Katz Barry M - Make it new : the history of Silicon Valley design

Here you can read online Katz Barry M - Make it new : the history of Silicon Valley design full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: California--Santa Clara Valley (Santa Clara County), year: 2016, publisher: The MIT Press, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Make it new : the history of Silicon Valley design

- Author:

- Publisher:The MIT Press

- Genre:

- Year:2016

- City:California--Santa Clara Valley (Santa Clara County)

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Make it new : the history of Silicon Valley design: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Make it new : the history of Silicon Valley design" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Californias Silicon Valley is home to the greatest concentration of designers in the world: corporate design offices at flagship technology companies and volunteers at nonprofit NGOs; global design consultancies and boutique studios; research laboratories and academic design programs. Together they form the interconnected network that is Silicon Valley. Apple products are famously Designed in California, but, as Barry Katz shows in this first-ever, extensively illustrated history, the role of design in Silicon Valley began decades before Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak dreamed up Apple in a garage.

Offering a thoroughly original view of the subject, Katz tells how design helped transform Silicon Valley into the most powerful engine of innovation in the world. From Hewlett-Packard and Ampex in the 1950s to Google and Facebook today, design has provided the bridge between research and development, art and engineering, technical performance and human behavior. Katz traces the origins of all of the leading consultancies -- including IDEO, frog, and Lunar -- and shows the process by which some of the worlds most influential companies came to place design at the center of their business strategies. At the same time, universities, foundations, and even governments have learned to apply design thinking to their missions. Drawing on unprecedented access to a vast array of primary sources and interviews with nearly every influential design leader -- including Douglas Engelbart, Steve Jobs, and Don Norman -- Katz reveals design to be the missing link in Silicon Valleys ecosystem of innovation.

Make it new : the history of Silicon Valley design — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Make it new : the history of Silicon Valley design" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Cambridge, Massachusetts

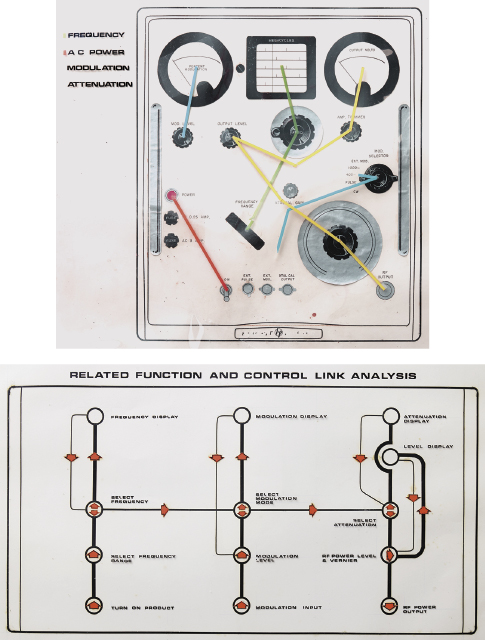

London, England 2015 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Katz, Barry, 1950- Make it new : the history of Silicon Valley design / Barry M. Katz. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-262-02963-6 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Industrial design-California-Santa Clara Valley (Santa Clara County)-History. 2. Industrial design-Social aspects-California-Santa Clara Valley (Santa Clara County)-History. I. Title. ISBN 978-0-262-33093-0 (retail e-book) TS171.4.K38 2015 745.209794'73--dc23 2015009382 This book is respectfully dedicated to the design community of Silicon Valley, past, present, and future, which has given me far more than clean lines and intuitive interfaces. Contents Foreword At a recent MIT event, I had the opportunity to listen to a variety of stories as told by Professor Nicholas Negroponte on how the MIT Media Lab came to be. He shared many great onesranging from his chance dinner encounter with Buckminster Fuller on a cruise ship, to how he came to know William J. Mitchell just when he had arrived in the United States, to his chauffeur-driven adventures with his mentor, MIT president Jerome Wiesner, in launching the Media Lab in the early 1980s.But frankly it was difficult for me to concentrate too closely on what Nicholas was saying, as he had arranged to shorten his presentation so that I might share a few words on the stage with him about my adventures in Silicon Valley. Ive never ceased to be a little nervous around my mentorsespecially when asked to present with them. Then in one of Nicholass stories he shared a name that had recently become familiar to me: Bob Noyce.So I started to pay full attention, as it sounded similar to a name I had recently encountered in my efforts to improve my understanding of the history of Silicon Valley: Robert Noyce.You see, for most of my professional life, I knew the world of technology only through the MIT lens. I am a product of MITs undergraduate and graduate education programs in electrical engineering and computer science. Silicon Valley was way, way, far away for me. The closest I came to Silicon Valley was in my sophomore year when I landed the #2 spot for a summer co-op position at Rolm (I had to Google that name as I realized that I dont hear it anymore). But I ended up at Texas Instruments instead, and went to Dallas every summer thereafter to co-op. My next stop in life was to leave the United States and go to Japan to study design, and I came back to MIT after that.I got to Silicon Valley to visit a few of the Media Labs sponsors there, but I spent most of my time active in the design communities in Europe, Asia, and New York. Now at the age of almost 50, I feel a profound regret that I didnt spend more of my time in Californiain a way, I am trying to make up for it as much as possible by focusing the majority of my energies there.Ive been taught that if you dont know something, you go and learn it. Ive read countless web pages, viewed countless hours of documentary videos, and met countless numbers of people within the Silicon Valley ecosystem. But I know now that if I had read Barry Katzs book Make It New I could have saved myself a ton of time getting to the realization I now have: Design isnt only now getting big in Silicon Valley; it has always