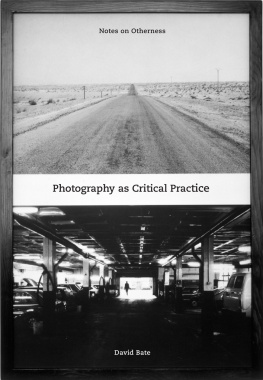

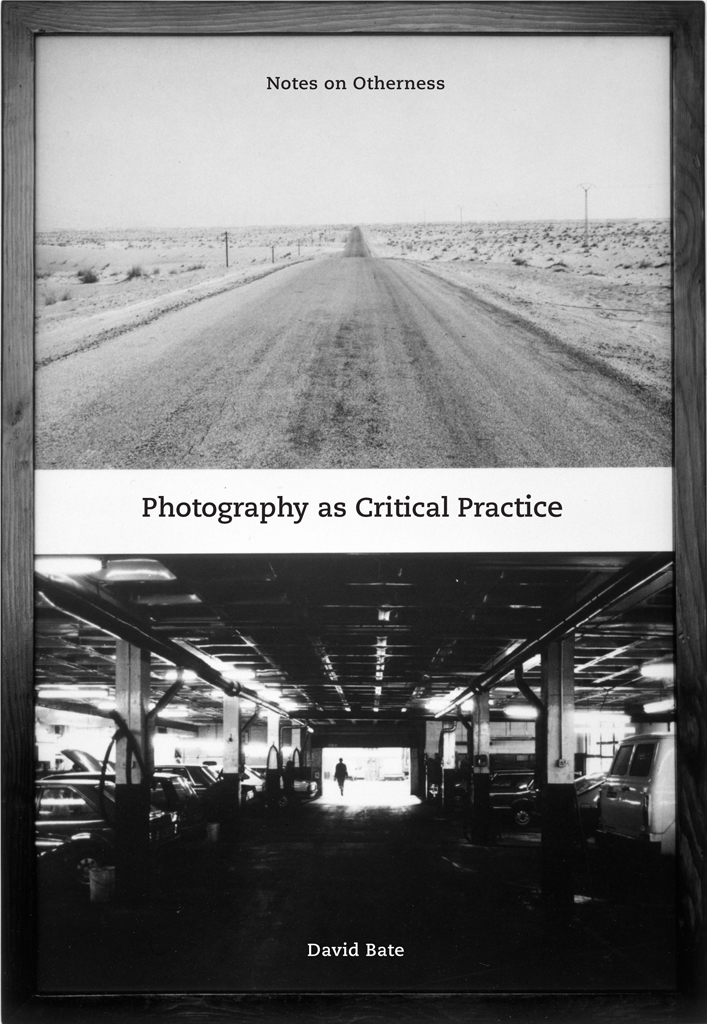

Photography as Critical Practice

First published in the UK in 2020 by Intellect Books, The Mill, Parnall Road, Fishponds, Bristol, BS16 3JG, UK

First published in the USA in 2020 by Intellect Books,

The University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th Street, Chicago, IL 60637, USA

Copyright 2020 Intellect Ltd

Production Manager: Emma Berrill

Copy-Editing: MPS Technologies

Cover Image: David Bate, from Perfect Harmony

Cover Design and Layout Design: Holly Rose

Typesetting: Holly Rose

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written consent.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-78938-198-6

ePDF ISBN: 978-1-78938-200-6

ePub ISBN: 978-1-78938-199-3

Printed and bound by

Severn, UK

Photography as Critical Practice

Notes on Otherness

Contents

Alfredo Cramerotti

Elna Ruka

Katrin Kivimaa

Parveen Adams

Liz Wells

Alfredo Cramerotti

Form Leading Practice

While reading around on literatures on the idea of form in order to write this foreword, I came across Plato.1 According to the philosopher, and contrary to what one may think, form is not the exemplification or a delineation of an object, but its very essence. That is to say, without form, a thing would not be the kind of thing it is or what we assume it to be.

