Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the Print Version

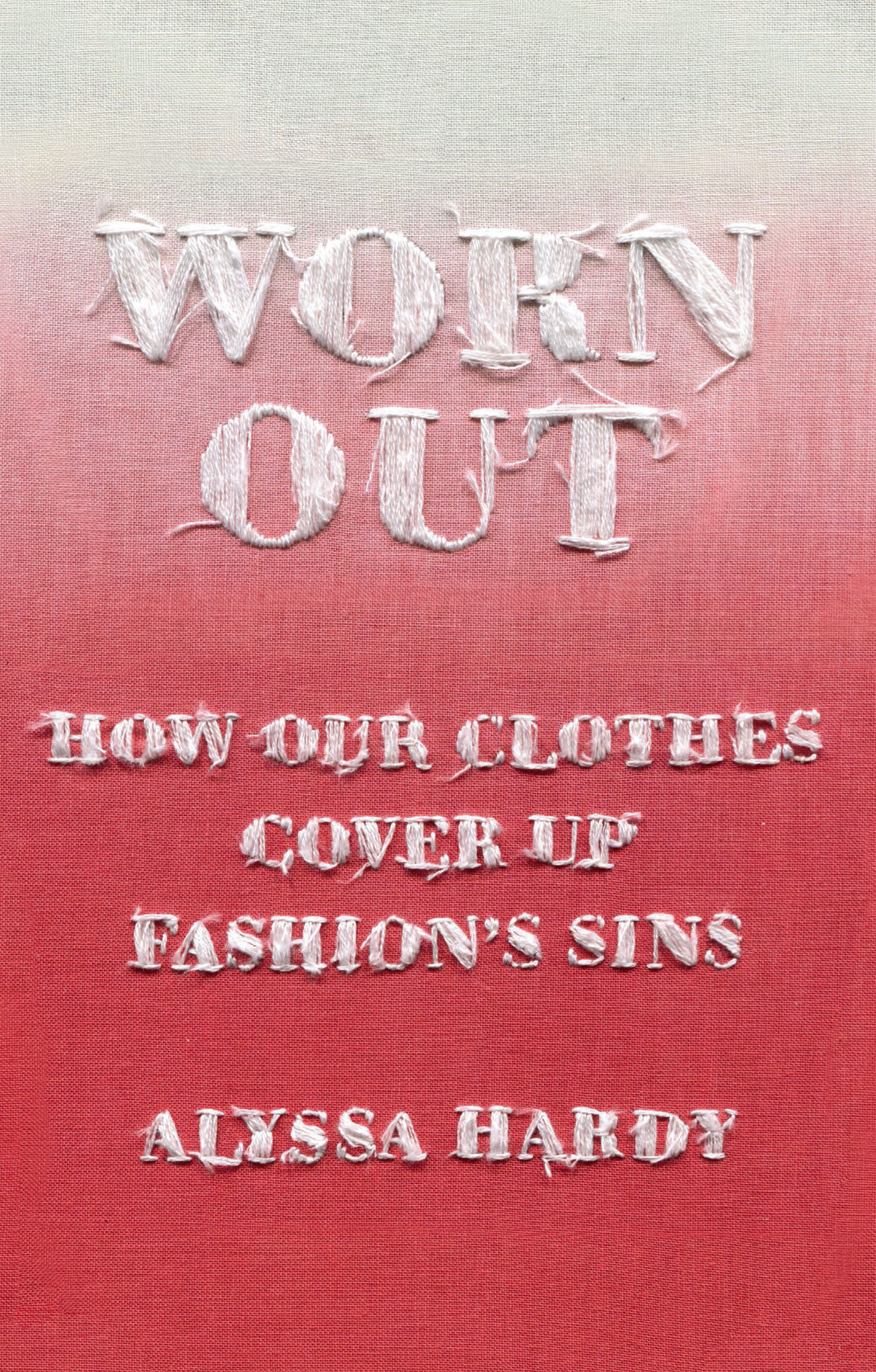

Worn Out

How Our Clothes Cover Up Fashions Sins

Alyssa Hardy

To every worker who brings style into this world. And to my mother, who taught me that every woman deserves to be heard.

Contents

Introduction

WHEN YOU PICKED UP THIS BOOK, YOU PROBABLY WERENT anticipating a love story. I want to make it clear, though, thats what this is. I will spend a lot of time telling you that fashion is a secretive and problematic industry, that its opulence is built on horrific labor and marketing practices often perpetuated by those of us who work inside it. And thats all true. At the same time, though, fashion is the glue that pulls us all together. Its the buzz that makes you feel confident when you put on your favorite pair of jeans for a night out with your friends. Its the warmth you feel when a stranger tells you they like your top. Its the pit in your stomach when you pull your late grandmothers necklace out of your jewelry box. Its the way we preserve traditions and honor our past. Its the love affair that has framed my entire adult life.