been big, but its role had never been well understood. Reading Barrys book renewed my love for Hewlett-Packard, which folks today might think of as just a PC or printer company; back in the day, we MIT nerds knew it as the company that made the best oscilloscopes and calculators. The HP calculators were absolutely worshipped in the eightiesnot just for their functionality, but for their design. Back then, I didnt know the word design . But hearing Barry recount the story of the HP-35, and imagining how liberating it must have felt to free oneself from carrying around a slide rule, it might have well been the iPhone of the day for the geek community.This is what every story in Barrys book comes back to: how each little design-driven innovation by a high-tech company, combined with each birth of a new design agency or consultancy in Silicon Valley, combined with each shift in how a nearby academic institution, like San Jose State (and not just Stanford), contributed one or two key graduates to the ecosystem of innovation there. With each new encounter with an anthropologist, or game designer, or financier, or bold young Brit named Bill Moggridge chancing to open an office far away from his home country just because of an inkling that this computer thing might get really big, what has mattered and endured is the larger picture of the essentiality of each individual person played out over multiple decades.The design ecosystem in Silicon Valley, which has been fostered by a true melting pot of creative disciplines in concert with amazing technologists, is what led to the possibility that Steve Jobs would have been able to give us more than one instance of his one more thingnot just to the cheers of computer-loving scientists and professors, but to hobbyist geeks, to college students, to graphic designers and architects, to businesses of all size, and to grandmoms and granddads and all kinds of people all over the world. The diversity of the ecosystem of Silicon Valley becomes evident through studying its evolution as firsthand journeys by Barry. A visual scan of all the folks he has interviewed, some of them no longer with us, to create this history lays testament to the real importance of this work.Circling back to Robert Noyce, I came across his name in studying the genesis of the venture capital firm where I am currently a partner, Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers. It sits on the mythical Sand Hill Road that Barry refers to in one of his chapters, and it is the venture capital firm to which the younger Larry and Sergey turned to when launching their search engine company now known as Google. In studying the history of KPCB, I came upon the story of the founding of Fairchild Semiconductor and the Traitorous Eightwith Eugene Kleiner among them. I learned by studying its history that the leader of the pack, in Oceans Eleven George Clooney-style, was a charismatic and brilliant technologist named Robert Noyce, who later went on to cofound Intel.Nicholas was sharing his earliest memories of building special graphics technology in the predecessor to the Media Lab, and how they were always starved of memory because it was so expensive and hard to obtain. Luckily, Nicholas had a special angel in the semiconductor industry who was a friend of MIT and who would drop by from time to time, Bob Noyce would come by MIT once a in a while, and unceremoniously hand me a crinkled brown lunch bag filled with memory chips. Much like your uncle might hand you a bag of candy. And it was in that moment, that I felt that sort of zap! of electricity that you feel inside you when multiple worlds collide and connect. I immediately felt my MIT worlds and Silicon Valley connect at the core. Me to Nicholas. Nicholas to Robert Noyce. Robert Noyce to Eugene Kleiner. And Eugene Kleiner, via KPCB, back to me in Silicon Valley.And it was during that same zap! moment that I finally understood Barrys excitement from many months prior when I first arrived to be resident in Silicon Valley. Barry, whom I hadnt met until that evening, had arranged for us to dine at the Stanford Faculty Club to celebrate my joining KPCB as a design partnerthe significance of which was totally lost on me. We spent most of our time sharing stories about our beloved friend in common, the late Bill Moggridge, but Barry would often turn the conversation back to the fact that I had joined a very special venture capital firm in Silicon Valley. I hadnt the slightest idea about the reason for his enthusiasm, but now his wide-eyed excitement makes sense. Barry foresaw a time when design leaders would be invited into all aspects of the Silicon Valley ecosystem of innovation. He knew that the venture capital space was the last domain in which that hadnt occurred, and he was having his own zap! moment that evening.If you have been resident in Silicon Valley during its many heydays, you will love the many stories that Barry tells in this book and feel more than a few zaps; if you were like me, where you were always more than an arms length away from it, you might find your own zap! moment as you see worlds connect inside you as welldirectly connected to people you may recall, or companies youve touched, or even companies you may currently be partnering with.Its obvious that design plays a role in how technology is consumed today, and yet its much less obvious that it has always played such a role. This book has the capability to extend the ecosystem of innovation well beyond the borders of Mountain View, Palo Alto, Menlo Park, Santa Clara, San Jose, and San Francisco. I wish you the same enjoyment that I feel fortunate to have received by studying this rare work of scholarship and friendship. Im truly proud to be associated with this extraordinary book.John Maeda, Design PartnerKleiner Perkins Caufield & ByersMenlo Park, California Acknowledgments I cannot even begin to acknowledge all those who made this book possible: the design community of Silicon Valley, as I