This presents form as a sort of idealization of an object, more than a description or a feature of it. It seems to indicate that, in order to achieve a goal, we need first to imagine a form for it, and then proceed following a set of visual instructions. This, in turn, reminds me of the teaching of the theatre director and playwright, Jerzy Grotowski. For him, one needs to have a rigorous internal structure to be able to shape cultural forms with the force of life.2 Conversely, it is necessary to have a strong pressure in life to be able to respond with the greatest of the discipline of forms. This suggests that, the more intense a life is the denser both on psychological and material level the more form is important as an instrument of the thinking process, and as a tool for physically shaping outcome.

It follows that the kind and variety of forms we seek, employ, and generate in our daily occupations be these aesthetical, operational, or ethical function not as outcomes of the cause/effect duality of thought and action, but as the very quintessence of the discerning process itself necessary before even setting off for what we want to achieve. In short, employing a certain discipline of forms becomes the generative and organizing principle for human culture. Moreover, it epitomizes a method of accountability to our living environment.

Notes

See Russell Dancy, Platos Introduction of Forms (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004); William David Ross, Platos Theory of Ideas (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1951); and Clyde Pharr, rev. by John Wright, Homeric Greek: A Book for Beginners (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1985).

See Gabriele Vacis, Awareness: Dieci giorni con Jerzy Grotowski (Milan: Rizzoli, 2002).

Acknowledgements

It would be difficult to find all the many individuals who were involved in commissioning some of the projects and writings published here, some are from over two or more decades. Needless to say, there have been many valuable contributions and help given over such a long period from friends, colleagues, curators, editors, and other people occupying roles related to these (none of these roles listed are mutually exclusive). I heartily thank them all. I would like to particularly thank some longstanding friends and acquaintances who all helped in ways they may not have even realized, whether directly or indirectly: Danielle Arnaud, Gloria Chalmers, Andy Darley, Michael and Fred Dyer, David Evans (who sadly passed away in 2018), Patricia and Marie-France Martin, Peter Hall, Eve Kiiler, Susan Morris, Piia Ruber, and many others, who all know who they are.

In addition, I would also like to thank those who specifically helped in one way or another with the preparation of this book: Alfredo Cramerotti for initiating the book, Emma Berrill in production, Paula Gortzar for valuable help with retrieving texts, Joanna Burejza for image scanning, Karin Bareman for manuscript assistance, and Parveen Adams, Katrin Kivimaa, and Liz Wells for their written texts and Elna Ruka for her permission to use the annotated interview here.

This book draws together a number of my photographic works and essays, and places them chronologically alongside each other for the first time in one volume. Selected from the production of more than three decades of visual work and writing, the central focus is on a relation between photography and critical practice. Whether in the form of visual photoworks or written essays, and whether displayed in galleries and museums or disseminated in magazines, journals, and catalogues, the overall focus of the works selected here is the idea of a critical practice. Why critical practice?

Photography plays a key role in the everyday social production and reproduction of subjectivity. As producers or consumers of photographic images (a distinction barely discernible in everyday twenty-first-century life), our identities and subjectivities are enmeshed in these technologies of representation, with their effects and affects, their intentions and meanings. Actively and passively the term critical practice links this productive role of photography to an interrogative function. To speak of a critical practice is to invoke a conception of practice that does not sink into the vague preconceived ideas of creativity (creative practice as simply a form of personal expression) or the specific heroic commitment to grand historical events implied by the term political art. The visual works and writings here aimed to mix up these conventional modes of practice and commitment in a myriad of different ways.

In other words, to speak of a critical practice does not mean the exclusion of the imaginary or the political, but to reconfigure them in ways that do not conform to the recognizable doxa and conventions of either format. To this extent I associate the term critical practice with a disjunctive form, one that can include creative and political or ideological questions as part elements of the work. We might otherwise, directly or indirectly call this work experimental, that is, if that term did not come with its own existing counter-intuitive baggage. The orientation of the critical practice in these projects and writings has been towards what I am calling otherness, as a form of alienation of identity. The photoworks and essays address, explore or consider, in varied ways, different territories or aspects of otherness.

Notes on otherness

Just as photographic images are implicated in the construction of human subjectivity, so they are also involved in the construction of forms of otherness. Otherness is a multi-discursive concept, a term known and used in different fields of knowledge and everyday experience. The Other is something I do not know, even the mOther who cared for us. Every construction of an I is also the implicit formation of an other at the same time. In this sense, literally speaking, the term other is completely open; it cannot be reified into one object or discourse of negation. Just as the works in this book are also intended to be open as