The Apple II Age

The Apple II Age

How the Computer Became Personal

Laine Nooney

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2023 by Laine Nooney

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2023

Printed in the United States of America

32 31 30 29 28 27 26 25 24 23 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-81652-4 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-81653-1 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226816531.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Nooney, Laine, author.

Title: The Apple II age : how the computer became personal / Laine Nooney.

Description: Chicago : The University of Chicago Press, 2023. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022045947 | ISBN 9780226816524 (cloth) | ISBN 9780226816531 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Apple II (Computer) | Microcomputers.

Classification: LCC QA76.8.A66 N66 2023 | DDC 005.265dc23/eng/20221021

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022045947

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

In memory of Margot Comstock, the founder of Softalk.

19402022.

Her passion for the Apple II left behind the trace that made this book possible.

Contents

Every once in a while, Steve Jobs announced, a revolutionary product comes along that changes everything.

It was the morning of January 9, 2007, at the annual MacWorld convention in San Francisco, and Jobs, Apple Computers CEO and visionary in chief, was angling to make history. Attendees from across the creative sectors had camped outside the Moscone West convention center since nine oclock the night before, had endured Coldplay and Gnarls Barkley as they stabled inside the auditorium awaiting Jobss arrival, had dutifully, even passionately, cheered for Jobss rundown of iPod Shuffle developments and iTunes sales, along with a pitch for Apple TV packed with clips from Zoolander and Heroes. And as everyone suspected, it all turned out to be one long tease for the only thing anyone remembers. Steve Jobs was unveiling the iPhone.

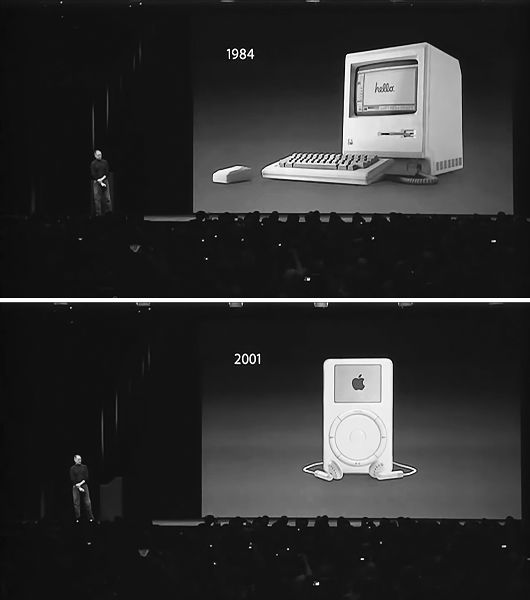

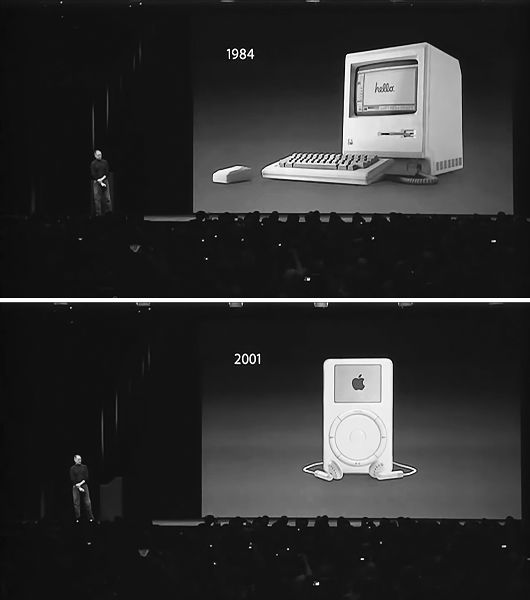

Pitched by Jobs as the convergence of three distinct technological traditionsthe telephone, the portable music player, and internet communication devicesthe iPhone needed a conceptual on-ramp to help people frame its revolutionary potential. So Jobs opened with a little Apple history. Behind him on stage, a slide deck transitioned to a picture of the iconic 1984 Macintosh computer, followed by the 2001 iPod. The selections were deliberate: both had shifted Western norms about how computer technology fit into our lives, changed our gestures, altered our workflows. In Jobss foreshortened timeline, the iPhone was the natural inheritor of this trajectory of innovation, a capstone technology in a chain of hardware evolution straddling the end of one century and the beginning of another. The iPhone promised to braid Apples many trajectories into a single impulse: by drawing a direct path of influence from the Macintoshs graphical user interface to the dial of the iPod to the touchscreen of the iPhone, Jobs presented the development of all three as natural and inevitable, subtly suggesting a metaphysical inheritance between them that transcends their status as mere products. This is company history told only through its virtues, a techno-secular Creation of Adam in which the first man reaches out with a mouse and God swipes back with a finger.

