This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

2019 by Indiana University Press

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Cataloging information is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-253-04376-4 (hardback)

ISBN 978-0-253-04379-5 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-253-04378-8 (ebook)

1 2 3 4 5 23 22 21 20 19

T HIS BOOK IS THE RESULT OF A TWO-DAY workshop, People versus Humankind, held at All Souls College, Oxford, to which thanks are due for its hospitality and funding. Additional support was provided by St Johns College and the Institute for Social and Cultural Anthropology, both also at Oxford. The workshop was instigated by Morgan Clarke, Walter Armbrust, and Judith Scheele, to mark Paul Dreschs retirement from Oxford by a gathering of his advisees, colleagues, and friends; it could not have taken place without the help and advice provided by Melinda Babcock. Additional thanks are due to Nick Allen, Elizabeth Ewart, Tim Jenkins, and Tom Lambert, who provided invaluable feedback as discussants at the workshop. We are also grateful for the commentary provided by two anonymous reviewers of the original manuscript, and to Dee Mortensen, our editor at Indiana University Press.

If not a Festschrift of the traditional kind, this volume is intended to engage with and celebrate the workand the inspirational teachingof our common mentor, Paul Dresch. His aversion to limelight is now legendary, so we thank him for indulging our efforts. In the end, the ideas and the personal influence were harder to tell apart than we thought they would be. We thank Paul for that, too. In whichever way we came to be Dresch students, wherever it led us, and whatever we took away from it, it was an experience that changed our lives.

As an anthropologist one tries to make intelligible, to oneself and others, forms of human life. These are complex, for they conjoin many subjectivities and by definition no one account is adequate; yet they possess a certain objectivity despite this, for, at the least, there is a choreographed circulation of words, images, made things, formulae of interaction in which people build some enduring sense of shared position. Whether clustered in a village or spread across the internet or family visits, the imageries that characterise such particular lives involve currencies of reference held partially in common and forms of interaction which are, as the saying goes, second nature. (Dresch and James 2000, 7)

If theory is active, fieldwork is also rich in theory, because it produces what might be called moral knowledge, both ordering and revisable, intervening and reflecting, acting and comprehending. (Jenkins 1994, 452)

