REVOLUTION

in The Valley

REVOLUTION

in The Valley

Andy Hertzfeld

with contributions by Steve Capps, Donn Denman, Bruce Horn, and Susan Kare

OREILLY

Beijing Cambridge Farnham Kln Sebastopol Tokyo

Revolution in The Valley

by Andy Hertzfeld

Copyright 2005 Andy Hertzfeld.

All rights reserved.

Printed in Italy.

Published by OReilly Media, Inc.,

1005 Gravenstein Highway North,

Sebastopol, CA 95472.

OReilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (safari.oreilly.com). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department:

800-998-9938 or .

Editor Allen Noren

Production Editor Philip Dangler

Art Director Michele Wetherbee

Cover Designer Ellie Volckhausen

Interior Designer Melanie Wang

December 2004: First Edition.

Revision History

2004-12-06: First release

2011-09-09: Second release

The OReilly logo is a registered trademark of OReilly Media, Inc. Revolution in The Valley: The Insanely Great Story of How the Mac Was Made and related trade dress are trademarks of OReilly Media, Inc.

Apple, the Apple logo, and all Apple hardware and software brand names are trademarks of Apple Computer, Inc., registered in the United States and other countries.

The song The Times They Are A-Changin by Bob Dylan Copyright 1963; renewed 1991 Special Rider Music. Used by permission.

Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and OReilly Media, Inc. was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in caps or initial caps.

While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the publisher and author assume no responsibility for errors or omissions, or for damages resulting from the use of the information contained herein.

ISBN: 978-1-449-31624-2

[TI]

For my wife, Joyce,

my stepson, Nick,

my best friend, Burrell Smith,

and the rest of the original Macintosh team.

Foreword

There are occasionally short windows in time when incredibly important things get invented that shape the lives of humans for hundreds of years. These events are impossible to anticipate, and the inventors, the participants, are often working not for reasons of money, but for the personal satisfaction of making something great.

The development of the Macintosh computer was one of these events, and it has changed our lives forever. Every computer today is basically a Macintosh, a very different type of computer from those that preceded it. Who were the people who developed this revolutionary computer? What motivated them? What advancements did they make? How were tradeoffs made? What was the environment like where it happened?

The answers to some of these questions can be derived from other books. But they too often have the flavor of highly edited reality TV shows scripted by outsiders who werent there. I occasionally read an article based on good, exhaustive reporting that gets to the heart and soul of this computer and of the people who created it, but none do it as well as this book.

Revolution in The Valley: The Insanely Great Story of How the Mac Was Made is a collection of stories by the actual personalities who gave life to this amazing computer, and its more captivating than any book or article I have read. As youll soon discover, these are people whose passion for doing great things has never before been captured, until now.

Its chilling to recall how this cast of young and inexperienced people who cared more than anything about doing great things created what is perhaps the key technology of our lives. Their own words and images take me back to those rare days when the rules of innovation were guided by internal rewards, and not by money.

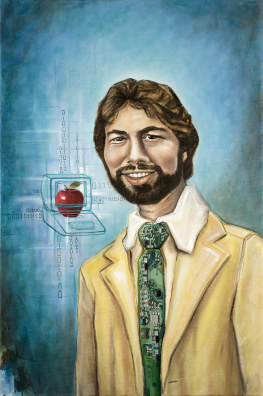

Steve Wozniak

Introduction

The best purchase of my life occurred in January 1978 when I spent $1295 plus tax, most of my life savings at the time, on an Apple II microcomputer (serial number 1703) with 16K bytes of RAM. I was instantly delighted with it, and the deeper I dug into it, the more excited I became. It had incredible features, such as seven expansion slots and high-resolution color graphics. But it also had an ineffable quality that went beyond mere features. Not only could I finally afford to have my own computer, but the one I got turned out to be magic; it was better than I ever thought it could be.

I started spending most of my free time with my Apple, and then most of my not-so-free time, exploring various technical aspects of the system. As I taught myself 6502 assembly language from the monitor listing that came with the machine, it became clear to me this was no ordinary product: the coding style was crazy, whimsical, and outrageous, just like every other part of the designespecially the hi-res color graphic screen. It was clearly the work of a passionate artist. Eventually, I became so obsessed with the Apple II that I had to go to work at the place that created it. I abandoned graduate school and started work as a systems programmer at Apple in August 1979.

Even though the Apple II was overflowing with both technical and marketing genius, the best thing about it was the spirit of its creation. It was not conceived or designed as a commercial product in the usual sense. Apple cofounder Steve Wozniak was just trying to make a great computer for himself and impress his friends at the Homebrew Computer Club. His design somehow projected an audacious sense of infinite horizons, as if the Apple II could do anything, if you were just clever enough.

Most of the early Apple employees were their own ideal customers. The Apple II was simultaneously a work of art and the fulfillment of a dream, shared by Apples employees and customers. Its unique spirit was picked up and echoed back by third-party developers, who sprung out of nowhere with innovative applications.

Making the transition from an ardent Apple II hobbyist to an Apple employee was like ascending Mount Olympus, walking among the gods, working alongside my heroes. The early team at Apple was full of amazing individuals, people like Steve Wozniak, Rod Holt, and Mike Markkula. It was a privilege to get to know them and learn the company mythology firsthand.

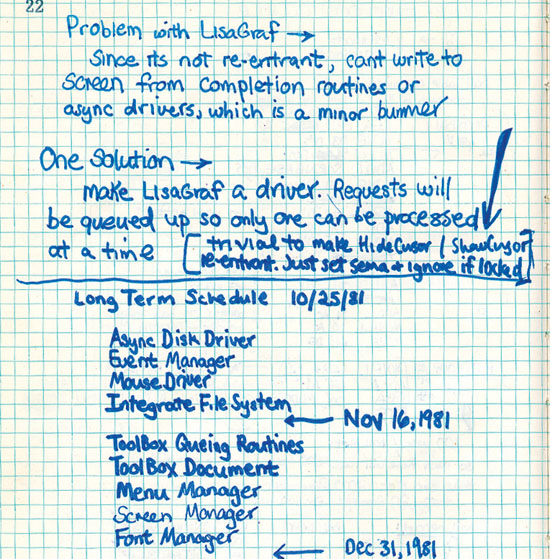

Apples other co-founder, Steve Jobs, had no shortage of vision or ambition. Flush with the rapidly growing success of the Apple II, Apple initiated two new projects in the fall of 1978 (codenamed Sara and Lisa), which were aimed beyond the hobbyist market. Sara was a souped-up successor to the Apple II, using the same microprocessor with an 80-column display and additional memory, intended for small businesses. Lisa was an ambitious, more expensive, easy-to-use, next generation office computer featuring a revolutionary graphical user interface (GUI). By the time I started at Apple in August 1979, both projects were staffed up and well underway.