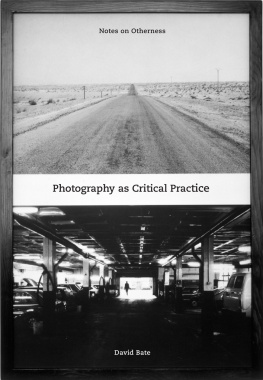

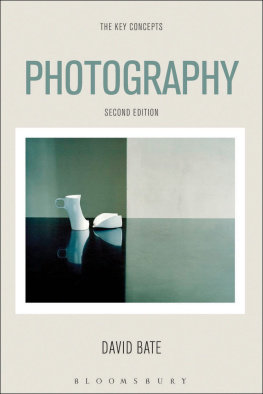

PHOTOGRAPHY

ISSN 1747-6550

The series aims to cover the core disciplines and the key cross-disciplinary ideas across the Humanities and Social Sciences. Each book isolates the key concepts to map out the theoretical terrain across a specific subject or idea. Designed specifically for student readers, each book in the series includes boxed case material, summary chapter bullet points, annotated guides to further reading and questions for essays and class discussion.

Film: The Key Concepts Nitzan Ben-Shaul

Globalization: The Key Concepts Thomas Hylland Eriksen

Food: The Key Concepts Warren Belasco

Technoculture: The Key Concepts Debra Benita Shaw

The Body: The Key Concepts Lisa Blackman

New Media: The Key Concepts Nicholas Gane and David Beer

PHOTOGRAPHY

The Key Concepts

David Bate

English edition First published in 2009 by Berg Editorial offices:

First Floor, Angel Court, 81 St Clements Street, Oxford OX4 1AW, UK 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA

David Bate 2009

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the written permission of Berg.

Berg is the imprint of Oxford International Publishers Ltd.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bate, David, 1956-

Photography : the key concepts / David Bate.

p. cm. (The key concepts, ISSN 1747-6550)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-1-84520-667-3 (pbk.)

ISBN-10: 1-84520-667-3 (pbk.)

ISBN-13: 978-1-84520-666-6 (cloth)

ISBN-10: 1-84520-666-5 (cloth)

1. Photography. I. Title.

TR146.B337 2009 770dc22

2009015038

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84520 666 6 (Cloth)

978 1 84520 667 3 (Paper)

Typeset by JS Typesetting Ltd, Porthcawl, Mid Glamorgan Printed in the UK by the MPG Books Group

www.bergpublishers.com

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Marcus Bohr and Layal Ftouni for their help with picture research. I would also like to thank Rosie Thomas and Andy Golding at the University of Westminster for their support and research time and Tristan Palmer, the series editor at Berg.

INTRODUCTION

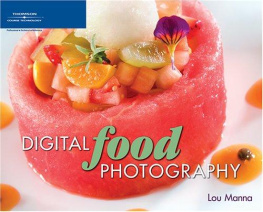

When you buy a camera it normally comes with a handbook that tells you how to use it. With digital cameras this is now even incorporated into the computer chip as preconfigured scene modes. A digital camera I own has preset landscape, portrait, night scenes, food, party and other modes. These instructions in manuals and scene settings usually include tips on how to take better pictures. What these examples give us are not only the rules for how to take better photographs in certain situations, but also an introduction to the typical conventions of photography. The more inquisitive might ask why those conventions are so common and so often repeated within the history of photography.

While this book is in no way an instruction manual, it does aim to provide an introduction to the activity of photography. It is a guide to key concepts in photography. It seeks to introduce the operating conventions of a number of photographic practices, not necessarily so as to make better photographs, but to understand their operations within a more critical framework. Thus it aims to provide an introduction for those wishing to study photography and who are interested in it as a practice and its critical effects. Since photography is employed in so many different aspects of life, across a whole range of cultural and social uses, the scope of such a study is extremely large.

There are many ways in which photography might be introduced. For example, a study of photography could be conducted through investigating the key institutions that use it: advertising, journalism and news, amateur and tourist photography, fashion, art and documentary, police and military or even uses on the www. The sociological anatomy of these institutions might reveal the systems by which photographs are produced, the arteries of power and decision-making, or even the creative space that photographers are supposed to occupy. Such a project is probably urgently needed, but not for my purposes here. It would tell us about the functions of those institutions and only their uses of photography.

Yet the same categories of photograph are also found in other institutional uses of photography. For example, the police may use a specific type of portraiture in a mugshot. This picture may then be shown in a newspaper or in some cases on billboards, thus appearing across at least three institutional settings: the police, newspapers and the sphere of advertising, each with their own specific conditions of spectatorship, discourse and values. Other types of photograph have even more discursive lives.

Photographs are, as almost everyone knows, part of everyday life for many people all over the world. If I wish to travel, a photograph of my face is required to indicate my identity in my passport, without which it would be hard to go anywhere. I am likely to have already seen photographic images of my destination before I have even been there. Tourism, for instance, is a massive, billion-dollar global industry that uses multiple genres of photography to advertise its products: holiday locations. It uses landscape conventions to sell the location, portraiture to represent the types of people who live there (or who you should meet there), while still life is used to show the culture you can see there: food, drinks, tax-free goods, local produce, souvenirs, etc.

Camera companies make assumptions about what a good picture is, based on the widely held popular view and established conventions of photography: portraits, landscapes, close-ups or still life, event pictures such as sports or holidays. The endurance of these types of pictures, their very repetition, is astounding. By focussing on the characteristics of such genres of photography we might see why these types of images have such value and traffic across so many different institutional practices. So I have elected to choose categories for chapters that lend themselves to a diversity of applications.

The first two chapters consider the key concepts of history and theory respectively, as they relate to the general study of photography. History has been a dominant approach towards photography, although it has often fallen short in accounting for the differences between photographs. Even so, the relation between history and photography is twofold. On the one hand photographs have made their own impact on history, by providing images of places, spaces, faces, events and things that have existed in the past. Although not to be taken simply at face value, such images provide a new type of historical artefact. The second issue is how or what historical account we give of photography itself, which is a real challenge given the increasingly vast numbers of photographs.

Theory has been the province of different conceptions of its object: photography. This now includes thinking about what we do with it: ideology. The chapter on theory here considers different phases of thinking on photography and indicates some of the limits and possibilities offered by them.

With the exception of the final chapter, which considers the increasingly important topic of the global impact of photography, the other chapters deal with photography in terms of genre. As a category, genre probably requires some sort of explanation, if not justification, since its inclusion as a key concept of photography is probably something of a novelty.

Next page