I want to start with some familiar territory: the inescapable experience lived by any human alive today, the COVID-19 pandemic. In the early weeks, after the crisis hit most major cities around the world, those of us lucky enough to be locked up inside our houses shifted our focus from the trauma on our news screens and in our social media feeds to fashion. It wasnt just me, a person whose life revolves around the industry; it was everyone. At first, those working from home embraced the switch from slacks to sweatpants, joking about dirty pajamas and tight jeans that never saw the light of day. Our jewelry remained where wed tossed it before the world crashed around us and our high heels were stashed in the back of our closets, replaced by UGG boots and Birkenstocks. We embraced a new type of fashion normal that let go of acceptable work attire and instead prioritized our comfort when we needed it most.

There was a lot of talk about consumption, too. In the pandemic before-times, I think most people understood that we have too many clothes, and that somehow it is bad for the environment. When the future of the world felt so uncertain, it suddenly seemed silly to have all these things growing stale in our closets, and that made many of us reevaluate our previous fashion choices. Yet need versus want only went so far to curb our shopping habits. By late summer 2020, sales for sweatpants and loungewear skyrocketed by around 600 percent. Some fast fashion brands, like Boohoo and Fashion Nova, had their best profits of all time that year. What we had in our drawers for a lazy Saturday or a night alone after work was no longer cutting it every single day of our lives, so we looked for more. Matching sweatpants sets, colorful slippers, and nap dresses were marketed to us on social media shopping platforms, and we bought in.

Those without the privilege of working from home in sweatpants all day contributed to our shift in fashion too. After mask mandates took hold in April of that year, you could find a floral face mask to match your summer dress, a sporty one for your run, or even a luxury style with a recognizable logo like the Chanel double-C print. Some workers wore custom ones given to them by their employermy dad, for example, worked at the post office warehouse and had a USPS-branded face mask he wore every day.

You know all of this, though. Because through our style choices that year, we had another collective experience inflicted on us. Fashion and style were our happy commonplace. We could joke about not knowing how to dress or share tips about mask-wearing and it was a thread we followed together while we dealt with heavier stuff individually.

But this story of a style evolution that none of us asked for, swept up into think pieces by fashion magazines, new loungewear collections by brands, and Instagram stories from influencers, did leave something out. Behind all of these sudden changes to wardrobes was a huge problem. In the garment factories, where workers had to switch their flow to make masks and sweatpants, there was a wage crisis. Many brands, particularly in the fast fashion sector, suddenly canceled full collections that they had ordered their manufacturers to produce, leaving workers with no pay for work they had already done or, in some cases, were still doing. Others were lauded as heroes when they switched production to making PPE like hospital gowns and masks (which were in desperately short supply) but werent even providing that protection to the workers who were making them. Many of them ended up sick or dead from the virus.

In the Los Angeles Apparel factory, owned by disgraced American Apparel founder Dov CharneyIll get to him later toothree hundred garment workers tested positive for the coronavirus in June and three died within the following weeks. The health department eventually inspected the factory and swiftly shut it down for, as a press release noted, flagrant violations of mandatory public health infection control orders and failure to cooperate with DPHs investigation of a reported COVID-19 outbreak. In other factories in Los Angeles, workers were being paid a piece rate for the masks, sometimes making only 5 cents for each one, or around $180 a week for full-time work. Notably, 80 percent of these workers are women.

Around the world, garment workers who were making masks and sweatpants at similarly low rates, often even lower, were being swept up into global crisis. In Myanmar, workers who made a vast majority of the PPE Zara donated to patients and healthcare workers in Spain were on the front lines when the military staged a coup of their government. The womenled unions left work to protest the takeover and had to beg brands to continue to employ them while they did. In India, where garment work is one of the top employment opportunities, people could not afford to stay home when the crisis hit. They got sick, and many of them died.

While this may sound like a huge oversight by government and the fashion brands, for the workers it was business as usual. Many of them never expected to be treated with compassion or dignity during this time, but they showed up and did the work anyway. Its something I wish could have been put as a disclaimer in every single mask trend story or think piece I wrote in those months. Something like: This mask may protect youbut no guarantees for the person who made it.

To me, the way we treated fashion during the pandemic was emblematic of how its always been looked at, how I used to look at it. Its something for us to consume en masse, it makes us feel good, it sparkles. Its impact on people is never discussed, just hidden in plain sight, and we all willfully look away. Even when its supposed to protect you, it might have been hurting someone else.

This feeling came to a head in late spring 2021, when mask mandates began to be lifted in the United States. One Sunday afternoon, I walked into a bodega to buy a water. It was warmer than I anticipated, and I was wearing a blazer over my T-shirt and jeans paired with heeled boots that had been sitting sad and alone in my closet for the last fourteen months. I was on my way to visit a garment factory in Midtown Manhattan with Senator Kirsten Gillibrand. (Youre supposed to wear a blazer when you meet a senator, right?) The owner of the bodega still had plastic barriers up around the cash register to protect him from the customers. Taped all over it were different types of face masks: KN95s, a cloth one that read I Love NY, along with others that had leopard or camo print, all selling for around $5. In the moment, I didnt think anything of it. By this point, the days of mask shortages were long over; now masks were being sold everywhere from bodegas to plant shops. They were inescapable.