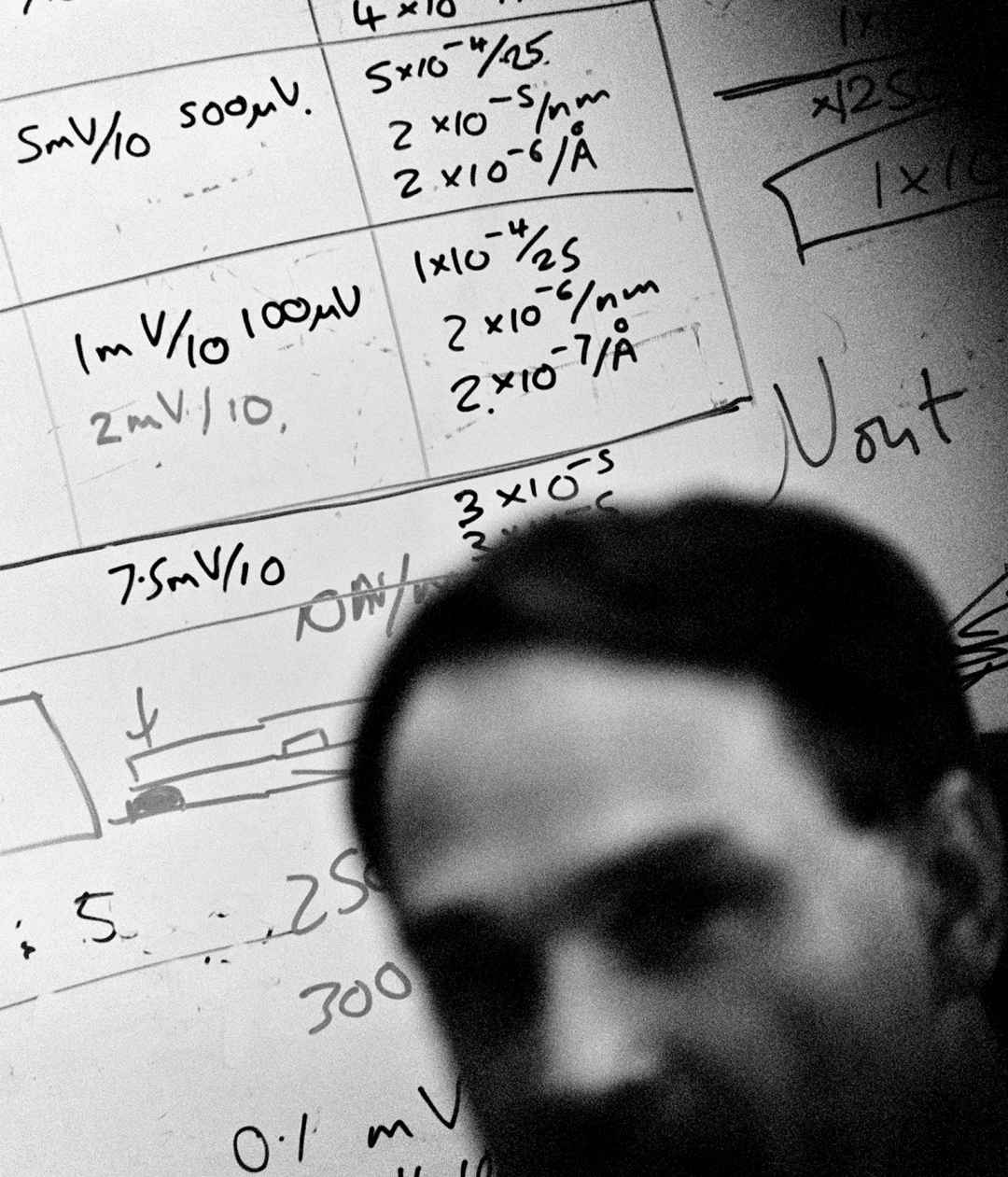

The Mathematical Equations of a Nobel Prize Winner.

Zurich, Switzerland, 1997.

Dr. Gerd Binnig ( foreground ), a 1986 Nobel laureate in Physics, has scribbled notations on a whiteboard describing aspects of his nanotechnology research at IBMs Micro and Nanomechanics Group laboratory. Binnig won the Nobel Prize for Physics with the late Heinrich Rohrer for their invention of the scanning tunneling microscope (STM), a device often described as one of the most significant accomplishments in the history of science. They are considered the fathers of nanotechnology, a field that has given rise to such innovations as highly targeted cancer drugs; AIDS-resistant condoms; 3-D printers that can output toysor human skin; artificial muscles; and self-healing plastic. Despite these seemingly beneficial developments, many have warned of potential threats to humanity raised by this powerful new technology that allows scientists to measure and manipulate atoms.

Thank you for downloading this Atria Books eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Atria Books and Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

Contents

Para Tereza e Paolo, meu amor sempre.

And for those formerly awkward geeks

who now stride like giants

through a technology wonderland

of their own creation.

Behold the new cool kids!

