity, dramatically with lower-class men and expressed in love letters; the seizure of indigenous properties and rapacious capitalism; the development of the army and organizational discipline; the promotion of modernization projects and insertion of technology into cultural practices; and the use of monuments to express the values of the regime.

This literature has provided significant investigations of non-elite aspects of Porfirian life. Together these works create a rich cultural, social, and economic context for the Judas burnings, and they offer The destruction of Judases served (as it still does) as a measure of the opinions of popular, lower-class, and marginalized groups. The Judas burnings represent the people of the pueblo and reveal their playfulness, their resistance to those whom they oppose, and their belief that public censure has meaning and import.

Another scholar, Adrian Masters, has extended the topic to Costa Rica and examined Judas burnings there. He did this in Judas and the Gentlemen of the Legion of the Ear: Modernization and the Judas Burning Rituals in Liberal-era Costa Rica. The essay formed part of his graduate work at the University of Texas.

Most certainly this book over the years has confirmed my commitment to a stochastic methodology for history. This approach creates an expectation that from somewhere will appear the random individual, event, or practice that will upset the clear lines of evolution, society, family, or culture. As the novelist Kurt Vonneguts character the king of Michigan says, history only prepares us to be surprised and then to be surprised again. Or if we think of this methodology in music terms, we can turn to the 2016 Nobel Laureate for Literature, Bob Dylan, who expressed it in lyrics as a simple twist of fate. That certainly was the case here: I stumbled on Judas figures and Judas burnings while reading foreign travelers accounts, newspapers, and official sources including consular and police reports. The widely common practice had no scholarly literature; this book was the first analysis of the topic. This methodology draws practical inspiration from the cultural anthropology of Clifford Geertz, Victor Turner, and Pierre Nora, from the literary history of Mijail Bakhtin, from members of the Anales School, the cultural history of various authors, especially Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, and, of course, from Carlo Ginzburg.

Since first writing the book, the greatest change has come with the internet and digital technology. These have resulted in, among many other things, the widespread availability of pictures and videos that individuals can view, edit, manipulate, and reconstruct to better understand Judas burnings. With this in mind, for the first time the University of Nebraska Press offers a manual with internet links, additional readings, and practice experiences that can be used in class or by anyone who wants to go beyond the chapters of this book. This manual is accessible through the University of Nebraska Press website.

Since beginning the initial research for this book, I have attended Judas burnings, visited cartoneros who make the Judases, discussed fiestas, and debated popular culture with many friends and colleagues in Mexico. Of these, I must mention Guillermo Palacios and Josefina Vzquez at El Colegio de Mxico; Claudia Agostoni and Elisa Spectman at the Instituto de Investigaciones Histricas, la Universidad Nacional Autnoma de Mxico; and two outstanding historians of popular culture, Carmen Nava (UAM-Xochimilco) and Ricardo Prez Montfort (CIESAS-Tlalpan). This edition has required the assistance and direction of Bridget Barry, my editor at the University of Nebraska Press. These individuals and dozens of artisans who make Judas figures have had an impact on my thinking not just in this book but in my efforts to understand and appreciate Mexicos vibrant culture, which remains in the face of expanded mass media and intense globalization endlessly fascinating.

The publication of Judas at the Jockey Club in 1987 marked the introduction of a cultural history volume that became a classroom standard and inspired other monographs examining Mexican daily life. A second edition of the book (2004) corrected some nagging typographical errors and expanded some information, but generally as the author I resisted the temptation to write a new book with the same title. A Spanish version of the text (2010) allowed some tinkering as well and expanded references to other festival studies. Now as the volume marks its thirtieth (or pearl) anniversary, letters and emails have again pointed out the need for some corrections. One of the most interesting came from Julio Gonzalez-Gallego, president, Lakeside Club de Remo Ac, correcting the title of the Lakeside Rowing Club. Another email from Chris Davidson of Hampshire in the United Kingdom added fascinating information about his great grandfather, Richard Honey (18391913), who was one of the five foreign founders of the Jockey Club and also a member of the Reforma Athletic Club. The message added that Honey had emigrated to Mexico from Cornwall in 1862 and founded iron Additional information also came through the opportunity to participate in two educational television projects, one a ten-episode series on the history of sport in Mexico and the second the history of the bicycle in the nation. Both of these appeared on Canal 11 and can be accessed through the video archives.

Next page