have tried to show, is a complex ecosystem within an ecosystem. It includes designers from a dozen disciplines, the engineers and artists who work alongside them, the offices that employ them, the clients who hire them and the people who use, inhabit, and otherwise experience the products they help to create.Although I have verified the accuracy of any quotes attributed to them, in order to avoid conflicts of interest (and sometimes just plain awkwardness) I have resisted the temptation to ask any of the designers discussed in this book to read it in advance of publication. Doing so would doubtless have saved me from errors of fact and judgment, but at the risk of unbalancing the narrative or yielding to a particular point of view. At certain critical junctures, however, I have turned to independent experts to ensure that I have not mangled some technical issue that is beyond my reach (I had a bad experience with FORTRAN when I was fifteen and never looked back): My very deep thanks go to Charles House, John Leslie, Larry Miller, and Charles Irby. The comments and criticisms of these highly accomplished engineers were generously offered and gratefully received, and of course they bear no responsibility for any errors or misjudgments that remain.If I were to multiply the number of designers I have interviewed by the amount of time they have spent with me times their average hourly billing rate, I would have to conclude that the Silicon Valley design community has invested well over $100,000 in this book. I doubt that any of them will ever see a measureable return on their investment, but my greater hope is that they will see themselves accurately reflected in its pages and will gain an appreciation of the historical dimensions of their practice. It is a privilege to thank the following individuals, starting with those who will not have opportunity to evaluate my work:Carl Clement (d. 2011)Douglas Engelbart (d. 2013)Steve Jobs (d. 2011)Matt Kahn (d. 2013)Bill Moggridge (d. 2012)I have interviewed the following individuals, mostly in person but in a few cases I have had to resort to telephone, Skype, or e-mail. They are listed here in the approximate order in which their principal affiliations are represented in the book:Allen Inhelder (Hewlett-Packard)Charles House (Hewlett-Packard)John Leslie (Ampex)Jay McKnight (Ampex)Larry Miller IBM, (Ampex)Peter Hammar (Ampex)Roger Wilder (Ampex)Darrell Staley (Ampex, IDSA)Douglas Tinney (Ampex)Chas Grossman (Ampex, Atari)Jay Wilson (Ampex, GVO)Donald Moore (IBM)Edward Lucey (IBM)Budd Steinhilber (Tepper Steinhilber)Frank Guyre (Lockheed)Dan De Bra (Lockheed; Stanford)Bill English (SRI; Xerox PARC)Philip Green (SRI International)Charles Irby (SRI; Xerox PARC)Jack Kelley (SRI/Herman Miller)Donald Nielson (SRI International)Jeanette Blomberg (Xerox PARC)Stuart Card (Xerox PARC, Stanford)John Ellenby (Xerox PARC; GRiD Systems)Austin Henderson (Xerox PARC)David Liddle (Xerox SDD; Interval Research)Tim Mott (Xerox PARC)Severo Ornstein (Xerox PARC)Jeff Rulifson (Xerox)Abbey Silverstone (Xerox SDD)Robert Taylor (Xerox PARC)Larry Tesler (Xerox PARC; Apple; Amazon)Arnold Wasserman (Xerox; I.D Two)Lucy Suchman (Xerox PARC)Dave Rossetti (Convergent Technology)Karen Toland (Convergent Technology)Nolan Bushnell (Atari)Warren Robinett (Atari)Robert Stein (Atari)Kristina Hooper Woolsey (Atari Research Labs; Apple)Brenda Laurel (Atari Research Labs; Interval Research; CCA)Michael Naimark (Atari Research Labs; Interval Research)Eric Hulteen (Atari Research Labs; Interval Research)Peter Lowe (Ferris-Lowe, Interform, Palo Alto Center for Design)James Ferris (Ferris-Lowe, Apple)Marnie Jones (Stanford; Palo Alto Center for Design; IDSA)Peter Mueller (Interform)John Gard (Steinhilber-Deutsch-Gard; Inova; GVO; IDSA)Steve Albert (GVO)Mike Wise (GVO)Robert Hall (GVO)Michael Barry (GVO)Gary Waymire (GVO)Philip Bourgeois (Studio Red)Regis McKenna (Regis McKenna)Rob Gemmell (Apple)Tom Hughes (Apple)Jony Ive (Appleinterviewed 1998)Susan Kare (Apple)Jerry Manock (Apple)Clement Mok (Apple)Terry Oyama (Apple)Tom Suiter (Apple)Bill Dresselhaus (Apple, Stanford)Hugh Dubberly (Apple; Dubberly Design Office)S. Joy Mountford (Apple; Interval Research)Donald Norman (Apple)Aaron Marcus (AM+A)Abbe Don (Apple; IDEO)Michael Gough (Adobe Design Center)Gary Guthart (Intuitive Surgical)Sal Brogna (Intuitive Surgical)Stacey Chang (Intuitive Surgical; IDEO)Ricardo Salinas (Intuitive Surgical)James Adams (Stanford University)David Beach (Stanford University)Bill Burnett (D2M; Apple; Stanford University)Larry Leifer (Stanford University)Robert McKim (Stanford University)Bernard Roth (Stanford University)Sheri Sheppard (Stanford University)Terry Winograd (Stanford University)Del Coates (San Jose State University)Kathleen Cohen (San Jose State University)Brian Kimura (San Jose State University)John McCluskey (San Jose State University)Robert Milnes (San Jose State University)Pete Ronzani (San Jose State University)Ralf Schubert (San Jose State University)Leslie Speer (California College of the Arts; San Jose State University)Leslie Becker (California College of the Arts)Sue Ciriclio (California College of the Arts)David Meckel (California College of the Arts)Michael Vanderbyl (California College of the Arts; Vanderbyl Design)Colin Burns (Interval Research Corporation; IDEO)Gilliam Crampton-Smith (Interval Research Corporation)Sally Rosenthal (Interval Research Corporation)Doug Solomon (Interval Research Corporation; IDEO)Ellen Tauber Siminoff (Inteval Research Corporation)Rob Tow (Interval Research Corporation)William Verplank (Xerox; Interval Research Corporation; Stanford)Meg Withgott (Interval Research Corporation)David Kelley (Hovey-Kelley; David Kelley Design; IDEO; Stanford)Mike Nuttall (ID Two; Matrix Design; IDEO)Dean Hovey (Hovey-Kelley Design)Tim Brown (ID Two; IDEO)Dennis Boyle (IDEO)Rickson Sun (IDEO)Jim Yurchenco (IDEO)Peter Spreenberg (ID Two; IDEO)Jane Fulton-Suri (ID Two; IDEO)Scott Underwood (IDEO)Paul Bradley (IDEO; frogdesign)Aleksey Novicov (Softbook)Hartmut Esslinger (frogdesign)Herbert Pfeiffer (frogdesign; Montgomery-Pfeiffer))Steve Peart (frogdesign; Vent)Jock Hokanson (frogdesign)Peter Weiss (frogdesign)Jeanette Schwarz (frogdesign)Doreen Lorenzo (frogdesign)Mark Rolston (frogdesign)David Hodge (frogdesign)Dan Harden (frogdesign; Whipsaw)Gadi Amit (frogdesign; New Deal Design)Robert Brunner (GVO; Interform; Lunar; Pentagram: Ammunition)Brett Lovelady (frogdesign; Astro Studios)Yves Bhar (frogdesign; fuseproject)Branko Luki (frogdesign; IDEO; Studio NONOBJECT)Jeff Smith (GVO; Interform; Lunar)Gerard Furbershaw (GVO; Interform; Lunar)Jeff Salazar (Lunar)Ken Wood (Lunar)John Edson (Lunar)Sam Lucente, IBM, Hewlett-PackardJohn Guenther (Design Four; Hewlett-Packard)Astro Teller (Google)Jon Wiley (Google)Isabelle Olsson (Google)Mike Simonian (Google, Mike & Maaike)Bill Wurz (IDEO, Jump!; Google)Kate Aronowitz (Facebook)Paul Adams (Facebook)Soleio Cuervo (Facebook; Dropbox)Aaron Sittig (Facebook)Maria Giudice Hot Studio; Facebook)Christopher Ireland (Cheskin Research; Mix and Stir)Davis Masten (Cheskin Research)Dan Adams (Tesla Motors)Franz von Holzhausen (Tesla Motors)Gregg Zehr (Amazon Lab 126)Fred Bould (Bould Design)Eliot (Seung-Min) Park (Samsung Design America)Jim Newton (Tech Shop)Mark Hatch (Tech Shop)Krista Donaldson (D-Rev)Heather Fleming (Catapult Design)Jocelyn Wyatt (IDEO.org)Valerie Casey (Designers Accord)Additional thanks are due to:Leslie Berlin (Stanford)Kristin Burns (Stanford)Chris Bliss (CCA)Kate Brinks (Nest)Cathy Cook (Facebook)Raschin FatemiRebecca Feind (San Jos State University)Davina Inslee (Vulcan Investments)Kathy Jarvis (Xerox PARC)Chirstopher Katsaros (Google)Bert KeelyLeslie Letts (Amazon)Sarah Lott (Computer History Museum)Henry Lowood (Stanford)Anna Mancini (Hewlett-Packard)Karin MoggridgeAnna Richardson White (Google)Kinley Pearsall (Amazon)Elizabeth SandersDag Spicer (Computer History Museum)Josilin Torrano (Facebook)Richard Saul Wurman (TED)Brandon Warren (IDSA)As noted at several points in the text, I have multiple professional affiliations including some with organizations discussed in this book: California College of the Arts, Stanford University, and IDEO, Inc. Readers will have to judge for themselves whether I have succeeded in my conscientious effort to maintain a balanced and independent point of view. Although I have tried to conduct all of my interviews in a professional manner, it should be noted that I also have innumerable friends, colleagues, and acquaintances at these institutions and throughout the Silicon Valley design community (or I did prior to publication!) and have benefited in profound but un-documentable ways from many years of informal conversation. I offer my thanks to the literally hundreds of additional people who I may have been unable to name, and I extend my apologies to any I may have unwittingly overlooked. Introduction Make it new. Ezra Pound (1934) Rarely does a month go by in which I do not host a delegation of visitors who hope to build a Silicon Valley in Ireland or Poland or Chile or Taiwan. My answer is usually some variant of You cant, and you shouldnt. Silicon Valley is the product of a unique confluence of circumstances that cannot be replicated in time or in space. That is the bad news. The good news is that every region has its own unique set of cultural assets, and the challenge of innovators is to identify them, organize them, and light the fuse.Silicon Valley evolved as a dense network of interconnected parts. Although the famous technology companies may occupy center stage, they operate within a web of interdependencies that also includes venture capital funds that launch them, law offices that protect their intellectual property, trade publications that promote them, and universities that supply their workforces; all of these have received their fair share of attention. Surprisingly, one critical component of the Silicon Valley ecosystem has been overlooked: apart from a few picture books, some celebrity profiles, and ephemeral reviews of the latest gizmos and gadgets, almost no attention has been paid to the role of design. This is an egregious oversight, for designers have played a significant role in transforming the region from a whistle-stop for the San Francisco gentry into the economic engine of the United States. The first objective of this book, then, is to show how design is the missing link in the Silicon Valley ecosystem of innovation.The migration of the computer from the backroom to the desktop was the prime mover, but the Silicon Valley design community was decades in formation, and a second task of this book is to trace it back to its origins and describe the arc of its growth. This returns us to the immediate postWorld War II era, when a small number of electronics firms could be found scattered among the orchards and vineyards that covered the Valley of Hearts Delight. The larger onesHewlett-Packard, Ampex, IBMemployed a handful of designers who labored to package specialized electronic equipment in suitable enclosures. Only in the late 1970s, when companies such as Commodore, Radio Shack, and the fledgling Apple Computer began to direct their attention toward the consumer market, were designers called upon to address the nontechnical user. Most people do not buy printed circuit boards or lithium-ion battery packs or LED panels; they buy tablet computers and automobiles and televisions and a host of other products that have been rendered more-or-less useful and enjoyableby design. This began a profound shift in the very character of the profession that continues unabated: The design teams at Palantir Technologies who are working to make Big Data accessible to intelligence community, or at Coursera to enhance the educational experience of massive open online courses (MOOCs), are working on problems that did not exist a decade ago. As the director of Google[x] explains it, Design unlocks the space and reframes the