Foreword

by Elliott Erwitt

Photographing the unphotographable has long been the passion and the mission of Doug Menuez. How does one photograph genius? How does one visually communicate the creation and dynamics of world-altering concepts and somehow give insights into the personality of the men and women responsible, the people who essentially just sit and think and in so doing profoundly change our lives?

The answer is, call on Doug Menuez.

Photographs of business meetings and of disheveled people sitting and thinking for hours is hardly sexy visual material. But somehow with his extended time spent in the digital trenches of Silicon Valley and with his diligence applied, not unlike the intensity of his subjects, Mr. Menuez has managed to give us an insight into the minds and processes of these (for the most part) enigmatic people who have and will continue to influence our future more than we can imagine. You only have to consider the short trajectory of fifteen years of amazing technological evolution as chronicled in the pages of Fearless Genius.

In all great affinity groups, one individual raises above all others and we lesser humans are fascinated to know more about him or her. This is true of groups formed around matters religious (Jesus) or martial (Napolon); revolutionary (Tom Paine) or cinematic (Marilyn Monroe); geek (Steve Jobs) or gangster (Al Capone); evangelical (Billy Graham) or political (Abraham Lincoln) or mathematical (Isaac Newton). Steve Jobs, a complicated man, surely belongs among the above group of remarkable individuals. His death long before his time compels us to wonder about his inner person. So we are fortunate indeed to have such insightful and intimate access to Steve Jobs and his peers through the exclusive photographs collected in this book.

Mr. Menuez was there, camera in hand, documenting the fundamental period of the digital phenomenon. He was deeply involved with many of its principal players, making the best possible use of his special access and bearing witness to a place, a time, and a people of extraordinary genius.

Introduction

by Kurt Andersen

Like everyone in Silicon Valley in 1985, Doug Menuez was twenty-eight. During the previous four years IBM had introduced the first PC and Apple had brought out the first Mac, and six years hence the World Wide Web would be born. Like everyone else in Silicon Valley in 1985, Menuez was smart and curious and energetic, with a sense that hed stumbled into exactly the right place at precisely the right time, that the future was being invented by twenty-eight-year-olds staring at screens and pecking at keyboards all over the suburbs south of San Francisco. If he were a poet instead of a poetic photojournalist, he might now be chronicling those giddy days the way William Wordsworth recalled the beginnings of the French Revolution two decades after his idealistic youth in Paris:

Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,

But to be young was very heaven!Oh! times,

In which the meagre, stale, forbidding ways

Of custom, law, and statute, took at once

The attraction of a country in romance!

When Reason seemed the most to assert her rights,

When most intent on making of herself

A prime Enchantressto assist the work,

Which then was going forward in her name!

Menuez, just returned in 1985 from covering Ethiopias drought and civil war, was looking for a new long-term project that wouldnt involve documenting misery and hopelessness. His contemporary Steve Jobs, just purged from the company hed founded, was embarking on a new project that wouldnt involve pleasing shortsighted board members and investors at a mass-market computer company. Jobs agreed to give Menuez total access to his nascent enterprise, NeXT, and Life magazine agreed to underwrite and publish Menuezs portrayal of the making of Jobss new new thing. Day after day, Menuez drove from Marin down to Redwood City to hang, chat, and shoot pictures. By the time the NeXT computer was finally ready to unveil three years later, however, Jobs had, um, you know, sorrychanged his mind. I just decided that Life sucks, he told Menuez. But dont worryyoull have a great time with these pictures someday!

As it turned outas it so often turned outJobss hunch was correct. Because everyone in Silicon Valley knew that Steve Jobs , famously difficult and secretive, had given him free run of NeXT, Menuez now had an imprimatur, which for the next dozen years became a kind of all-access backstage pass to the tech epicenter. In his words, he was a documentary artist with freedom to wander around Adobe at the moment Photoshop was created, as well as Intel, Sun, NetObjects, Kleiner Perkins, and Apple. He was in the singular position of being embedded in units fighting on all the various fronts of the digital revolution. What made his free-range access especially remarkable was the culture of Silicon Valleydespite the superficial pizza-and-foosball looseness, the rival tribes inventing the digital future were manic, competitive, prone to extreme paranoia.

During that seminal decade, they dreamed mainly of bringing a cool new world into being, whatever that might mean, of enabling unprecedented communication and diffusion of knowledge and creative expression. Doug Menuez, the son of a Chicago community organizer, was down with that. Utopianism is in the DNA of the Bay Area and has been from its Gold Rush, fairy-tale modern beginnings through the lush countercultural dreams of lifestyle perfection, all fed by coastal Californias perpetually pleasant weather and ethos of limitless self-reinvention. Of course it was here that the giddy, geeky gearhead tribes took root and flourished at the end of the millennium.

For Northern California baby boomers, even failure could be an opportunity for self-actualization. The heaviness of being successful, Steve Jobs said of his prodigal-son time after being forced out of Apple, was replaced by the lightness of being a beginner again, less sure about everything. It freed me to enter one of the most creative periods of my life.

Next page