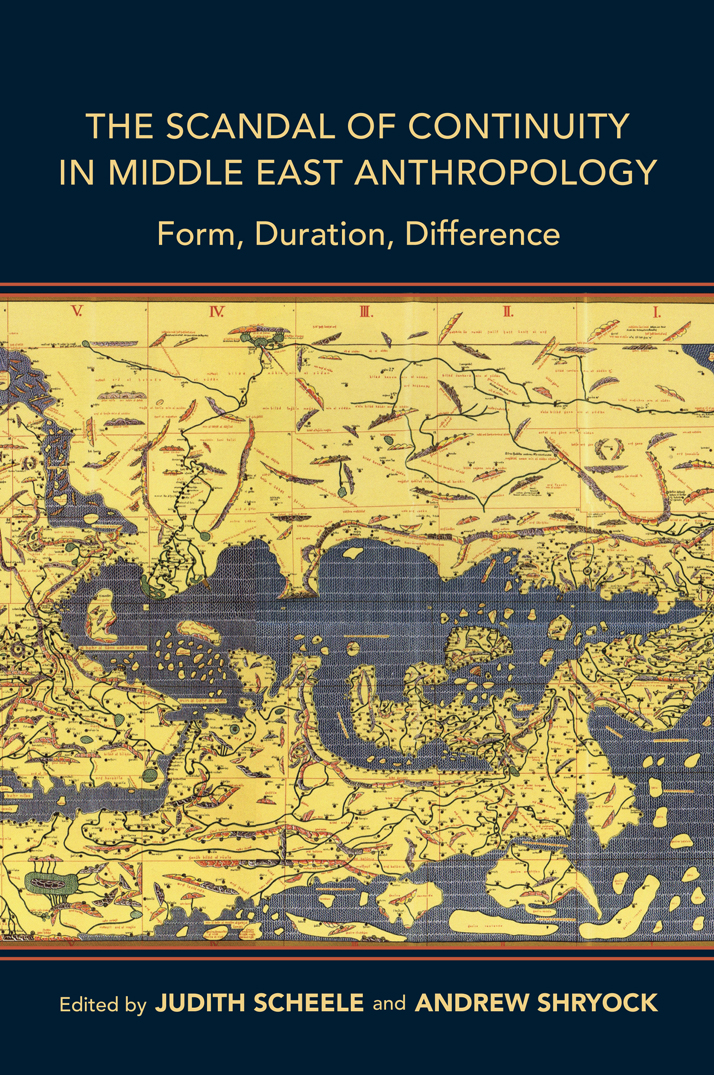

I T IS NOTORIOUSLY DIFFICULT TO DESCRIBE WHAT ANTHROPOLOGISTS do. Under pressure, we often tell curious interlocutors that we study customs and traditions or that we live with people to learn about their culture. We cringe as we speak these words. The truth is much harder to explain; it would take too much time, and it would probably make less sense. Besides, we hardly agree among ourselves about what we do or why. We go into the field looking for many things. What is surprising about fieldwork, as method and experience, is the remarkable degree to which it has remained, over the history of the discipline, a reliable way of producing anthropological knowledge, however contested that knowledge might be. In this volume, we make the case for a particular way of constructing knowledge that derives its strengths from an old and ongoing encounter of scholars, a discrete set of ideas, and a region of the world. It draws on early twentieth-century French social theory, the Oxford anthropology of the 1960s and 1970s, and a diverse body of ethnographic work located mostly in the Middle East, in Muslim societies, and in the political contact zones around and within them.