But here we should pause, and consider all the history that must be put aside for Jobss version of events to hold together. Elided by necessity are all the Apple products that flopped or failed, the ideas that stayed on the drawing board, the incremental alterations intended to get Apple through its next quarter rather than catalyze a revolution. Think of the clamshell laptops, the Lisa workstations, the QuickTakes, Newtons, and Pippins. But there is one absence in particular that reveals more than the rest: the Apple II. (See pl. 1.) Released in 1977, seven years before the Macintosh, the Apple II would become one of the most iconic personal computing systems in the United States, defining the cutting edge of what one could do with a computer of ones own.

Like the founding of Apple Computer Company in 1976, the development of the Apple II is often presented as a collaboration between Steve Jobs and his lesser-known partner, Steve Wozniak. In truth, the product was almost entirely a feat of Wozniaks prodigious talent in electrical engineeringthough it likely would never have come to market with the bang that it did had Jobs not been rapaciously dedicated to commercializing Wozniaks talents. It was the Apple II, not the Macintosh, that made Apple Computer Company one of the most successful businesses of the early personal computing era, giving the corporation a foundation from which it would leverage its remarkable longevity. Yet the system cannot appear in Jobss harried, abridged history. The Apple II renders too complicated the very mythology he was trying to enact through stagecraft.

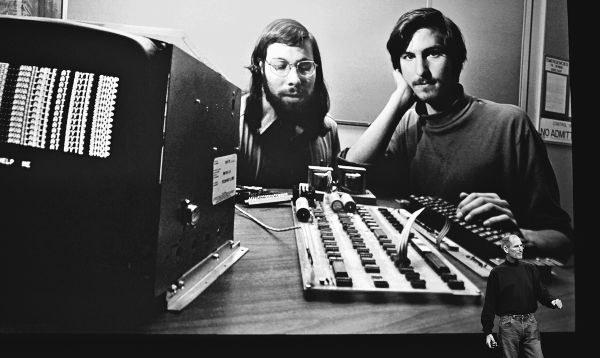

Scenes from the introduction of Steve Jobss 2007 iPhone keynote, highlighting Apples history of technological innovation with the Macintosh and the iPod. Screen captures by author. Video posted on YouTube by user Protectstar Inc., May 16, 2013: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VQKMoT-6XSg.

To attend to such absences in Jobss speech, to its false starts and the things left out, is to make the case for a history of computing that is more intricate than our everyday blend of hype and nostalgia. For many readers, the history of personal computing is personal. It is something witnessed but also felt, a nostalgic identification with a technological past that lives within. It comes alive at surprising moments: a familiar computer in the background of a television show, a YouTube video recording of the AOL dial-up sound, a 3.5-inch floppy disk found in a box of old files. These intimate memories of simpler technological times routinely form the ground from which personal computing circulates as a historical novelty. And beyond our individual reminiscences, personal computings past is continually leveraged by those invested in using the past, like Jobs did, to barter for a particular kind of future.

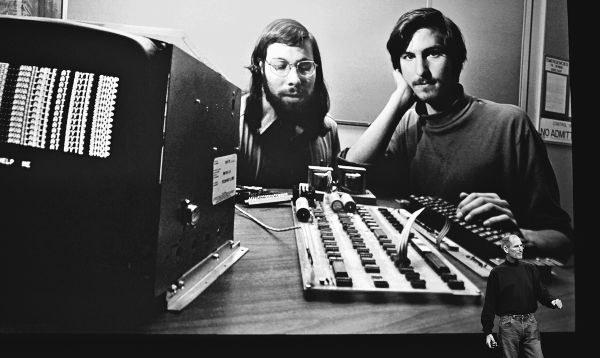

Steve Jobs stands dwarfed by his own history, speaking before a 1976 photo of himself and Apple cofounder, Steve Wozniak. In the historical image, Wozniak and Jobs pose with Apple Computers first product, the Apple 1 microcomputer. Photograph of Jobs taken at the Apple iPad tablet launch, held at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts Theater in San Francisco, California, January 27, 2010. Photograph by Tony Avelar, image courtesy Bloomberg via Getty Images.

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).