question.When they first arrived in what would become Silicon Valley, designers waged an ongoing guerilla campaign to gain a hearing from their engineering overlords. Sixty years later the designers at Google and Facebook plead with management to leave them alone so they can get some work done. A third theme, then, concerns their dramatic rise in acceptance: I used to have to persuade clients of the value of design, recalled the CEO of one of the valleys most prominent consultancies, but the battle has been won. It is recognized at the C-level that a design strategy is at the same level of importance to a companys survival as a business plan. It is emblematic of the changed fortunes of design that its leaders are less likely to be seen speaking to the local student chapter of the IDSA than addressing Fortune 100 CEOs at the TED Conference, mingling with heads of state at the World Economic Forum in Davos, or chatting with the First Lady at the White House. Indeed, some observers have dared to speak of the rise of the DEO .The integration of designers into the Silicon Valley ecosystem was anything but a deliberate processto the contrary, as one of my interlocutors noted, I could never get over how ad hoc everything was. If an informed observer had been asked, in the early 1980s, to identify the leading centers of design there would have been an easy consensus: Milan, London, New York, and perhaps Tokyo. Mention of the San Francisco Bay Area would have been met with blank stares. Today there are arguably more design professionals working in Silicon Valley and its Bay Area environs than anywhere else in the world: large consultancies such as IDEO and frog, and one-person studios with names like Monkey Wrench and Shibuleru (Swiss German for calipers); world famous corporate design offices (Apple, Amazon, Adobe); and academic programs to train the next generation of their employees. Whole new fields of design have their origins in Silicon Valley as the profession has responded to the challenges of electronic games, personal computers, interactive multimedia, and hybrid products that may be portable, wearable, or implantable. Making them work has been the historic task of engineering; making them useful is the job of design.It may be helpful to provide a few explanations and qualifications. Although it might be expected that such an endeavor would start with definitions, I have preferred to let both the geography of Silicon Valley and the concept of design emerge from the narrative itself. This decision arises partly from the evolving character of the profession: Over the course of their sixty-year history, designers have been asked to place a VHF signal generator in a sheet metal enclosure and the Like button on the Facebook homepage. They have been strategists and implementers, contractors and consultants, employees and entrepreneurs. Further complicating the picture is the complexity and heterogeneity of the design process itself, which involves a continuum of practices that may operate independently, sequentially, or simultaneously. Its practitioners may have been trained as engineers, in PhD programs in the social sciences, in art schools, or not at all. They may work in corporate laboratories, independent consultancies, boutique studios, or at home, virtually. The attention of the UX (user experience) designer of a Bluetooth headset may be trained on the aspirational lifestyle of the end user, whereas the industrial designer may have an unhealthy fixation on the intertragic notch in the lower concha of her ear. They may despise MBAs, or be MBAs, or both. Some see the professional societies as their advocates, others as their enemies, and for many they are simply sponsors of no-host bars at annual conventions. A definition that embraces them all is unlikely to be of much help.By the same token, Silicon Valley is no longer a meaningful geographic designation, in part because the activities it connotes now extend from Santa Cruz in the south to Skywalker Ranch an hours drive north of the Golden Gate Bridge. Furthermoreas more than a few of my interlocutors have reminded methe history of Silicon Valley does not begin in, nor is it confined to the Bay Area of Northern California: There would be no Xerox PARC without Bolt, Beranek, and Newman in Cambridge, Massachusetts; no Augmentation Research Center without the Washington-based largesse of ARPAs J. C. R. Licklider; no Shockley Semiconductor without Bell Labs in New Jersey; no Atari Research Labs without MITs Architecture Machine Group; we would not be teaching interaction design to graduate students at the California College of the Arts, for that matter, had it not been for the westward migration of the English Arts and Crafts Movement one hundred years ago. At the other end of the historical spectrum, I hope it is obvious that my decision to write about the exceptional story of Silicon Valley does not imply that there are not innovative designers, influential consultancies, successful web-based startups, important technology incubators, and excellent design schools in other regions of the country and the world. There is no ecosystemincluding Silicon Valleys ecosystem of innovationthat does not exist within a larger one.Finally, it should be noted that although objects surely play a part in this story, readers should not expect a design book featuring professionally photographed, museum-ready products. I am at least as concerned with people and practices, ideas and institutions, and I endeavor to trace products upstream to the research laboratories where they may have had their origins and follow them downstream to the clients who will sell them and the customers who will use them. Along the way I do my best to avoid buzzwords like upstream and downstream.Every work of history is as much about what is excluded as what is included, and Make It New is clearly no exception. A history of the Civil War cannot recount every battle, every strategy, every weapon, and every soldiers