ABOUT THE AUTHOR

A NDREW B ROOKS is a lecturer in development geography at Kings College London. His research examines connections between spaces of production and places of consumption, and particularly the geographies of economic and social change in Africa. Fieldwork has taken him to India, Papua New Guinea and across Africa. Research in Africa has included extensive investigations of markets and politics in Malawi and Mozambique as well as Chinese investment in Zambia.

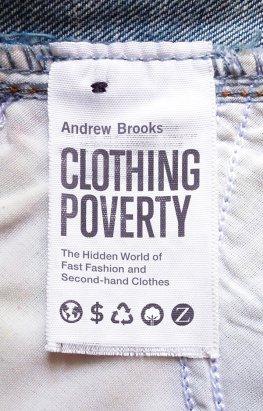

CLOTHING POVERTY

The hidden world of fast fashion

and second-hand clothes

ANDREW BROOKS

Zed Books | LONDON

Clothing Poverty: The Hidden World of Fast Fashion and Second-hand Clothes was first published in 2015 by Zed Books Ltd, 7 Cynthia Street, London N1 9JF, UK

www.zedbooks.co.uk

Copyright Andrew Brooks 2015

The right of Andrew Brooks to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

Designed and typeset in Monotype Bulmer by illuminati, Grosmont

Index by John Barker

Cover designed by www.alice-marwick.co.uk

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of Zed Books Ltd.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781783600687 hb

ISBN 9781783600670 pb

ISBN 9781783600700 pdf

ISBN 9781783600694 epub

ISBN 9781783600717 mobi

Contents

There was no single moment or event that led me to write an accessible book on globalization and the clothing trade. The idea developed as I studied, worked and researched in different places, from my small office in London to sprawling markets in southern Africa, until it had become something that I felt would not only be interesting and important to write, but also something I knew I had to do. Throughout time spent variously as a geography undergraduate and later a lecturer at Kings College London, a volunteer in Papua New Guinea, an international development worker, a graduate student at Royal Holloway, a field researcher in Zambia and Mozambique and elsewhere around the world, there have always been friends, family and colleagues who have offered encouragement, support and guidance, for which I am very grateful. Kim Walker and others at Zed Books have also always been very helpful. Any errors are of course my sole responsibility.

For me, global poverty and inequality have always stood out as the defining issues of our time, yet it is frustrating how often work on these topics falls short of offering answers, a compelling argument or an engaging narrative. We have to work rigorously to understand how the world has changed and developed, yet in doing so try hard to make the analysis interesting and clear, as well as authoritative. My hope is that this book goes some way to bridging between the real experiences of the poor and the sometimes dry and introverted academic community, and tells a story of uneven development that is interesting for a broad audience by discussing the hidden world of clothing through diverse and colourful examples, while maintaining a critical perspective. The work that follows, therefore, is one that draws on my experiences and knowledge and tries to deliver a message and discussion that others may learn from. In the pursuit of this goal, special thanks must go to David Simon and Alex Loftus for their help and support, which inspired me to develop the project.

Everyone knows that most Africans are poor. Life expectancy is low, education is basic, food is simple, and clothes are few. Curving around the south-east coast of the continent, Mozambique has a typically African economy. Many Mozambicans are dependent on subsistence agriculture or low-value exports such as cashew nuts, cotton and Indian Ocean shrimps. Beneath the shrimps and the warm waters are rich natural gas reserves, which could fuel development, but these resources are more likely to be stolen or squandered overseas, as recent economic growth has contributed to rising inequality rather than a reduction in poverty. Like much of Africa, Mozambiques national budget is dependent on support from overseas aid, and the liberalized economy is wide open to both exports and imports. The capital, Maputo, is an important regional port 30 miles from South Africa. Tree-lined avenues, a legacy of Portuguese colonialism, stretch out from the city centre towards poorer neighbourhoods. At the end of one of these avenues on the edge of the downtown is the sprawling and bustling Mercado do Xipamanine Xipamanine market.

On any weekday morning the entrance to Xipamanine market is crowded; minivans clog the narrow approach road and hawkers circle, touting cheap Chinese manufactured goods such as plastic clothes pegs, polyester socks and pressed steel cutlery. Entering the market one passes through narrow alleys, between market stalls selling a mix of local food and international products: coconuts, mangoes, pineapples, fresh fish, suitcases, school stationary and stereos pumping out the latest R&B beats from New York and Los Angeles. It is lively and vibrant, rich in all sorts of smells and muddy under foot. Moving further into the market you begin to encounter noisy traders negotiating the sale of cheap, low-quality, imported new clothing. There are soccer shirts with English Premier League logos or Mozambican flags, brightly coloured floral ladies tops, and the novelty of Barack Obama-branded belt buckles. Beyond these new clothing vendors is the heart of the market, and here we find Marios used-clothing stall.

Mario is in his early thirties; he migrated to Maputo from rural Inhambane province in search of work. He makes a living selling second-hand jeans imported from North America and Europe. Six days a week he comes to his simple wooden market stall and sets out his stock. The jeans are carefully arranged according to quality. Pristine pairs of Calvin Kleins and Levis hang on display on improvised coat-hangers, while low-value torn and soiled denim is heaped on the ground on polythene sacks. Mario buys mixed consignments of used jeans shipped to Mozambique from rich countries. All of the jeans have their own unique and unknown stories; maybe they were outgrown by an American teenager, discarded by a fashion-conscious Canadian student, or worn out by a British construction worker. At one time the jeans have all been bought, owned and worn by someone in North America or Europe, and then recycled and ended up far away in an African marketplace. Some jeans show the marks of their previous lives; there are rips, scuffs and stains, and scraps of paper in the pockets. The dirtiest and most torn jeans wont be sold, and if Mario ends up with too many low-quality pairs he will lose money.

Traders in Xipamanine market are familiar with Western popular culture and work hard to identify clothes which will appeal to customers who are poor but nevertheless caught up in the currents of global fashion. Mario enjoys American hip hop and English football. He knows all the results and soccer gossip, and what tracks are in vogue with Mozambican teens. Although Mario recognizes Beyonc songs, Manchester United players, and what styles of denim sell well, he does not know where the jeans come from or how they get to Maputo. Globally the used-clothing trade is a large and growing sector, but here in this cramped market business is usually slow during the long, stiflingly hot afternoons. Between sales Mario is preoccupied with more pressing matters than thinking about how second-hand jeans from the West end up on his stall. He faces the persistent dilemma of deciding whether to take a risk and spend more money on another package of used denim, save funds to pay for further education so he can try and find a formal job, or use the cash to provide for his young family. Like the other thousand or so second-hand traders in Xipamanine market, Mario has a precarious small business; while he is able to provide for his household, he still faces the constant demand for basic necessities at home. Ultimately he cannot escape poverty through selling second-hand clothes. For him this is his only means of making a living, and he does not dwell on the origins and impacts of the second-hand clothing trade.

Next page