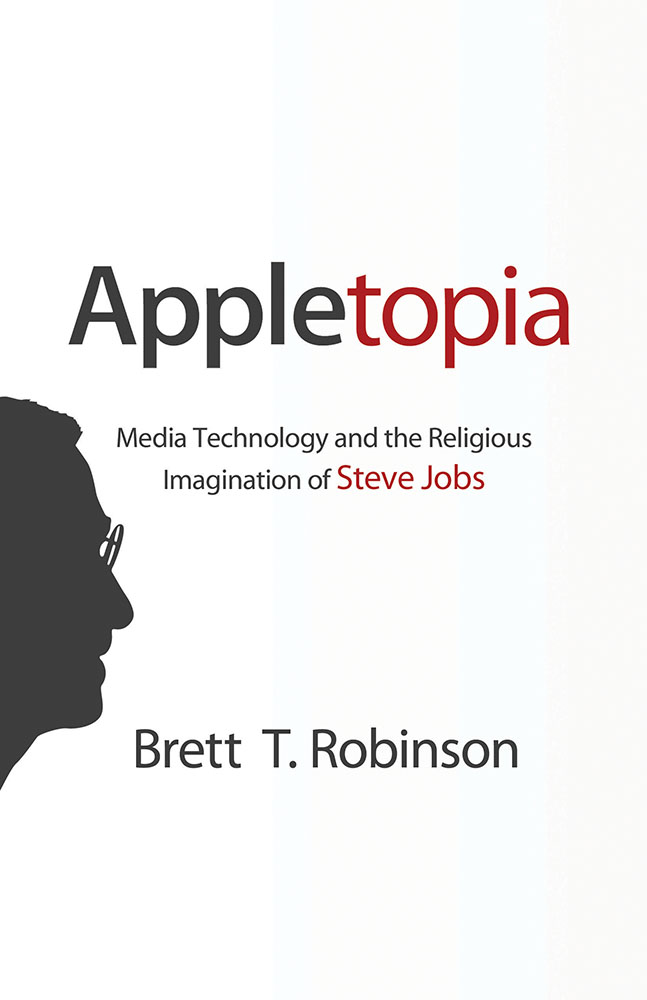

2013 by Baylor University Press

Waco, Texas 76798-7363

All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of Baylor University Press.

Cover design and custom illustration by Jeff Miller, Faceout Studio.

Book design by Diane Smith

eISBN: 978-1-4813-0073-5 (epub)

This E-book was converted from the original source file by a third-party vendor. Readers who encounter any issues with formatting, text, linking, or readability are encouraged to notify the publisher at . Some font characters may not display on older Kindle devices.

To inquire about permission to use selections from this text, please contact Baylor University Press, One Bear Place, #97363, Waco, Texas 76798.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Robinson, Brett T., 1975

Appletopia : media technology and the religious imagination of Steve Jobs / Brett T. Robinson, Baylor University Press.

159 pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-60258-821-9 (hbk. : alk. paper)

1. Social change. 2. Mass mediaTechnological innovationsSocial aspects. 3. Mass mediaInfluence. 4. Jobs, Steve, 19552011. 5. Apple Computer, Inc. I. Title.

HM831.R6293 2013

302.23--dc23

2013002241

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper with a minimum of 30% post-consumer waste recycled content.

To my parents

Thomas E. Robinson

and

Aileen G. Robinson

and to Read Mercer Schuchardt, who started all this

The endless cycle of idea and action,

Endless invention, endless experiment,

Brings knowledge of motion, but not of stillness;

Knowledge of speech, but not of silence;

Knowledge of words, and ignorance of the Word.

T. S. Eliot, The Rock

Now is the hour for us to rise from sleep.

Romans 13:1

Acknowledgments

T he idea that this project could become a book was born over a few Belgian beers on the west end of Pittsburgh. Among the many esteemed writers around the table at the Sharp Edge Creekhouse, I have Mike Aquilina, Craig Maier, Bob Lockwood, and David Scott to thank for cultivating a nascent interest in religion and technology, and Stephen R. Graham for putting me in touch with the fine folks at Baylor University Press.