tale, and the art and craft of the historian is measured by a willingness to make judicious selections, to allow one thing to stand for many things, and to capture broad themes with enough detail to give them substance and, conversely, to give singular facts sufficient context to make them meaningful. I can only hope that stepping back, most readers will find the overall picture to be fair and accurate.Many of my decisions derive from my effort to base this account as fully as possible on original, previously unpublished, primary sources: these include university archives, company records, business and personal correspondence, drawings, prototypes, computer files, and scores of interviews with design leaders from every industry and epoch. Where I have discussed familiar episodesthe development of desktop computing at SRI and Xerox PARC, for instanceI have done so from the unusual perspective of design. Conversely, products such as the insanely great i-flowers that perennially bloom in the enchanted garden of Apple receive comparatively little attention here because they, and their creator, have been so thoroughly covered by the business, the technical, and the popular press. Since I have been privileged with access to a vast array of restricted sources, I have left it to readers interested in the more accessible ones to prowl the Web at will.It is my hope that this book will fill a void that has been strangely neglected, but also serve as a provocation both to historians of Silicon Valley (by demonstrating that design is as important as any of the other factors that have defined the region) and to historians of design (by demonstrating that design today is about much more than form-giving and object-creation). Even more, I hope that it will prove informative and perhaps even inspiring to the community of design professionals whose story it is, and to whom it is respectfully dedicated. The Valley of Hearts Delight In summer 1951, a few weeks after graduating from the University of Washington, Carl Clement found himself in Sacramento, completing a two-week stint in the Army reserves. A friend had just taken an engineering job at Hewlett-Packard, a 250-person instrument company in Santa Clara County, so Clement climbed back into his 1938 Chevrolet and made the three-hour drive to Palo Alto. On a whim, he arranged an interview with Ralph Lee, head of HPs production engineering group. Clement explained that he had just completed a degree in industrial design, to which Lee replied, Whycouldnt cut it as an engineer? He nonetheless offered him a job as a draftsman and arranged for him to be outfitted with a four-legged stool, a drafting table, and a box of pencils. On August 1, 1951, Carl Clement became the first designer to work in what visitors guides still called the Valley of Hearts Delight.Every detail of this charming anecdote carries historical weight: Lee, who had spent the war years at MITs secret Radiation Lab before moving west, shared the prevailing view of industrial design as an artsy form of technical drawing and a refuge for those who couldnt cut it in the test-and-measure world of electrical engineering. Clement, whose studies had been interrupted by three years of wartime service as a radar technician in the Army Signal Corps, envisioned a more challenging future than simply bringing the form and function of consumer products into harmonious alignment. And Santa Clara County, although home to a growing electronics industry and despite the tireless efforts of Frederick Terman, Stanford Universitys famously entrepreneurial engineering dean, was still far better known for its apricot orchards, walnut groves, and verdant fields of lima beans.Hewlett-Packard, in the first postwar decade, supplied instrumentation to the radio and television industries, and Clement set out to prove to his new employer that industrial design could profitably be applied to technical devices and not only to kitchen gadgets and office furniture. It took nearly three years of menial drafting work, but he finally received a bona fide design assignment when he was asked to recommend improvements to the size, color, and graphics on HPs cardboard shipping cartons. It was an important, if inauspicious, start.Clements real interest, however, was the electronic products themselves and not simply the cardboard boxes in which they were shipped. The companys catalog at that time listed an array of test oscillators, waveform analyzers, and vacuum-tube voltmeters, some in wooden cases, most consisting of off-the-shelf components housed in riveted sheet-metal enclosures. Although promotional literature assured customers of the traditional -hp- family characteristics, this referred to technical considerations such as generous overload protection and trouble-free performance rather than any sort of coherent design language. As he learned to streamline his routine drafting tasks, Clement began to spend extra hours in the machine shop tinkering with the housings. These experiments led him to propose a set of concepts intended to improve access to controls and bring some consistency to the HP line.Before long Hewlett-Packards one-man industrial design department had created cabinets and accessories for a dozen of the companys flagship products. In comparison with the utilitarian boxes of the older models, the redesigned instruments are readily identifiable by their rounded aluminum cases, compact vertical configuration (to minimize their footprint on an engineers workbench), and, to emphasize their light weight and portability, a carrying handle. It was a first and conspicuously preliminary effort, but it was well received and Clement was becoming known internally as HPs Raymond Loewya tag he did not particularly appreciate on account of the wide gulf that separated the streamlining of Coca Cola dispensers from the design of signal generators and klystron power supply units.The watershed moment came in 1956, when the company agreed to send him to MIT