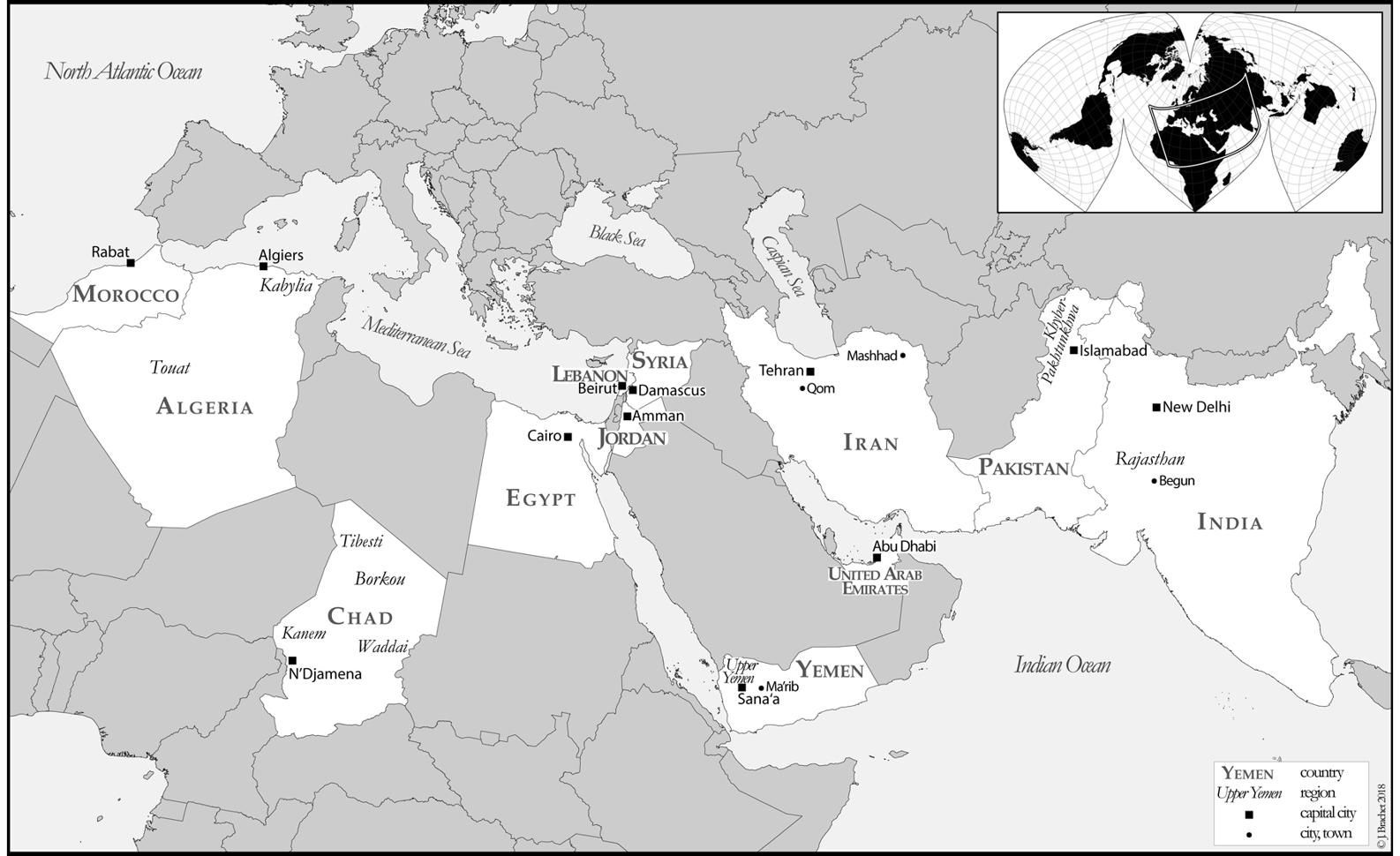

The Middle East is a world of part-worlds, of polities and economies that are internally differentiated and arrayed in elaborate hierarchies of interdependence. It long has been so. This might be one of the reasons why the anthropology of the Middle East tends to feel marginal to a discipline that historically drew strength from its embeddedness in worlds that seemed coherent and freestanding. Anthropology has turned away from these worlds, noting that, although images of self-sufficiency and stasis might at times correspond to local self-perceptions, they had little historical and have even less contemporary reality. This recognition was overdue but also troublesome. Arguably, it has undermined the intellectual confidence of the disciplinewhat, apart from local knowledge and ethnographic fieldwork, makes us special? More importantly, it has handicapped us in relation to our traditional interest in ordering principles, the constructs that make human life intelligible, give it regularity and form, and help us understand how it changes over time. In this volume, we argue that Middle East anthropology, which is undertaken in societies that are highly distinctive yet seldom neatly boundedwhere part-worlds, assertions of autonomy, widely shared ordering principles, and crosscutting patterns of inclusion and fragmentation in fact go togethermight hold lessons for the discipline as a whole.

In 1951, Evans-Pritchard, who emphatically was not a Middle East specialist, wrote that an anthropologist must have, in addition to a wide anthropological knowledge, a feeling for form and pattern, and a touch of genius (1951, 82). More modestly, we argue that renewed attention to patterns of continuity, both temporal and spatial, will allow us to develop a more sophisticated and deeply historical approach to worlds that are filled with form and pattern but have never been self-contained. It will also encourage a much-needed reconsideration of how metropolitan categories of thought interact with local concepts, categories, and forms of actiona process that itself may produce, as Dresch and James suggest, an enduring sense of shared position (2000, 7). In the end, what we call for is not a particular approach to theory or method but a mode of analytical engagement that moves constantly beyond its own privileged categories and into the world.

The Modern Imperial Frame

David Pocock (1961, 105) captured this sensibility when he wrote that anthropology is a dialogue of three: the anthropologist, the discipline, and the society studied. The subject matter of this exchange is not limited to local knowledge, or theory, or the analysts position. Rather, the dialogue grows out of assumptions, often unspoken at first, that slowly become intelligible as the parties to this conversation interact in depth and across difference. Whether they happen in remote field sites, at home, or in the archives, such conversations lead to the recognition of ordering principles: shared ideas, meaningful patterns of action and comprehension, recurrences, durable trends, and what earlier generations of anthropologists called structure. The word has since fallen out of use, mostly due to associations with functionalism and stasis. Nonetheless, it is clear that fieldwork is not simply a collection of data, as one might pick apples from a tree; it is more about figuring out the categories and frames that make things appear as data in the first place. One must reflect in order to measure, not measure in order to reflect, wrote Bachelard (1938, 213), famously, though hardly with anthropology in mind. It follows that ethnographers must constantly step back from their conversationsthose happening across the discipline and in fieldwork settingsto take in what is being said, a complicated maneuver that requires the creation of reflective spaces that feed back into the dialogue. The point is not simply to participate in a conversation or observe it, but to analyze it, to make extra sense of it. The structure that emerges is as much a product of this interpretation as it is of things experienced directly in the field. Distinguishing cleanly between these two realms is impossible; the meta is built into empirical analysis, and vice versa. Evans-Pritchard assumed as much, long ago, when he said that the theoretical conclusions will be found to be implicit in an exact and detailed description (1973, 3).