Carey Newman, director at Baylor University Press, gave me a ten-month master class in writing that will remain with me forever. His use of metaphor to demystify the writing process is legendary and deserves its own book. Baylors team of experts, who read and reread the manuscript and made sure everything on the business end ran smoothly, deserve great thanks and admiration.

The members of my doctoral committee who waded through the early drafts of this project deserve special thanks: Drs. Anandam Kavoori, Carolina Acosta-Alzuru, Janice Hume, Nathaniel Kohn, and Thomas Lessl. Thanks are due also to Dr. Scott Shamp, director of the University of Georgia New Media Institute, who kindled a fledgling fascination with new media. More importantly, Scott introduced me to my wife, which started my lifelong fascination with her.

Saint Vincent College kindly gave me the opportunity to teach a course on the topic of religion, technology, and marketing with an all-star lineup of students who became world-class research assistants: Trish Allan, Eric Arbore, Evan Lucas, Dan Hepple, Nick Mirando, Greta Edgar, Carli Ferretti, and Brendan Kucik.

Thanks also to Marlo Verrilla and Randi Senchur, whose tireless pursuit of interlibrary loan books, images, and citations was nothing short of tenacious.

Thanks to the dozens of Benedictine monks at Saint Vincent Arch-abbey who make the college such a grounded place to work, especially Brother Bruno Heisey, who curated a collection of delightful cartoons for my office door satirizing the sacred cows of technology.

Dr. John Sherry and the University of Notre Dame marketing faculty generously offered vital feedback in the final stages of the project, for which I am most grateful. It was an honor to present this work at my alma mater, where the seeds for these ideas were planted two decades ago.

Thanks to Dr. Michael Krom, a philosopher of the highest rank, who read an early draft of the manuscript and raised excellent questions that vastly improved the final product. Michaels appreciation for the finer things in life coupled with a true contemplative spirit is much needed in a world that has lost ears to hear and eyes to see. His students are very lucky, and I count myself among them.

This book was also the product of helpful conversations with Diane Montagna. Her patient ear, deep insights, and pitch-perfect wordsmithery were indispensable to the project.

Thanks to my immediate family, especially my sister Mandy Pond, my parents Tom and Aileen Robinson, my wifes parents Bruce and Barbara Chaloux, and my late grandparents Bill and Madeline Gilroy and James and Helen Robinson. Your love and support over the years has made all of this possible.

Thanks are due as well to our neighbors David and Robin Klimke, John and Sharon Matz, Boomer and Barb Thompson, John and Sue Bainbridge, and Jerome and Karen Foss for helping with the kids and celebrating all the little things life has to offer. They are all family.

Finally, my deepest thanks belong to my wife and children: thanks to Joseph, my three-year-old assistant, who kept me company in the writing cave during many long afternoons when he could have been playing outside. Thanks to John, my seven-year-old man, whose constant questioning fueled my own. Thanks to Anna, my baby girl, whose smile is nothing short of sublime.

I joked to my wife that writing a book was a little like having a baby: months and months of carrying the ideas around waiting for them to grow, lots of labor trying to get them out, and so on. It was only fitting then that we discovered our fourth child is due the same day this book will be released. Danielle, your generous spirit, your patience, and your grace have been inspirational. Thank you.

Introduction

Media Technology and Cultural Change

I n 2011 by one estimate the most photographed landmark in New York City was not Rockefeller Center or Times Square; it was the Apple Store on Fifth Avenue (see facing page).

In his novel Notre-Dame de Paris, Victor Hugos archdeacon looks up at the Notre-Dame Cathedral with a book in his hand and says, This will kill that. The book will kill the edifice. Hugo explains the archdeacons comment this way:

It was a presentiment that human thought, in changing its form, was about to change its mode of expression; that the

The cultural authority of the cathedral was giving way to the revolution of ideas unleashed by the printing press and books. Hugos parable is instructive for the modern age as well. The authority of the printed page is now giving way to the universality of glass screens.