for a two-week summer course on Creative Engineering and Product Design taught by John Arnold, a lapsed psychologist who had taken a second degree in mechanical engineering. The iconoclastic Arnold had been rattling the conservative MIT engineering establishment with his insistence that what students needed was not more analytical training but a comprehensive approach that would help them overcome blocks to their latent creativity; the same, he argued, could be said for the working professionals who attended his workshops.For many of the 250 industry professionals in the audience that summerengineers and managers from such stolid companies such as General Motors, IBM, DuPont, and GElectures from the likes of cartoonist Al Capp, comprehensivist Buckminster Fuller, and humanistic psychologist Abraham Maslow would have been a hard sell. It probably did not help that they were seated within walking distance of the sites of MITs wartime Rad Lab and Termans Radio Research Laboratory at Harvard, which had applied a rigorously analytical approach to the development of microwave radar and electronic countermeasures with devastating success. To Carl Clement, however, the insight that engineers are trained to define problems in such a way as to imprison their thinking within self-imposed parameters came as an epiphany and he resolved to enlighten his colleagues at Hewlett-Packard. For example, he wrote upon his return to California, suppose we are given the problem of designing a new toaster. The typical starting point is to define the problem so narrowly that the new toaster will likely be little more than the old one with a few cosmetic adjustments. Now on the other hand, suppose we state the problem this way: We are trying to find a way to heat, dehydrate, and brown the surface of bread. This restatement of the problem in basic generic terms opens up all kinds of possibilities. We may well begin by considering the various types of energy which we could useelectrical, mechanical, chemical; perhaps we can add some substance to the bread itself which will produce an exothermic reaction when the bread is sliced, and the newly-exposed surfaces will be self-toasted by exposure to air. Clement concluded his report with an invitation for people to contact him if they might be interested in a course on creative engineering at HP, but there were apparently no takers.This is not to say that his efforts went unappreciated. To the contrary, the industrial design functions at Hewlett-Packard expanded steadily and the staff tripled, first with the hiring of classmate Tom Lauhan from the University of Washington and then Allen Inhelder, the first of a new generation of talent from the Art Center School in Los Angeles. In time, the companys products began to win recognition within the industry for their visual clarity of function, ease and safety of operation, and appropriateness of appearance.In less than a decade, Clement had advanced from being the lone designer in a sea of engineers to supervising an industrial design section of nine young men who showed up at work every morning in white shirts and very skinny black ties. It was, however, a section in name only. The designers did not sit together but were arrayed throughout a large R&D room crammed with electronics workbenches and drafting tables. But within this restrictive domain, Clement was able, finally, to apply the creative engineering strategies he had learned in his summer course at MIT on a larger scale.HPs product line, by 1959, had grown to 373 devices, packed into some sixty-five different shapes and sizes of enclosures, most manufactured both as a nineteen-inch rack-mounted unit and in a narrower bench-top version. At the end of that year, as a cost-saving measure, management instructed the industrial design group to develop a more efficient system for the packaging of its instruments. Many of these devices had been conceived and developed independently, which made it difficult to use them as an ensemble; customers complained that the enclosures impeded access for service and maintenance; the relentless advance of miniaturization had shortened their life spans and rendered many of them obsolete; and the duplication of manufacturing resources required by the rack-mounted and bench-top program made no economic sense.The traditional approach would have been to address the specific points at which an existing apparatus might be improved; indeed, this was precisely the strategy of HPs production engineers, who proposed trimming the bezels and installing hinged trapdoors for easier access.The integrated System I cabinet concept, rackable, stackable, and eminently portable, was introduced in March 1961 at the annual meeting of the Institute of Radio Engineers where, in the unbiased opinion of HPs president, David Packard, it was immediately recognized as the most impressive contribution to the packaging of electronic instrumentation that has ever been made. In fact, both the electronics industry and the industrial design profession shared this favorable assessment. At the Western Electronics Show that summer it received an Award of Excellence for Outstanding Industrial Design; Alcoa selected it in 1962 for its annual Industrial Design Award for outstanding design in aluminum, and the Clement Cabinets were featured at the end of that year in a special four-page supplement in Fortune Magazine .Despite the attention lavished upon them, the population of designers at HP remained small and individual careers loomed disproportionately large. Incidents that may at the time have played out as personal rivalries or office politics can in retrospect be seen as skirmishes in a simmering intergenerational tension. Clement, with a university-based industrial design degree and a strong engineering bent, never learned to draw, whereas his early hires came from arts institutions whose entire curriculum was built around the visual execution of ideas. At Art Center, for instance, they had taken