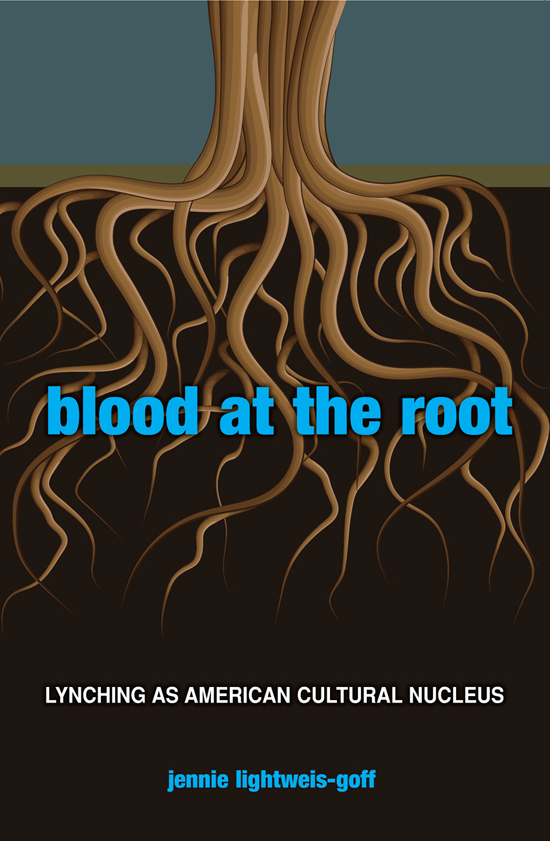

An earlier version of the Introduction appeared as Blood at the Root: Lynching, Memory, and Freudian Group Psychology in Journal for Psychoanalysis of Culture and Society 12, no. 3 (September 2007): 28895.

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2011 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Production by Kelli W. LeRoux

Marketing by Anne M. Valentine

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lightweis-Goff, Jennie.

Blood at the root : lynching as American cultural nucleus / Jennie Lightweis-Goff.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4384-3629-6 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4384-3628-9 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. LynchingUnited StatesHistory. 2. United StatesRace relations. 3. Race relations in literature. I. Title.

HV6457.L54 2011

364.1'34dc22 2010032064

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Love, Debt, Collaboration, and Thanks

In May 2003, Andy Doolenthen an assistant professor at Clemson Universitylent me his copy of Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America. At the time, I was writing Reconstructing Hitler's Body in Cinema, an examination of the relationship between Axis propaganda and the heroic comedies of the Allied countries, a study subsequently submitted as a thesis for the Masters of Arts at Clemson University. After three months of reading, researching, screening, writing, and arguing about Leni Riefenstahl's Triumph des Willens, I was astonished at the distinction between the modes of propaganda I knew and the one with which Doolen had forced an encounter. In the length of Riefenstahl's film, neither Hitler nor his lieutenants use the word Jew, and words like race and religion are studiously avoided, though blood is mentioned once. Gazing at Laura Nelson's raped and mutilated corpse, Leo Frank's slashed throat, and Jesse Washington's charred flesh made it impossible for me to look across an ocean for modes of racist propaganda, when citizens of my own nation had created forms of propaganda that placed neither racism's violence nor virulence under erasure, but displayed both as proudly as its politicians wave its flag. I dedicated myself to the completion of Blood at the Root: Lynching as American Cultural Nucleus on that day in 2003. Though I have lived with this violence, I acknowledge, like James Allen, the curator of Without Sanctuary, that it has given me purpose and, in the pursuit of that purpose, a hunger that will not be sated until justice rolls down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream (Amos 5:24).

I must thank a remarkable group of scholars at the institutions at which I have made my homes, most especially Jeffrey Tucker, Stephanie Li, David Bleich, Joan Saab, Greta Niu, and Genevieve Guenther at the University of Rochester, as well as Catherine Paul, Martin Jacobi, and Beth Daniell at Clemson, and Greg Forter, Ed Madden, and Pamela Barnett at University of South Carolina. Two professors at ClemsonLee Morrissey and the late Fred Shilstonetrained me as a stylist, relieving me of the misguided sense that academic writing ought to be sapped of rhetorical beauty. I am grateful to both, and wish that I could thank Fred once again. The faculty and staff of the Susan B. Anthony Institute for Gender and Women's Studies at University of RochesterProfessors Jeffrey Runner and Honey Meconi, as well as administrators Aimee Senise Bohn and Angela Clark-Taylorhave made the writing of this project much more comfortable than it would have been without them. At the University of Rochester, I learned much from my peersparticularly Russell Sbriglia, Kristi Castleberry, Jessie Crabill, and Rachel Leewho have been patient, kind, and attentive readers of this project and loving readers of this strange animal. All of them are very dear to me.

Hobart and William Smith Colleges, which hired me the morning of my dissertation defense, were willing to take a risk on a scholar and teacher who had already shown herself to be the bastard child of her discipline of study. Little did I know that my illegitimacy would prove a boon in an institutional setting where interdisciplinarity is a given, rather than a goal to be striven for. Though I was hired to teach Women's Studies, I feel almost as though I discovered feminism under the tutelage of the women I met there: my students as well as the tenured women I began to think of (lovingly) as the Coven. Betty Bayer and Susanne McNally were patient and remarkable guides in the first year of my academic career; anyone would be lucky to experience the intellectual vitality and power that I observed in their presence. Surrounded by Susan Henking's books in our shared office, I attained my second education in both feminism and psychoanalysis; I am grateful that she trusted me with the knowledge. Anna Creadick offered comfort and kindness more than once.

I would be remiss not to thank a number of students who have inspired me. In no particular order: Libby Greene, Patricia Bamonti, Gina Ragusa, Molly DiStefano, David Weisberg, Kyle Roe, Jess McCue, Jamie Frank, Amanda Fleming, Kyvaughn Henry, Julia O'Halloran, Mr. President J. David Schlink, Julianne Nigro, Catherine Yee, George-Tom Rogers (who has nothing to lose but his chains), Joshua Reynolds, Ellie Adair, Leah Swenson, Angela Stoutenburgh, Erin Cunningham, Erin Laskey, Anna Grushevksy, David Benavidez, Michela Paniccia, Susan Storey, Glenn Buchberger, John Kowalcyzk, Heather O'Riordan, Campbell Garland, and Roger Arnold. This list concludes with Roger's name because he is a Hobart man for all seasons, and a gift to me as a teacher and an author. I am grateful for his attentive reading of this manuscript in his senior semester, when he was writing his own thesis. One day, I will return the favor with his first book.

On the day that my first year of graduate school ended, I packed a bag, rushed to the side of my then-boyfriend, Chip, and spent a year off the grid, but not without connection. In our house in Central, South Carolina, painted with stars and sunflowers, with a fine mat of moss on the shingled roof, I met Keith Wayne Davis, Bethany Purdin, and Mark Theiling. Flung to the far corners of a continent though we may be, I love them. They move my heart, I assure them, every damn time. In New York, I am reminded of Mark in the company of his brother Dale, who lives, mercifully, much closer. Holly Norton can argue circles around me, and I am grateful when she does. During our years in Western New York, Dale and Holly have often given Chip and me access to nature at their farm in Skaneateles. The waterfall, the fields, and the chickens were always precisely what we needed.