semester-long courses in sketching, drawing, two-point perspective, three-point perspective, rendering, color, surface development, product illustration, layout and presentation, typography, and model construction even before going on to their respective majors in product design, packaging and display, or transpo, and the last six months were spent developing a portfolio. They were typically recent vets with young families to support, were serious about themselves and their work, and carried with them the art school ethos of remaining at the bench all day and all night to finish what they had started. If the tools they needed were not quite right, they simply wandered over to the machine shop and either modified them or fabricated them from scratch. They were also car nuts, aficionados of modern furniture, and they believed that it was necessary not just to do design but also to live design, even on their $450 per month salaries.Clements attention remained focused on gaining acceptance from above, even as his authority was being challenged by a gathering insurgency from below; ultimately, he would be outflanked from both directions. In 1957 Hewlett-Packard, which had been growing steadily and in fact doubled in size in that year alone, reorganized its research and development department into four new product divisions: oscilloscopes, electronic counters, microwave and signal generators, and audio and video equipment. Notably absent was anything remotely approaching an industrial design division, and it had become increasingly clear that design would never be more than an auxiliary service. Clement soldiered on, but with no prospects of a company-wide leadership position, and a loosening grip on the upstart generation he had sired, he announced his resignation effective January 1, 1964. David Packard commended him for work that displayed imagination and innovation while remaining practical and effective, thanked him for his services, and bid him farewell.Carl Clements role in the formation of Silicon Valley design was destined to take one more dramatic turn, but the immediate effect of his departure from Hewlett-Packard was the transition to a management style that more accurately reflected the demands of the products themselves. Believing that the only way to understand an instrument was to embed with the engineers responsible for it, some of HPs younger designers had already defected from a regime they perceived as overly autarkic and autocratic: Andi Ar moved to the oscilloscope division; Jerry Priestly decamped to the computer group; Allen Inhelder lobbied hard to be transferred to the new microwave division, despite a blunt warning from V.P. Bruce Wholey that If you irritate my engineers, youre outta here.In order to gain credibility among the engineers, the designers had to demonstrate that their work had the potential to add measurable value not just to the appearance of a product, but also to its performance. Allen Inhelder, newly embedded in HPs largest and most profitable division, endeavored to do so with the utmost care. Before moving back to California, Inhelder had spent two years working on automotive interiors at Ford, where he added a deep immersion in human factors to the formal skills he had been taught at Art Center: from the automakers engineers he learned that a protruding ignition key can result in a debilitating knee injury in even a minor collision, and from their bible, Woodson and Conovers standard Human Engineering Guide, that the designer must shun style idiosyncrasies and not be led astray by arty concepts which destroy good human engineering practices.The mechanical engineers in the microwave division were favorably disposed to this new, human-centered approach, which promised to go beyond surface styling and ground their physical products in rigorous ergonomic data. The electrical engineers, however, who always formed the elite core of the Hewlett-Packard organization, saw no conceivable relevance of psychology and physiology to their work and were completely uninterested. Inhelders strategic initiative was calculated to win them over by demonstrating that good product design meant more than simply protecting their precious electronics from dust and damage.To support his argument, Inhelder selected the Model 608 VHF signal generator, a product that owed its success to its technical reliability rather than its ease of operation. Through a clever sequence of transparencies overlaid on a rendering of Model 608s control panel, he explained to a gathering of microwave engineers how nearly every aspect of the 1954 interface was arbitrary, inconsistent, and illogical. Because the designers had been summoned after the basic layout had been established, they were able to do little more than simply package the apparatus in a sheet-metal box with holes poked into it to accommodate the already-positioned controls. Had they been part of the product development team from the outset, the process would have begun with a related function analysis to clarify the relation among the instruments constituent assemblies. They would have then clustered the frequency, modulation, and attenuation controls in formally distinct and logically sequenced partitions, each with its own clearly demarcated centerline, and then gone on to specify such details as labeling, color, placement of displays, and selection of knob types. The result would be an instrument whose faceplate was, in effect, a visual schematic of the electronics inside. The e-es were delighted, and by the end of his presentation the microwave division was ready to welcome its first industrial designer.

Next page

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Make it new : the history of Silicon Valley design»

Look at similar books to Make it new : the history of Silicon Valley design. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Make it new : the history of Silicon Valley design and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.